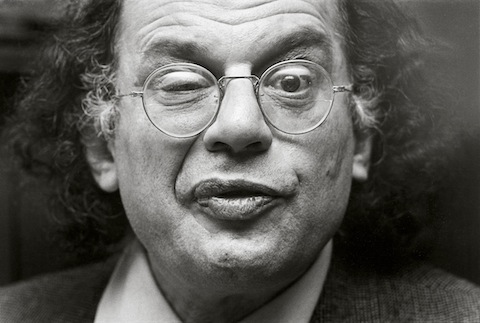

Matt Taibbi is formerly a staff writer for Rolling Stone (he now works with Glenn Greenwald) and has authored several books, including The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap (2014), Griftopia: A Story of Bankers, Politicians, and the Most Audacious Power Grab in American History (2011), The Great Derangement: A Terrifying True Story of War, Politics, and Religion (2009), and Smells Like Dead Elephants: Dispatches from a Rotting Empire (2007), among others.

Because I like you, I am also including a more recent interview with Taibbi from Mother Jones, where Clara Jeffrey (the interviewer in the video below) is the Co-Editor. [Actually, this is just the transcript from the interview in the video, for those who would rather read than listen.]

Matt Taibbi: A Scathing Portrait of American Injustice

4.10.2014 | The Commonwealth Club

Matt Taibbi is perhaps best known for memorably christening Goldman Sachs "a great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity." He has written extensively urging us to think critically about the key institutions and events that shape our country's collective brain. From Griftopia's intense debunking of vested interests and "vampire squid" investment banks to The Great Derangement's thorough examination of the post-9/11 era, Taibbi writes with passion and urgency. In his new book, The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, he continues to passionately decry systemic corruption. This time, however, he turns his focus to examining what he calls "the divide" - the line where troubling trends of mass incarceration and mass inequality meet. He examines the side-by-side existence of criminalized poverty and what he calls the unpunished crimes of the rich. Join us for a challenging, important exchange of ideas.

Speaker Bios

Clara Jeffery is co-editor of Mother Jones, where, together with Monika Bauerlein, she has spearheaded an era of editorial growth and innovation, marked by the addition of now 13-person Washington bureau, an overhaul of the organization's digital strategy and a corresponding 15-fold growth in traffic, and the winning of two National Magazine Awards for general excellence. When Jeffery and Bauerlein received a PEN award for editing in 2012, the judges noted: “With its sharp, compelling blend of investigative long-form journalism, eye-catching infographics and unapologetically confident voice, Mother Jones under Jeffery and Bauerlein has been transformed from what was a respected—if under-the-radar—indie publication to an internationally recognized, powerhouse general-interest periodical influencing everything from the gun-control debate to presidential campaigns. In addition to their success on the print side, Jeffery and Bauerlein’s relentless attention to detail, boundless curiosity and embrace of complex subjects are also reflected on the magazine’s increasingly influential website, whose writers and reporters often put more well-known and deep-pocketed news divisions to shame. Before joining the staff of Mother Jones, Jeffery was a senior editor of Harper's magazine. Fourteen pieces that she personally edited have been finalists for National Magazine Awards, in the categories of essay, profile, reporting, public interest, feature, and fiction. Works she edited have also been selected to appear in various editions of Best American Essays, Best American Travel Writing, Best American Sports Writing, and Best American Science Writing. Clara cut her journalistic teeth at Washington City Paper, where she wrote and edited political, investigative, and narrative features, and was a columnist. Jeffery is a graduate of Carleton College and Northwestern's Medill School of Journalism. She resides in the Mission District of San Francisco with her partner Chris Baum and their son, Milo. Their burrito joint of choice is El Metate.

Matthew C. "Matt" Taibbi is an American author and journalist reporting on politics, media, finance, and sports for Rolling Stone and Men's Journal, often in a polemical style. He has also edited and written for The eXile, the New York Press, and The Beast.

* * * * *

The Man Behind the Vampire Squid: An Interview with Matt Taibbi

A discussion about the financial crisis, unequal treatment under the law—and his choice of metaphors.

—By Clara Jeffery | Sun May 4, 2014

Matt Taibbi speaks to a crowd at an Occupy Wall Street event in February, 2012. John Minchillo/AP

Matt Taibbi has an unmistakable voice in American journalism—assured, addictive, and usually pissed off. After launching his career working for expat papers in Moscow, Taibbi returned to America and trained his sights on politicians and the political process—rich turf for a writer with a knack for spotting and skewering absurdity. After the financial crisis hit in late 2007, Taibbi pivoted to covering the banking sector, penning articles that resonated with the Occupy Wall Street set. (He's the man who memorably labeled Goldman Sachs a "great vampire squid wrapped around the face of humanity, relentlessly jamming its blood funnel into anything that smells like money.") Following years at Rolling Stone, Taibbi recently announced he would join First Look, Pierre Omidyar's news organization, where he will head up a yet-unnamed magazine on financial and political affairs.

I recently interviewed Taibbi about his new book, The Divide: American Injustice in the Age of the Wealth Gap, at InForum, a speaking series hosted by San Francisco's Commonwealth Club. The conversation will be broadcast by 230 public radio stations across the country.

Mother Jones: Matt, you start The Divide by unearthing the story of the Holder Memo, which is pretty obscure. Tell us what it is and how it played a part in the financial crisis.

Matt Taibbi: The Holder Memo goes back to the late nineties when Eric Holder—who was then just an official in the Bill Clinton Justice Department—wrote a memo which has come to be known as the Holder Memo, which was originally thought of as a sort of get tough on crime document. The memo basically provided federal prosecutors with guidelines they could use to go after white-collar offenders. Most people at the time paid attention to the tough aspects of this memo. Among other things, it allowed prosecutors to say to corporate offenders, "we will only give you credit for cooperation if you do things like waive privilege," which was a powerful tool that prosecutors had never had before. So for years, this was thought of as an anti-business document. But at the bottom of the Holder Memo there was this little addendum. It outlined something called the Collateral Consequences Policy, and all Collateral Consequences said was, if you were a prosecutor and you were going after a big, systemically important company that maybe employs a lot of people, and you, the prosecutor, are concerned that there may be innocent victims if you proceed with a criminal case against this company, for instance shareholders or executives who had no role in the wrongdoing, than you may seek alternative remedies apart from criminal prosecutions: fines, deferred prosecution agreements, non-prosecution agreements—all of which is really saying you don't have to prosecute when you have a big company that's done something wrong.

This is a completely sensible policy. It makes a lot of sense. It makes a lot of sense now. The problem is, that when Holder returned to office as attorney general, he came back to a world that was populated by this new kind of corporate offender, the too-big-to-fail bank, which was basically, exactly the kind of company that Collateral Consequences could have been created for. And a lot of these companies have done a lot of very shady things, but Collateral Consequences provided the government with a way to proceed in a way that didn't involve criminal prosecution. It sort of gave the government an excuse to not go forward. Furthermore, even though the intent of this doctrine was to prevent prosecutions against companies, they've begun to conflate it to not proceed against individuals at the companies as well, which I don't think was the original intent the memo, but that seems to have been its legacy now, because we've seen a series of settlements where they haven't proceeded against either the companies or individuals at the companies.

MJ: So do you think the Holder Memo is a symbol of that mentality, or is it an actual factor in the decision to fine and delay prosecutions?

MT: I think it's a combination of both, actually. The existence of the Holder memo—first of all, it was gathering dust for years. After Bill Clinton left office, people forgot about that memo for a long time, until there was an event, it was the collapse of Arthur Andersen. Everyone remembers, of course, this Big Six accounting firm that played a role in the Enron scandal. They were accused of shredding two tons of documents. The government proceeded with a single felony count against the company, the company went under, 27,000 jobs were lost, and politicians everywhere freaked out. And basically there was a general consensus within the law enforcement community that we will never again proceed against a company in this fashion if we can avoid it. That was really when Collateral Consequences was dusted off and reborn; Arthur Andersen was really just a precursor to the decisions we made with regard to the companies implicated in the Great Recession that had done, I would argue, far worse more systemic thing than Arthur Andersen had.

MJ: There's an argument to be made that there have been some massive fines, some gi-normous fines, and trials can be lengthy and super expensive, so what is the argument against just going the fine route?

MT: This is a super important question, because in a vacuum, a lot of this approach of very high fines, coupled with deferred prosecution agreements where they may impose certain conditions on the company—in a vacuum, that may make a lot of sense. It may seem like the best possible solution. The state doesn't have to waste five, six, seven years trying to prosecute a company, you don't have to beat back thousands of motions, and you don't have to worry about perhaps losing a case where you have to expend enormous resources in the first place, so it does make a kind of sense. But the problem is, it falls apart when you think of who doesn't have the option to just buy their way out of jail. And this gets to the whole reason why I wrote this book.

And here I should make a confession: when I decided to write this book, this was right around the time of the Occupy protests, and ironically the financial crisis had sort of been a boon to my career. Before 2008, I was sort of a typical political humorist. I sort of made fun of politicians for a living. That was really all I did, and I had this existential crisis about whether or not that work was valuable at all, and then I got assigned to cover the financial crisis and the causes of it, and I started doing these stories, and I discovered this whole, complicated world of things I never knew about and I had to study. I was doing these pieces basically translating these very complicated and elaborate scams and trying to help broad audiences understand what had happened in 2008, and I thought this was a really worthwhile endeavor, but it was really just an intellectual exercise. I got a charge out of the challenge of deciphering these things and translating it for audiences.

When I'd finished this book, Griftopia, which had done fairly well, so I was getting offers to write another book. And I was trying to think of what I would write about next, and it occurred to me that I should write about the fact that nobody really was going to jail, and somewhat cynically I thought, "This is going to be easy. Morally, this is totally indefensible and all I have to do is tell a few stories about people who had done terrible things and gotten away with it, and boy, will that make people angry, and it'll sell a lot of books, and that'll be easy." And then I started to do my due diligence, I decided to look into who does go to jail in America and why, and I started to become overwhelmed by all these horrible, horrible stories about injustices that were being done to ordinary people who didn't have money. One of the first days I went out, I heard about a thirteen-year-old, mentally disabled, African American boy in Brooklyn who'd been picked up by a couple of cops, and they'd thrown him in the back of a squad car and told him that he couldn't go home that day 'til he helped them find an illegal gun. And so he ended up telling them there was a gun at his grandmother's house, and they descended upon that kid's grandmother's house, they hauled in the grandmother, they hauled in the kid, the hauled in the kid's brother—it's terrible.

I heard story after story. A woman gets arrested, an undocumented immigrant in Los Angeles who gets arrested for driving without a license, and she's sentenced to 170 hours of community service and a $1,700 fine, and she has to take her kids to the community service every night. She's crying herself to sleep every night.

I was overwhelmed, emotionally overwhelmed by all these stories of people who were doing time, who were thrown in jail for varying degrees of absurdity, and it struck me that there was no way to talk about whether or not this Collateral Consequences policy is justified until you actually look in the mirror and ask yourself: Do you really know who's going to jail in this country, and why people going to jail in this country? I was living my life happily not knowing that all these people were being arrested, but it's morally indefensible when somebody can pay a fine and get out of a billion-dollar theft while other people are doing two or three years in jail for reaching into a cash register in a liquor store. That's a very long-winded answer, but the whole point is, you have to look at the two things side-by-side in order to evaluate the policy, and that's what they don't do. When officials defend these policies, they deny the connection that there's any connection between the two problems.

MJ: Backing up for a second to the different ways that, say, bankers were treated and homeowners were treated. Can you talk a little about moral hazard?

MT: Everybody's heard this term "moral hazard," right? This is the idea that, after the financial crisis in 2008, we had all these people who were headed into foreclosure. I think at one point it was four million people who were either in foreclosure or headed for foreclosure, and the argument emanating from Wall Street during this time was that to provide assistance to these people in the form of any kind of a bailout would encourage irresponsibility, because these people had taken on more debt than they could handle, and that was their fault, and they should take responsibility for their actions, and it would just be encouraging more bad behavior if we provided any more assistance to those people. And in some cases, the people who were making that argument were exactly the same people who were taking gigantic bailouts from the United States government. The example I like to cite is Charlie Munger from Berkshire Hathaway who very famously said that people in foreclosure should suck it in and cope. Meanwhile, his company was a major investor in Wells Fargo which was a recipient of TARP money, and he didn't seem to complain too much about getting TARP money, he didn't think that was a moral hazard. But he did think it was a moral hazard for people who were in foreclosure.

What's so funny about this is if you talk to people on Wall Street, they just don't see the hypocrisy of that. It's just a very strange thing.

MJ: Who surprises you most who's not, if not in actually jail, at least came close to being prosecuted. Is there a specific example that you think, "wow, I can't believe these people haven't at least gone to trial?"

MT: Let's talk about Countrywide, for instance. Of course there was a case, there was an SEC case involving Angelo Mozilo, the creator of Countrywide. Countrywide nearly blew up the entire world. The innovation of this company was basically that they were going to give a loan to anything with a pulse. This was part-and-parcel of the whole scam that undermined the entire subprime mortgage crisis. It was a very crude fraud scam, actually. It was just dressed up in a lot of camouflage and jargon. Basically, banks lent billions of dollars to companies like Countrywide who in turn went out to poor and middle class neighborhoods, gave loans out to everyone they could find. I talked to one former mortgage broker who worked for a company like Countrywide who used to go to 7-Elevens at night and hang around the beer cooler, and that's how he found clients to give mortgages to.

Anyway, they would go out and they would create these giant masses of loans. It didn't matter whether they had enough income to pay, it didn't matter whether they were citizens, whether they had identification, whether they were real people at all—whatever. They created the loans, they sold them back to the banks, the banks pooled the loans, they chopped them up into securities, and then they more or less instantly turned around and sold these securities to institutional investors like pension funds, foreign hedge funds, foreign trade unions. In other words, it was this giant scam. You had people who thought they were buying triple-A-rated real estate here in the United States. In fact, they were buying the home loans of extremely risky home buyers here in the US, and Countrywide was at the center of this whole thing. I talked to a whistle-blower at Countrywide who was hired to be part of their quality control team, of all things, and he tells a story of pulling into a parking lot to meet with Angelo Mozilo and his lieutenants, and there's a fancy car in the parking lot that has a personalized license plate that says "FUND EM". And when he asked about it, they were basically like, "Yeah, we give mortgages to everybody who asks."

Their irresponsibility nearly blew up the entire financial system, and Angelo Mozilo made about half-a-billion dollars working at Countrywide, and he was fined by the SEC something on the order of $49 million, most of which was covered by an insurance policy by Bank of America which had by then acquired Countrywide. So he ended up paying, out of his pocket, only about a million, two million dollars. And he walked away with something like $400 million that he got to keep, and he's not doing any time. To me, that's an example of the kind of person—patient zero of the financial crisis. And not only does he not do time, he gets to keep all his money.

MJ: Are there any reforms that have come about that you feel optimistic about?]

MT: I do, I feel there is some momentum, especially in the Senate, for breaking up too big to fail banks. It's an idea that was brought up first during the Dodd-Frank hearings. You might remember the Brown-Kaufman amendment. The idea was basically, if a bank physically exceeded certain parameters, they had to break up into smaller pieces because otherwise they posed a hazard in the sense that if they got in trouble again, we would have to a) bail them out and b) there was the problem that they were unprosecutable, because once they were as big as they are now, Collateral Consequences comes into play: "We can't move against a company like a Chase or a Wells Fargo or a Goldman Sachs or a Morgan Stanley because they've just become too big and too unmanageable."

Brown-Kaufman was routed during the Dodd-Frank negotiations. It was something on the order of 60-something to 30-something, but there's been movement on both sides of the aisle. And people like Sherrod Brown have succeeded in convincing, slowly but surely, Republicans and Democrats, that this too big to fail problem is just untenable.

And also, there's been a lot of support from the heads of the local federal reserve banks, who've also been saying this problem has to change, and this is creating a terrible moral hazard. I do think, while it's probably going to take another disaster, but after that disaster happens, we'll probably end up breaking up some of those companies, and I think that'll be important.

MJ: So bankers, clearly, can't go to jail. Who does, and why, when crime is down, is the prison population five times what it was twenty years ago?

MT: I've asked that question of so many people, and the answer I kept getting was, it's a statistical mystery. Nobody really knows why crime started to go down in the early '90s in the United States, but it has. Violent crime has plunged something on the order of 44 percent since 1990, and it's across the board, it's in all regions of the United States—cities, rural areas, it doesn't matter. Crime is just down. [Editor: Read Kevin Drum on the connection to lead exposure here.]

Some people ascribe it to the aggressive policing strategies like broken windows, the whole idea that we're not going to turn an eye to something like fare jumping or jay walking, and we're going to pick up everybody who does every little thing, and that's been a cornerstone of policing in New York City, where I live. Last year, New York City issued 600,000 summonses for things like riding the wrong way down a sidewalk on a bicycle—that was 20,000 summonses. There were 80,000 for open container violations, 50,000 for marijuana, which is actually, technically decriminalized in New York since 1977, but they use a trick to arrest people for that one. As long as you keep your marijuana in your pocket in New York, they're not supposed to be able to arrest you. But stop and frisk, and, basically, other forms of policing, have allowed cops to profile people and ask them to empty their pockets, and then as soon as they empty their pockets and take the weed out of their pocket, then it's open, and it's in public view, and then that's a crime. So you have someone who is obeying the law and being lawful, and fifty-thousand times last year, they took those people and they turned them into people who had to answer marijuana summonses and go to court for that.

I don't personally believe that's the reason why crime is going down, but I do think that's a big reason why the prison population is going up.

MJ: So what does sending people to jail for low-level possession or "jay biking" do?

MT: Well, it can have all kinds of consequences, not just for that person, but for that person's family. A great example is one that's in the book that involved a couple guys in Harlem, Michael McMichael and Anthony Odem. They were basically arrested for being black and driving a nice car in Harlem. Actually it was the Bronx. The police told them that the probable cause was that they had smelled the odor of marijuana emanating from their car, even though this was winter and the car windows were rolled up and the police had spotted them from blocks away. They pulled these guys over—and the reason they pull over all these people is they're looking for two things, they're looking for guns or warrants, 'cause that's how cops get promoted, they find guns or they catch fugitives. So they're just rolling the dice, figuring a couple black guys in a nice car, they're going to find one or the other. Well, these guys were innocent, it turned out, but rather than let them go, they cooked up this marijuana possession charge, even though there were no drugs in the car, but they said they smelled the odor. Because of that, because these guys had this ridiculous charge hanging over their heads, one of them, Anthony, who was applying for a job at the MTA to be a subway operator, he lost his chance at that job, 'cause you're not allowed to apply for a job if you have a drug charge hanging over you. A lot of times if you get arrested for a drug charge, your relatives might lose their Section A housing. If you get arrested for welfare fraud, you are forever barred from asking for any more public assistance. Again, we talk about collateral consequences for banks, and what the consequences might be for shareholders, but there's all kinds of consequences for people when someone's arrested, and for some reason, we don't have to consider that, but we do have to consider it for the other kind of offender.

MJ: You and I talked a little in the green room about bail, who gets it and what happens if you don't get it, which has some pretty profound effects on future employment, statistically, and the ability to keep rent and so forth. Can you talk a little about how that industry, and how other industries are sort of picking at the carcass of the criminal justice system?

MT: First of all, there's this amazing trick I learned about that involves bail. It happens in many different states. There's a saying in a lot of different courts, if you go in, you stay in, if you get out, you stay out, which basically means if you make bail, you're probably going to beat the case; if you don't make bail, you're probably going to lose the case. What happens in New York, especially, is that if you're charged with a misdemeanor, for instance, and you don't make bail, they have a speedy trial law in New York, where they're supposed to either drop the case or bring you to trial within ninety days. But there's a trick the state is allowed to use to evade that restriction. What they do is, when you have a court date, the prosecutors will show up in court, and they'll say to the judge—I actually saw this happen—they'll say to the judge, "Your Honor, we're not ready to proceed today, one of our witnesses is missing," or whatever it is. And the judge—of course the calendars in these courts are always horribly over-scheduled and stuffed, and he'll look at his calendar, and he'll say, "Well, the next time we can meet is two-and-a-half months from now, so let's write in a date for then." So everybody goes home, but of course the defendant is miserable because he knows he's not going to have a hearing for at least another two-and-a-half more months. But the very next day, what happens is the prosecutor files what's called a "certificate of readiness," which basically means, "while I wasn't ready ready to proceed yesterday, I am ready to proceed today." And the prosecutor knows they're not going to reschedule the court date for that day, the next available hearing is two-and-a-half months from now, so instead of charging the prosecutor for 65 or 70 days toward that ninety-day restriction, they only charge him for one day, and in this fashion, a person can be sitting, awaiting trial for a misdemeanor, not for ninety days but for a year, two years, even more. And as a result, if you don't make bail, what ends up happening is, the prosecutors come to you and say, "Look, we got you, and we're going to offer you a deal: time served plus tens days. You should either take that or leave it, and nine times out of ten people take it, because the alternative is, you might end up serving three or four or five times as much time waiting for trial as you would if you were sentenced. This is why bail is so critical. And of course bail is a non-factor in white collar crimes: unless you're charged with anything short of multiple homicide, you're going to be able to get out on bail for almost anything. It's just an issue that is not talked about very much.

And of course there's the commercial aspect of it, too, where there are companies that are making enormous sums of money on these people who are stuck in the system and are forced to go to bail bondsmen to get money to get out. And it's not a coincidence—I witnessed this myself many times—lawyers have a term for an amount of money judges will set for bail that is just barely too much for the defendant to afford and just too little for a bail bond company to be interested in giving out. They call it nuisance bail, and it's this little sweet spot that the defendants can't afford to pay. Over and over again you'll see somebody who really only has $300 in assets, yet a $400 bail, and that's how people end up in jail. Then through all these other tricks, they end up pleading to these cases.

MJ: We have a piece on commercial bail industry in our upcoming issue, it was actually founded here in San Francisco. The nickname of it was the Old Lady of Kearney Street, which is right around the corner, and it was the fountainhead of city corruption, so declared in a Serpico-level bust of the police department back in the 1930s.

MT: Yay San Francisco.

MJ: There has been positive movement on this front, rolling back mandatory minimums, rolling back three strikes in some cases, De Blasio putting the quash on stop and frisk. Conservatives are kind of leading the way on prison sentence reform in some states because it's a fiscal issue, it's just too expensive. They took a look at the numbers and it doesn't make sense. Is this just sort of a collective awakening, has it gotten so big that we can't afford it, literally?

MT: I'm sure the finances played a key role in that whole situation. With three strikes, the morality of it was the key factor, it's just totally indefensible. One of the cases I covered was someone who got sentenced to life for stealing a pair of $2.50 tube socks. That's politically indefensible, no matter what you think about crime.

I do think the progress is maybe overstated a little bit, because even in New York where stop and frisk is allegedly being rolled back a little bit, I talk to people in neighborhoods like Bedford-Stuyvesant, and they say they'll just come up with some other way of stopping people on the street. They'll come up with some other way of emptying pockets. They'll say they saw a bulge in your pocket or that they saw you conducting a transaction with a friend, and who's going to argue with the probable cause listed in a summons? It takes a lot of energy to overturn, even investigate those sorts of cases. I think it's always going to be politically popular to bang on crime committed in inner cities, and as a result of that, we're always going to have high prison populations from those areas, until, I think, there's a larger awakening to the injustices that are being done.

MJ: You're known for your zingers, particularly your vampire squid line about Goldman Sachs. I'm curious as a writer, did you know when you wrote that line, "This is gold, this is gonna be the one!"?

MT: No, not at all. It was really late at night, I stuck it in the bottom of the piece. It was the editors who put it up at the top. You never know what lines are going to stick and which ones aren't.

One of the reasons I had to use a lot of that kind of language is because this subject matter is so dry and so inaccessible to people that you have to use every trick in your literary arsenal to sex it up for people, and one of the things you especially have to try to do is have fun with things like physical descriptions of people, and use fiction writing techniques in order to play up the black hat vs. white hat aspects of things. I've been criticized for that, for over-dramatizing, and in some cases I guess the criticism is justified. But the problem is, the trade off is if you don't do that, then people aren't going to pay attention at all and they won't be interested in that. So there's a fine line you have to walk between how much color you have to use in these stories and how closely you have to stick to just the facts.

MJ: What was the hardest part to slog through in understanding either the fiscal crisis or the criminal justice system? Derivatives?

MT: Oh, yeah. It was all of that stuff. Are you kidding? I remember the first time I started to read about the financial crisis, it was after the first Sarah Palin speech, September 3, 2008. I was at the convention, and I was in the filing room, and after her speech, I was just about to write up her thing and I'm looking at the internet and seeing that the world is ending, basically, and I turned to a reporter next to me and I'm like, "Dude, have you noticed that the economy is melting down? What's a subprime mortgage, did you understand any of this stuff?" And he looked at me and said, "Pshh." That was his whole reaction, like it wasn't even worth looking into.

I was so worried about this because we don't know anything about the economy and it's blowing up before our eyes, but everyone I talked to just spoke in that impenetrable jargon, and it's really, really difficult to get a read on it. I would call up people and say, "tell me something about something." That's how desperate I was, in the beginning. I would randomly call up analysts—cold call them—and say, "Tell me something understandable." And it wasn't until I found a guy who basically made cartoons about Goldman Sachs who sat me down and he walked me through some very basic things about how subprime mortgages worked and how the collateralized debt obligations worked, and once I got the basics of it…but I would say it took me like three months. It's like learning a language. For anybody who's studied a foreign language, there's that moment when you feel like you can actually converse with people, and it takes a while.

MJ: Do you feel like you'll always have that fluency, or do worry that you're getting rusty?

MT: Well, one of the problems is they're constantly coming up with new innovations. If you're not paying attention, god knows what they'll come up with next, and it's very difficult to stay on top of. Recently, there was this whole scandal in the foreign exchange market, so I have to learn all about currencies, which I've never had to do before. A few months ago I had to do a thing on metals prices, so you have to learn about the metals markets, but that's the job. Journalists are basically like professional test crammers. You have to get up to speed on something you know nothing about by Friday morning when you start Thursday night.

MJ: Your pieces seem to be very fueled by rage. Back in the day, maybe fueled by some other stuff as well, but always there's a level of furry there, I think, and I'm wondering how that helps you propel yourself through a piece, and also does it sometimes make you feel like, "wait, I have to feel on my own personal level a sense of hope." What is that thing you're hopeful about?

MT: I think it's important for a journalist to have a sense of outrage about things. In fact, this is one of the things that sort of motivated me in a certain direction with my career. I started off a long, long time ago, I worked for a newspaper in Moscow called the Moscow Times. It was your basic expatriate newspaper. Everybody wrote in AP style, that kind of very careful, third-person prose. And we'd be writing about things that were sort of epic—scandals, like the loans for shares scandal, which was basically a thing where bunch of Boris Yeltsin's buddies privatized the jewels of the Soviet empire for themselves for free, and we would describe these things and we used a sort of unemotional language, and it occurred to me that if you're writing about something that was outrageous, and you don't write with outrage, that's deceptive. You're lying to your readers when you do that. And you have to find a way to summon the appropriate emotional reaction to the material. I think it's something you have to work at. This is why I told that story about why I got assigned to write this book. I was sort of going through the motions at that point before that. It had become a purely intellectual, professional exercise to sort of write about this stuff.

On this project, it wasn't until I heard that story about that kid who got stuck in the squad car all day long, and I thought about that over, and over, and over again. You just have to stay in touch with that anger, and it's important to do that. I think people can be lulled to sleep by a false impression that everything's cool if they don't see a sense of alarm in television and newspaper coverage.

MJ: After you left the Moscow Times you helped found a really subversive publication called eXile which mercilessly attacked Russian officials, among others. What would the Matt Taibbi of then said to the Vladimir Putin of now?

MT: Well, Vladimir Putin was in office during the last couple years when I was at the eXile. We were actually more upset, not with Putin back then, but with the American reporters who were enabling him. This has all been lost in history now, but when Putin came up through the ranks, he was thought of as a friend of the United States. People thought he was going to be a continuation of the Yeltsin presidency. Yeltsin, of course, was basically a patsy for the United States government, and Putin, being his handpicked successor, was thought of—they used terms like "tecnocrat" to describe him. I remember there was a New York Times story that talked about his past as a KGB agent, and they went into this whole thing about how the KGB wasn't that bad of an organization, and that in the Leningrad of the 1970s where Putin grew up it was a cool career choice for a young man of talent and intelligence. And they made all these excuses for this guy who had not only been a KGB agent but who had been basically a bagman for one of the most corrupt mayors in the history of Russia, which is saying a lot. And we were very, very upset about the fact that the American press was all over this person.

But what would I say to him now? Look, he's been horrible, I was personal friends with a couple of journalists who are no longer with us because of Vladimir Putin, journalists like Anna Politkovskaya, there was another one named Yuri Shchekochikhin, who both met with violent ends for writing about the Putin administration. Putin is a difficult character to summarize easily, because in some ways he's a bit of a hero to the ordinary Russian because he represents standing up to the West, he represents keeping Russia's wealth in Russia, which he did achieve on some level. During the Yeltsin years, Russian capital was flying out of the country and ending up in Swiss banks and the Russian people were suffering. So he's a complicated character, but I think he's morphed into a classic Russian strongman, and that type has reappeared over and over again in Russian history, and it's almost never a good thing.

MJ: There was an infamous story in your past of hitting the New York Times' Moscow bureau chief with a pie with some horse semen in it, but you also followed John Kerry around in a gorilla suit in 2004. You've done these very gonzo stunts. What's the occasion that rises to the need to do that?

MT: Back when we were doing the eXile, our entire mission was to be as crazy as possible. There was a guy, once, who walked across the United States backwards. He started, I think, in New York, and made it all the way to California, and that was sort of the concept of the eXile. We were going to do everything that a newspaper did but in reverse. The corrections would refer to something that had never been in the newspaper. Every single thing in the newspaper was a goof on journalism. We were trying as hard as we could to be ridiculous and absurd. We even, once, purely out of spite and indifference to the wishes of our advertisers, we did a whole issue in French. It was bad French, too. We were young kids and just experimenting with what you could do with the medium. You have to be able to sell a story in addition to being good at telling a story, and the ability to be self-promotional and bring salesmanship to a subject, it is important. I don't think it's so necessary to use a gorilla suit any more, but, for instance, the vampire squid thing, that sort of language and creating a persona, and a narrative voice that people can connect with. That's important. That's the difference between a story that people will read and one that people won't read, and you do have to know when to do that, how to get attention when you need to.

MJ: Coming out of our discussion of combining theater and performance and political critique, I'm wondering what is your takeaway of how the Occupy movement dissipated. If you were to go back and assess what happened there, do you have a single takeaway?

MT: First of all, I think Occupy was great. It was unexpected, it was organic, it developed out of thin air. It wasn't the creation of some foundation that decided it was going to force an issue somewhere. People just came out to the streets and they gathered. Originally I was disillusioned that there wasn't a single coherent goal of Occupy, but over time, I thought that became a strength of the movement because people just sort of came out and they were expressing their general dissatisfaction with something. It was important that we all recognized there was something wrong with our society, and I think that was cool.

To me, the failure of Occupy had a lot to do with who was coming out to protest. I remember going to a foreclosure court in Jacksonville, Florida. There was this little room where a judge sat and this attorney who had been hired by the banks to throw people out of their homes would come in first thing in the morning with a gigantic stack of folders. He was like Dagwood with a sandwich, he was just carrying this gigantic stack of folders. And each one of those represented a family who was going to be thrown out of their house that day, and there was such pure rage in that room of people who were losing their houses, and those people weren't the people protesting at Occupy. And I think if you could combine the people who were the real victims of the financial crisis and of the crime and of the misdeeds and the people who came out at Occupy, then I think you'd have something really dangerous. But they never managed, I thought, to reach all those people.