From

Nautilus Magazine, this article takes a look at efforts to make emotionally intelligent robots. Researchers currently limit any efforts to teach robots to "feel" emotions to six emotions "

anger, sadness, disgust, happiness, fear, and 'neutral.'"

One of the issues I see with this EVER happening is that human emotions are body-based (unless we create robots with biological bodies).

Antonio Damasio is the researcher who makes this most clear in his several books. In our daily usage, feelings and emotions are often used interchangeably.

But for neuroscience, emotions are more or less the complex reactions the body has to certain stimuli. When we are afraid of something, our hearts begin to race, our mouths become dry, our skin turns pale and our muscles contract. This emotional reaction occurs automatically and unconsciously. Feelings occur after we become aware in our brain of such physical changes; only then do we experience the feeling of fear. [Damasio, Scientific American interview, Feeling Our Emotions; March, 2005]

Emotions are what we experience in the body, which our brain then interprets into

feelings. Robots do not have a

peripheral nervous system (PNS) as we do, they can not have an

enteric nervous system (ENS) [see

here also] as we do, and they can not have an

autonomic nervous system (ANS) as we do.

While robots might be understood to have "unconscious" processes much like our ANS, those processes are not "embodied" as ours are and, therefore, cannot be a part of the emotion system in the same way a rapid heartbeat can generate feelings of anxiety (the emotion is the combination of rapid heartbeat, shallow breathing, and stomach butterflies, which our brain then interprets based on context as either anxiety or excitement).

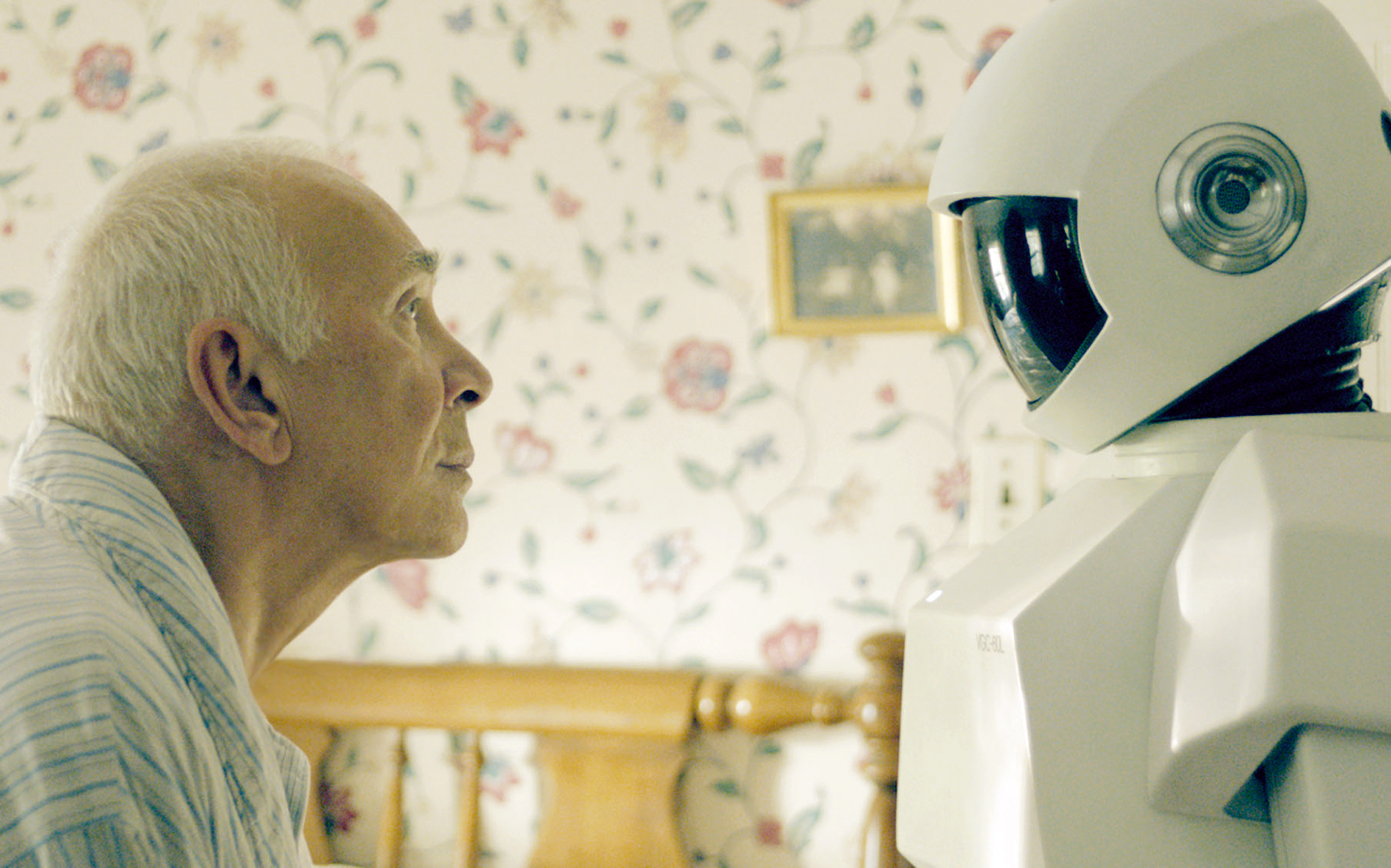

Anyway, all of this to suggest I have serious doubts about robots and emotions. For an interesting film take on this, see

Robot and Frank (image at the top is from the film).

How long until a robot cries?

By Neil Savage

Illustrations by John Hendrix

When Angelica Lim bakes macaroons, she has her own kitchen helper, Naoki. Her assistant is only good at the repetitive tasks, like sifting flour, but he makes the job more fun. Naoki is very cute, just under two feet tall. He’s white, mostly, with blue highlights, and has speakers where his ears should be. The little round circle of a mouth that gives him a surprised expression is actually a camera, and his eyes are infrared receivers and transmitters.

“I just love robots,” says Lim, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Intelligent Science and Technology at Kyoto University in Japan. She uses the robot from Aldebaran Robotics in Paris to explore how robots might express emotions and interact with people. When Lim plays the flute, Naoki (the Japanese characters of his name translate roughly to “more than a machine”) accompanies her on the theremin or the egg shaker. She believes it won’t be too many years before robotic companions share our homes and our lives.

Of course Naoki doesn’t get the jokes, or enjoy the music, or feel his mouth watering over the cookies. Though we might refer to a person-shaped robot as “him,” we know it’s just a collection of metal parts and circuit boards. When we yell at Siri or swear at our desktop, we don’t really believe they’re being deliberately obtuse. And they’re certainly not going to react to our frustration; machines don’t understand what we feel.

At least that’s what we’d like to believe. Having feelings, we usually assume, and the ability to read emotions in others, are human traits. We don’t expect machines to know what we’re thinking or react to our moods. And we feel superior to them because we emote and they don’t. No matter how quick and logical they are, sensitive humans win and prevail over machines: emotional David Bowman beats calculative HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey, and desperate Sarah Connor triumphs over the ultimate killing machine in The Terminator. From Dr. McCoy condemning the unemotional Spock as a “green-blooded inhuman” in Star Trek to moral reasoning that revolves around the unemotionality of criminals, we hold our emotions at the core of our identity.

Special and indecipherable, except by us—our whims and fancies are what makes us human. But we may be wrong in our thinking. Far from being some inexplicable, ethereal quality of humanity, emotions may be nothing more than an autonomic response to changes in our environment, software programmed into our biological hardware by evolution as a survival response.

Joseph LeDoux, a neuroscientist at New York University’s Center for Neural Science, describes emotion in terms of “survival circuits” that exist in all living things. An organism, as simple as an amoeba or as complex as a person, reacts to an environmental stimulus in a way that makes it more likely to survive and reproduce. The stimulus flip switches on survival circuits which prompt behaviors that enhance survival. Neurons firing in a particular pattern might trigger the brain to order the release of adrenaline, which makes the heart beat faster, priming an animal to fight or flee from danger. That physical state, LeDoux says, is an emotion.

Melissa Sturge-Apple, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Rochester, agrees that emotions have something to do with our survival. “They’re kind of a response to environmental cues, and that organizes your actions,” she says. “If you’re fearful, you might run away. If you get pleasure from eating something, you might eat more of it. You do things that facilitate your survival.” And key among the human’s survival tool kit is communication—something emotions help facilitate, through the use of empathy.

By this reasoning, every living thing interested in survival emotes in some form, though perhaps not in quite the same way as humans. Certainly any pet owner will tell you that dogs experience emotions. The things we call feelings are our conscious interpretation and description of those emotional states, LeDoux argues. Other types of feelings, such as guilt, envy, or pride, are what he calls “higher order or social emotions.”

We are also beginning to understand that the mechanics of how we express emotion are deeply tied into the emotion itself. Oftentimes, they determine what we are feeling. Smiling makes you happier, even if it’s because Botox has frozen your face into an unholy imitation, author Eric Finzi says in his recent book The Face of Emotion. Conversely, people whose facial muscles are immobilized by Botox injections can’t mirror other people’s expressions, and have less empathy. No mechanics, no emotion, it seems.

But if our emotional states are indeed mechanical, they can be detected and measured, which is what scientists in the field of affective computing are working on. They’re hoping to enable machines to read a person’s affect the same way we display and detect our feelings—by capturing clues from our voices, our faces, even the way we walk. Computer scientists and psychologists are training machines to recognize and respond to human emotion. They’re trying to break down feelings into quantifiable properties, with mechanisms that can be described, and quantities that can be measured and analyzed. They’re working on algorithms that will alert therapists when a patient is trying to hide his real feelings and computers that can sense and respond to our moods. Some are breaking down emotion into mathematical formalism that can be programmed into robots, because machines motivated by fear or joy or desire might make better decisions and accomplish their goals more efficiently.

Wendi Heinzelman, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Rochester and a collaborator of Sturge-Apple, is developing an algorithm to detect emotion based on the vocal qualities of a speaker. Heinzelman feeds a computer speech samples recorded by actors attempting to convey particular feelings, and tells the computer which clips sound happy, sad, angry, and so on. The computer measures the pitch, energy and loudness of the recordings, as well as the fluctuations in energy and pitch from one moment to the next. More fluctuations can suggest a more active emotional state, such as happiness or fear. The computer also tracks what are known as formants, a band of fundamental frequencies that are affected by the shape of the vocal tract. If your throat tightens because you’re angry, it alters your voice—and the computer can measure that. With these data, it can run a statistical analysis to figure out what distinguishes one emotion from another.

Neal Lathia, a post-doctoral research associate in the computer laboratory at the University of Cambridge, in England, is working on EmotionSense, an app for Android phones which listens to human speech and ferrets out its emotional content in a similar way. For instance, it may decide that there’s a 90 percent chance the speaker is happy and report that, “from a purely statistical perspective, you sound most like this actor who had claimed he was expressing happiness,” Lathia explains.

Like Lathia and Heinzelman, Lim thinks there are certain identifiable qualities to emotional expression, and that when we detect those qualities in the behavior of an animal or the sound of a song, we ascribe the associated emotion to it. “I’m more interested in how we detect emotions in other things, like music or a little puppy jumping around,” she says. Why, for instance, should we ascribe sadness to a particular piece of music? “There’s nothing intrinsically sad about this music, so how do we extract sadness from that?” She uses four parameters: speed, intensity, regularity, and extent—whether something is small or large, soft or loud. Angry speech might be rapid, loud, rough and broken. So might an angry piece of music. Someone who’s walking at a moderate pace using regular strides and not stomping around might be seen as content, whereas a person slowly shuffling, with small steps and an irregular stride, might be displaying that they’re sad. Lim’s hypothesis, as yet untested, is that mothers convey emotion to their babies through those qualities of speed, intensity, regularity, and extent in their speech and facial expressions—so humans learn to think of them as markers of emotion.

Currently, researchers work with a limited set of emotions in order to make it easier for the computer to distinguish one from another, and because the difference between joy and glee or anger and contempt is subtle and complex. “The more emotions you get, the harder it is to do this because they’re so similar,” says Heinzelman, who focuses on six emotions: anger, sadness, disgust, happiness, fear, and “neutral.” And for therapists looking for a way to measure patients’ general state of mind, grouping them into these general categories may be all that’s necessary, she says.

Voice, of course, is not the only way people convey their emotional states. Maja Pantic, professor of affective and behavioral computing and leader of Imperial College London’s Intelligent Behavior and Understanding Group, uses computer vision to capture facial expressions and analyze what they tell about a person’s feelings. Her system tracks various facial movements such as the lifting or lowering of an eyebrow and movements in the muscles around the mouth or the eyes. It can tell the difference between a genuine and a polite smile based on how quickly the smile forms and how long it lasts. Pantic has identified 45 different facial actions, of which her computer can recognize 30 about 80 percent of the time. The rest are obscured by the limitations of the computer’s two-dimensional vision and other obstacles. Actions such as movements in a different direction, jaw clenching and teeth grinding—which may indicate feeling—are hard for it to recognize. Most emotion identification systems work pretty well in a lab. In the real world with imperfect conditions, their accuracy is still low, but it’s getting better. “I believe in a couple of years, probably five years, we will have systems that can do analysis in the wild and also learn new patterns in an unsupervised way,” Pantic says.

With emotions reduced to their components, recorded, and analyzed, it becomes possible to input them into machines. The value of this project might seem simple: the resulting robots will have richer, more interesting and more fun interactions with humans. Lim hopes that, in the future, how Naoki moves and how it plays the theramin will allow it to express its emotional states.

But there are also deeper reasons why engineers are interested in emotional robots. If emotions help living things survive, will they do the same for robots? An intelligent agent—a robot or a piece of software—that could experience emotions in response to its environment could make quick decisions, like a human dropping everything and fleeing when he sees his house is on fire. “Emotions focus your attention,” says Mehdi Dastani, a professor of computer science at the University of Utrecht, in the Netherlands. “Your focus gets changed from what you’re working on to a much more important goal, like saving your life.”

Dastani is providing intelligent agents with what he calls a “logic of emotion,” a formalized description of 22 different emotional states such as pity, gloating, resentment, pride, admiration, gratitude, and others. A robot can use them, he explains, to evaluate progress it’s making toward a goal. An unemotional robot, directed to go from Point A to Point B, might hit an obstacle in its path and simply keep banging into it. An intelligent agent equipped with emotion might feel sad at its lack of progress, and eventually give up and go do something else. If the robot feels happy, that means it’s getting closer to its goal, and it should stay the course. But if it’s frustrated, it may have to try another tack. The robot’s emotions offer a kind of problem-solving strategy computer scientists call a heuristic, which is the ability to discover and learn things for themselves—like humans do. “Emotion is a kind of evolutionarily established heuristic mechanism that intervenes in rational decision-making, to make decision-making more efficient and effective,” Dastani says.

But could a machine actually have emotions? Arvid Kappas, a professor of psychology who runs the Emotion, Cognition, and Social Context group at Jacobs University in Bremen, Germany, believes that it comes back to the definition of emotion. By some definitions, even a human baby, which operates mostly on instinct and doesn’t have the cognitive capacity to understand or describe its feelings, might be said to have no emotions. By other definitions, the trait exists in all sorts of animals, with most people willing to ascribe feelings to creatures that closely resemble humans. So does he believe a computer could be emotional? “As emotional as a crocodile, sure. As emotional as a fish, yes. As emotional as a dog, I can see that.”

But would robots that felt, feel the same way we do? “They would probably be machine emotions and not human emotions, because they have machine bodies,” says Kappas. Emotions are tied into our sense of ourselves as physical beings. A robot might have such a sense, but it would be of a very different self, with no heart and a battery meter instead of a stomach. An android in power-saving mode may, in fact, dream of electric sheep. And that starts to raise ethical questions. What responsibility does a human have when the Roomba begs not to let its battery die? What do you say to Robot Charlie when the Charlie S6 comes out, and you want to send the old model to the recycling plant?

“It really is important, if humans are going to be interacting with robots, to think about whether robots could be feeling and under what conditions,” says Bruce MacLennan, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, who will be presenting a paper on the ethical treatment of future robots at the International Association for Computing and Philosophy this summer. MacLennan feels that this isn’t just a philosophical question, but one that can be tackled scientifically. He proposes trying to break emotions down into what he calls “protophenomena,” the tiniest units of the physical effects that lead to emotion. “Protophenomena are so small that they’re not normally something a person would be aware of as part of their conscious experience,” he says. There should be some basic physical quantities that science can measure and, therefore, reproduce—in machines.

“I think anything that’s going to be able to make the kinds of decisions we want a human- scale android to make, they’re going to inevitably have consciousness,” MacClennan says. And, LeDoux argues, since human consciousness drives our experience of emotion, that could give rise to robots actually experiencing feelings.

It will probably be many decades before we’re forced to confront questions of whether robots can have emotions comparable to humans, says MacLennan. “I don’t think they’re immediate questions that need to be answered, but they do illuminate our understanding of ourselves, so they’re good to address.” Co-existing with emotional robots, he argues, could have as profound an effect as one civilization meeting another, or as humanity making contact with extraterrestrial intelligence. We would be forced to face the question of whether there’s anything so special about our feelings, and if not, whether there’s anything special about us at all. “It would maybe focus us more on what makes humans human,” he says, “to be confronted by something that is so like us in some ways, but in other ways is totally alien.”

Neil Savage is a freelance science and technology writer in Massachusetts. His story for Nature about artificial tongues won an award from the American Society of Journalists and Authors. He has also written about companion robots for the elderly for Nature, electronic spider silk for IEEE Spectrum, and bionic limbs for Discover. To see his works, visit www.neilsavage.com.

Robert Wright

Robert Wright