We, as therapists, see the results of intergenerational trauma (also known as transgenerational trauma) in our offices all of the time, especially with incest and/or neglect. The work of the interpersonal neurobiologists demonstrates that many of the cognitive beliefs and affect dysregulation in mental illness result from faulty or absent attachment bonding.

[

Aside: It's interesting to me that the Native American population uses the term "intergenerational trauma" to discuss what has happened to them, but the Jewish community uses the term "transgenerational trauma" to discuss what their people have endured.]

This new work offers insight into the epigenetic aspect of intergenerational traumas, although their bias seems to be toward a purely biological etiology, which is only a partial understanding of the issue. It's still useful information.

Journal Reference:

Gapp K, Jawaid A, Sarkies P, Bohacek J, Pelczar P, Prados J, Farinelli L, Miska E, Mansuy IM. Implication of sperm RNAs in transgenerational inheritance of the effects of early trauma in mice. Nature Neuroscience, April 13, 2014 DOI: 10.1038/nn.3695

April 13, 2014

Source: ETH Zurich

Summary:

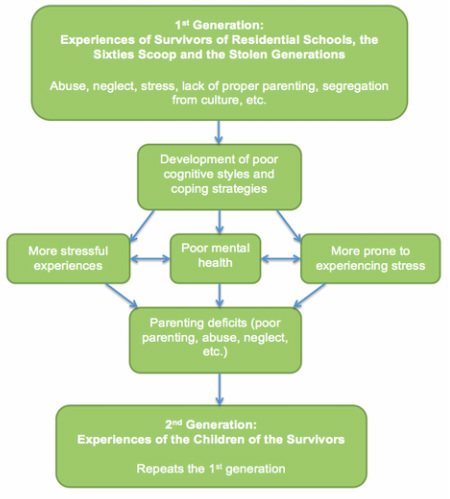

Extreme and traumatic events can change a person -- and often, years later, even affect their children. Researchers have now unmasked a piece in the puzzle of how the inheritance of traumas may be mediated. The phenomenon has long been known in psychology: traumatic experiences can induce behavioural disorders that are passed down from one generation to the next. It is only recently that scientists have begun to understand the physiological processes underlying hereditary trauma

The consequences of traumatic experiences can be passed on from one generation to the next. Credit: Image by Isabelle Mansuy / UZH / Copyright ETH Zurich

Extreme and traumatic events can change a person -- and often, years later, even affect their children. Researchers of the University of Zurich and ETH Zurich have now unmasked a piece in the puzzle of how the inheritance of traumas may be mediated.

The phenomenon has long been known in psychology: traumatic experiences can induce behavioural disorders that are passed down from one generation to the next. It is only recently that scientists have begun to understand the physiological processes underlying hereditary trauma. "There are diseases such as bipolar disorder, that run in families but can't be traced back to a particular gene," explains Isabelle Mansuy, professor at ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich. With her research group at the Brain Research Institute of the University of Zurich, she has been studying the molecular processes involved in non-genetic inheritance of behavioural symptoms induced by traumatic experiences in early life.

Mansuy and her team have succeeded in identifying a key component of these processes: short RNA molecules. These RNAs are synthetized from genetic information (DNA) by enzymes that read specific sections of the DNA (genes) and use them as template to produce corresponding RNAs. Other enzymes then trim these RNAs into mature forms. Cells naturally contain a large number of different short RNA molecules called microRNAs. They have regulatory functions, such as controlling how many copies of a particular protein are made.

Small RNAs with a huge impact

The researchers studied the number and kind of microRNAs expressed by adult mice exposed to traumatic conditions in early life and compared them with non-traumatized mice. They discovered that traumatic stress alters the amount of several microRNAs in the blood, brain and sperm -- while some microRNAs were produced in excess, others were lower than in the corresponding tissues or cells of control animals. These alterations resulted in misregulation of cellular processes normally controlled by these microRNAs.

After traumatic experiences, the mice behaved markedly differently: they partly lost their natural aversion to open spaces and bright light and had depressive-like behaviours. These behavioural symptoms were also transferred to the next generation via sperm, even though the offspring were not exposed to any traumatic stress themselves.

Even passed on to the third generation

The metabolism of the offspring of stressed mice was also impaired: their insulin and blood-sugar levels were lower than in the offspring of non-traumatized parents. "We were able to demonstrate for the first time that traumatic experiences affect metabolism in the long-term and that these changes are hereditary," says Mansuy. The effects on metabolism and behaviour even persisted in the third generation.

"With the imbalance in microRNAs in sperm, we have discovered a key factor through which trauma can be passed on," explains Mansuy. However, certain questions remain open, such as how the dysregulation in short RNAs comes about. "Most likely, it is part of a chain of events that begins with the body producing too much stress hormones."

Importantly, acquired traits other than those induced by trauma could also be inherited through similar mechanisms, the researcher suspects. "The environment leaves traces on the brain, on organs and also on gametes. Through gametes, these traces can be passed to the next generation."

Mansuy and her team are currently studying the role of short RNAs in trauma inheritance in humans. As they were also able to demonstrate the microRNAs imbalance in the blood of traumatized mice and their offspring, the scientists hope that their results may be useful to develop a blood test for diagnostics.

Story Source:

The above story is based on materials provided by ETH Zurich. Note: Materials may be edited for content and length.