James R Hamblin's review (This Is Your Brain on Gluten) in The Atlantic (where he is a senior editor) of David Perlmutter's Grain Brain: The Surprising Truth about Wheat, Carbs, and Sugar--Your Brain's Silent Killers has generated a lot of backlash against Perlmutter's claims in the book.

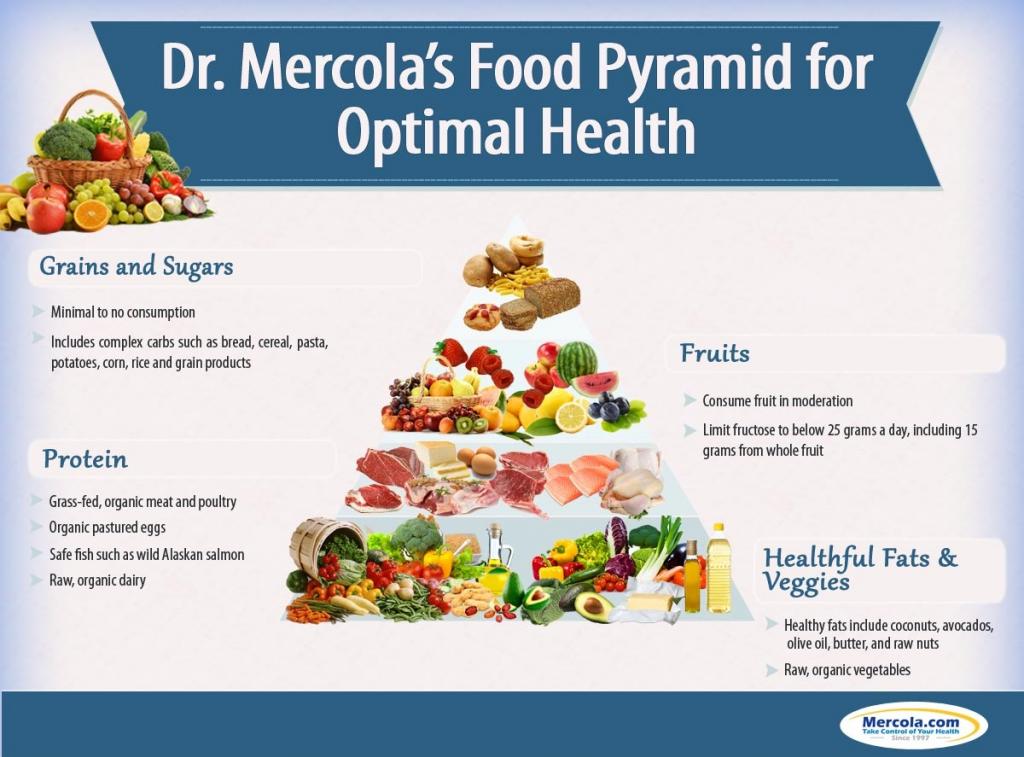

Perlmutter makes a few claims that are nearly opposite of what mainstream nutrition teaches us is true (as in the 1992 USDA Food Pyramid above):

- Gluten is poison, and we should not eat any wheat (or rye, barley, and several other grains)

- Sugars, especially fructose, are also poisons and we should seriously restrict their intake

- LDL cholesterol is only a problem when it becomes oxidized (which occurs with carbohydrate consumption)

- Cholesterol is good for us - there is no such thing as too much

- If we adhere to these four points, we can prevent a LOT of neurodegenerative diseases

There is also a brief video of Perlmutter outlining his inverse food pyramid:

Hamblin's review in The Atlantic was highly skeptical in tone and content - but while he tried to refute several of Perlmutter's central ideas, the research he sites supports the premise, although it is not nearly as conclusive as Perlmutter presents it.

I read the book with an eye for the most dangerous claim. What stuck out to me was Perlmutter’s case for cholesterol. He basically says that we can’t have too much.The reality about cholesterol is not quite as clear-cut as Perlmutter argues, but it is true that there is only about a 5-15% correlation between dietary intake of cholesterol and blood levels of cholesterol. From Wikipedia:

“Nothing could be further from the truth than the myth that if we lower our cholesterol levels, we might have a chance of living longer and healthier lives,” Perlmutter writes . He recommends disowning the notion that LDL is bad cholesterol and HDL is good cholesterol; rather, both are generally good. LDL is only bad when it is oxidized, and it only becomes so in the presence of the sort of oxidative stress brought about by carbs and gluten. Avoid those, and cholesterol is innocuous.

Beyond that, Perlmutter says that cholesterol-lowering statin medicines like Lipitor, which are prescribed for a quarter of Americans over 40, should actually be vehemently avoided. Cholesterol is necessary for the brain in high levels, he says, and lowering it is contributing to dementia.

I took this to Katz, too.

“Is there a weight of evidence that says we can totally ignore both dietary cholesterol and LDL? Absolutely not,” he said. “You can legitimately say we’re starting to rethink some things, but ignoring LDL could absolutely result in heart attacks and strokes. Perlmutter is way ahead of any justifiable conclusion.”

The medical community’s understanding of the danger of cholesterol is changing. Many cardiologists are starting to think that independent of other considerations, the level of LDL in our blood may not be as important as it previously seemed. In November, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology released new guidelines that redefined the use of statins. While they continue to recommend that people at high risk for heart disease and people with LDL levels above 189 take a statin, the long-standing goal of lowering one’s LDL level to 70 is no longer deemed worthwhile to monitor.

Most ingested cholesterol is esterified, and esterified cholesterol is poorly absorbed. The body also compensates for any absorption of additional cholesterol by reducing cholesterol synthesis.[9] For these reasons, cholesterol intake in food has little, if any, effect on total body cholesterol content or concentrations of cholesterol in the blood.The primary reason for this, as Perlmutter describes, is that the body would much prefer to use dietary cholesterol for the many cellular and hormonal processes based on its metabolism (most notably as an essential structural component of cell membranes and necessary to establish proper membrane permeability and fluidity, as well as it's role as the building block of sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen). Making cholesterol from sugars and saturated fats is an energy demanding process. Importantly, cholesterol is NOT really a fat - it is technically a sterol, a modified steroid.

LDL cholesterol is the evil cause of heart disease and a host of other diseases according to the medical mainstream. However, research from a few years back indicates that low cholesterol may actually cause more non-coronary deaths than high cholesterol. Moreover, as Perlmutter argues, statins that lower cholesterol compromise brain function because they don't only stop the liver from making cholesterol, they also stop the brain from doing so.

Yeon-Kyun Shin, a biophysics professor in the department of biochemistry, biophysics and molecular biology, says the results of his study show that drugs that inhibit the liver from making cholesterol may also keep the brain from making cholesterol, which is vital to efficient brain function.

"If you deprive cholesterol from the brain, then you directly affect the machinery that triggers the release of neurotransmitters," said Shin. "Neurotransmitters affect the data-processing and memory functions. In other words -- how smart you are and how well you remember things."

Another fallacy around cholesterol and health is that fat is the primary source of increased circulating LDL cholesterol. Fructose is a much larger issue - as soon as fructose is ingested it goes straight to the liver where it is converted into triglycerides to be stored as fat. Considering the enormous levels of high-fructose corn syrup consumed by the Western world, it's no wonder obesity is such a rampant problem.

The effects of different dietary sugars, with or without exogenously induced hyperinsulinemia, on rat plasma triglyceride kinetics have been studied. Glucose, sucrose, or fructose were supplied as 10% drinking solutions. The sugar-supplemented groups were each divided into subgroups, one receiving 6 U of insulin per day for 2 wk from intraperitoneally implanted minipumps and the other receiving none. The same degree of hyperglycemia and of endogenous hyperinsulinemia was seen in each sugar-supplemented group. Infusing exogenous insulin restored normoglycemia and produced more pronounced but equal hyperinsulinemia in each subgroup. In those rats that received no exogenous insulin, triglyceride production increased 18% in the sucrose-supplemented group and 20% in the fructose supplemented subgroups, but not at all in the glucose-supplemented subgroup. This 20% increase in triglyceride production in the fructose-supplemented subgroup was accompanied by a six times greater (120%) increase in triglyceride concentration. This suggested that dietary fructose not only increased triglyceride production, but also impaired triglyceride removal. Exogenously induced hyperinsulinemia further increased triglyceride production in those rats receiving dietary fructose, either as the monosaccharide or as sucrose, but not in those receiving only glucose. Thus, in the presence of fructose, but not glucose, insulin stimulates triglyceride production. As exogenous insulin returned the triglyceride concentrations to normal in the fructose-supplemented rats, it also appeared to overcome any fructose-associated impairment of triglyceride removal.[Emphasis added.] While fructose is clearly the culprit in triglyceride levels, glucose is not so harmless as the above study might indicate. Perlmutter claims that glucose is very damaging to the brain, and there is research to support a correlation, although not yet a causative relationship:

Our results indicate that even in the absence of manifest type 2 diabetes mellitus or impaired glucose tolerance, chronically higher blood glucose levels exert a negative influence on cognition, possibly mediated by structural changes in learning-relevant brain areas. Therefore, stratgies aimed at lowering glucose levels even in the normal range may beneficially influence cognition in the older population, a hypothesis to be examined in future interventional trials.So it appears that Perlmutter is not so far off after all. He is a little too absolute given the current evidence, but it's not likely that the millions of Americans who read his book are actually going to stop eating wheat and other grain products - Americans are simply not that concerned with the long-term consequences of immediate whims and desires.

Here is a longer talk by Perlmutter being interviewed for Underground Wellness:

Here are time notes:

5:06 -- The impact Dr. Perlmutter had on Dr. Oz.

9:10 -- Why you shouldn't let the government tell you what to eat.

14:42 -- LDL vs oxidized LDL -- know the difference!

17:10 -- 4 vital functions that require cholesterol in the brain.

20:20 -- Why cholesterol should be your BFF, not your worst enemy.

23:43 -- Is whole-grain wheat bread more toxic than a Snickers bar?

29:07 -- Your brain on gluten.

32:20 -- Heard of leaky gut? There's even leaky brain.

34:15 -- Do your kids a favor -- put them on a gluten-free diet.

36:15 -- Dr. Perlmutter's opinion on quinoa.

38:40 -- The antioxidant hoax. And why Sean was right about Protandim.

40:52 -- 5 foods that prevent oxidative stress.

42:00 -- Caller Q: Can gluten-free products still affect the brain?

44:26 -- Caller Q: Is brain fog the result of a gluten sensitivity?

46:47 -- Caller Q: How effective is liposomal glutathione?

49:10 -- Caller Q: If you're on a gluten-free diet, do you only eat protein and vegetables?

51:06 -- Caller Q: Are there other harmful elements in grains beyond gluten?

55:45 -- Caller Q: Is there a difference between the diet Dr. Perlmutter recommends and the paleo diet?

57:30 -- Caller Q: What is Dr. Perlmutter's opinion on the supplement KetoForce?

1:01:24 -- Caller Q: Can you fully recover from damage caused by gluten?

1:03:10 -- Why MS is a gut-related disease

1:09:41 -- Suffering from blood sugar issues? Here's a marker you should test for.

1:15:35 -- How to lower triglycerides.

1:16:33 -- Report your gluten-free success stories to Dr. Perlmutter!

1:17:56 -- The Grain Brain breakdown.