Somehow, while I was down the

complex adaptive systems rabbit hole, I stumbled across another new term, causal pluralism. A quick and easy definition comes from

Peter Godfrey-Smith (Harvard University):

Causal pluralism is the view that causation is not a single kind of relation or connection between things in the world. Instead, the apparently simple and univocal term "cause" is seen as masking an underlying diversity.

Leen De Vreese (Centre for Logic and Philosophy of Science; Ghent University, Belgium) argues that the field is still relatively new (as of early 2007), but the term “causal pluralism” already has accrued a variety of meanings, which he feels leads to confusion. In his paper,

Disentangling Causal Pluralism, he tries to sort the threads of pluralistic approaches to causation and to identify the different perspectives held by their adherents.

I wonder if he sees the irony in trying to identify the individual ideas and perspectives that constitute the pluralist origins of causal pluralism?

Full Citation:

De Vreese, L, Weber, E. (2008). Disentangling Causal Pluralism. Robrecht Vanderbeeken, (ed.), Worldviews, Science, and Us: Studies of Analytical Metaphysics. A Selection of Topics From a Methodological Perspective. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Company.

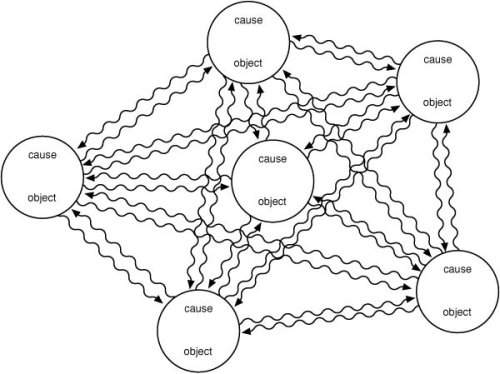

De Vreese identifies three basic kinds of causal pluralism:

- conceptual causal pluralism

- metaphysical causal pluralism

- epistemological-methodological causal pluralism

Each of these positions has an opposite stance in the monistic causation camp.

However, his primary agenda in the paper is to reduce the (perceived) confusion in the field of causal

pluralism by identifying the perspectives being taken in relation to metaphysical causal pluralism. In essence, are there metaphysical reasons to accept causal pluralism, or is causal pluralism only a conceptual matter

He proposes three "central metaphysical questions" about causation to achieve this goal.

- Firstly, is causation a realistic notion, or is it a mental construct?

- Secondly, does causation only occur as a real relation at the fundamental level of reality, or does it also occur as a real relation between objects at higher levels of reality?

- And lastly, does causation consist in a single empirical relation, or does it consist in diverse empirical relations deserving the label “causal”?

In answering these questions, he proposes four types of metaphysical perspectives regarding causation:

- metaphysical causal constructivism

- strong metaphysical causal pluralism

- weak metaphysical causal pluralism

- metaphysical causal monism

He concludes his paper by making a clear distinction between conceptual and metaphysical causal pluralism from a third variation on causal pluralism, which he terms "

epistemological-methodological causal pluralism." He is referring to "

the importance of a pluralistic view on causation for our scientific knowledge in general on the one hand, and for assembling causal knowledge in specific domains of science on the other hand."

While he maintains that an epistemological-methodological approach to causation is still intimately related to conceptual and metaphysical causal pluralism, he feels it's still important to value this line of approach as different from the others, maintaining that "

certain questions become utterly important for the sake of our knowledge."

That is one view of causal pluralism, but there are as many variations as there are authors, or at least that is how it seems to a new reader in the field.

In an article more specifically relevant to my work, Julian Reiss (Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands) published

Causation in the Social Sciences: Evidence, Inference, and Purpose in

Philosophy of the Social Sciences (2009).

Full Citation:

Reiss, J. (2009, Mar). Causation in the Social Sciences: Evidence, Inference, and Purpose. Philosophy of the Social Sciences, Volume 39(1); 20-40. doi: 10.1177/0048393108328150

Abstract:

All univocal analyses of causation face counterexamples. An attractive response to this situation is to become a pluralist about causal relationships. “Causal pluralism” is itself, however, a pluralistic notion. In this article, I argue in favor of pluralism about concepts of cause in the social sciences. The article will show that evidence for, inference from, and the purpose of causal claims are very closely linked.

This is definitely worth the read.

In an oft-cited paper, Christopher Hitchcock's

Of Humean Bondage, he offers a classification scheme for the various forms of causal pluralism. He clarifies up front that he is interested in a pluralism of causation, not a pluralism of causes (which he claims all philosophers already accept). This paper relies more on classical logic arguments in assigning causation, but it is still useful.

Finally,

Cognitive Psychology (2010) published

Causal–explanatory pluralism: How intentions, functions, and mechanisms influence causal ascriptions by Tania Lombrozo, for which this is the abstract:

Both philosophers and psychologists have argued for the existence of distinct kinds of explanations, including teleological explanations that cite functions or goals, and mechanistic explanations that cite causal mechanisms. Theories of causation, in contrast, have generally been unitary, with dominant theories focusing either on counterfactual dependence or on physical connections. This paper argues that both approaches to causation are psychologically real, with different modes of explanation promoting judgments more or less consistent with each approach. Two sets of experiments isolate the contributions of counterfactual dependence and physical connections in causal ascriptions involving events with people, artifacts, or biological traits, and manipulate whether the events are construed teleologically or mechanistically. The findings suggest that when events are construed teleologically, causal ascriptions are sensitive to counterfactual dependence and relatively insensitive to the presence of physical connections, but when events are construed mechanistically, causal ascriptions are sensitive to both counterfactual dependence and physical connections. The conclusion introduces an account of causation, an ‘‘exportable dependence theory,” that provides a way to understand the contributions of physical connections and teleology in terms of the functions of causal ascriptions.

It's probably indicative of my geekiness that I am looking forward to reading this one.

Here are a few other papers, all of which are freely available online.

iStockphoto.com

iStockphoto.com