This was posted on io9 this morning, and it comes originally from Universe Today. Researchers at the

Large Hadron Collider have discovered a new particle that may be the theoretical tetraquark, and its discovery would mean that of a new form of matter. It also the raises a lot of new possibilities, including the "quark star," for both physics and cosmology."Very simply, the traditional model of a neutron star is that it is made of neutrons. Neutrons consist of three quarks (two down and one up), but it is generally thought that particle interactions within a neutron star are interactions between neutrons. With the existence of tetraquarks, it is possible for neutrons within the core to interact strongly enough to create tetraquarks. This could even lead to the production of pentaquarks and hexaquarks, or even that quarks could interact individually without being bound into color neutral particles. This would produce a hypothetical object known as a quark star."Very cool stuff.

Scientists Detect A Particle That Could Be A New Form Of Matter

Brian Koberlein — Universe Today

Physicists working at the Large Hadron Collider have spotted a long sought-after exotic particle that's the strongest evidence yet for a new form of matter called a tetraquark. Here's what the discovery could mean to astrophysics.

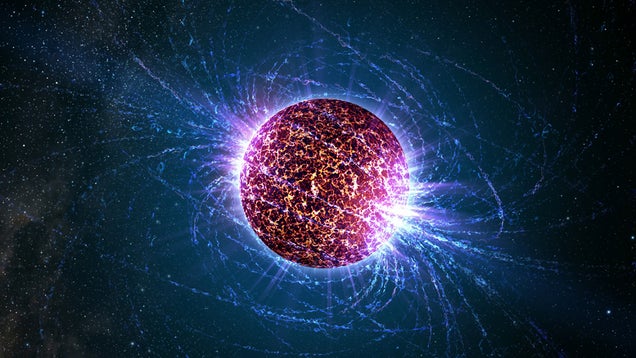

Above: A neutron star. Credit: Casey Reed/Penn State University.

You may have heard that CERN announced the discovery of a strange particle known as Z(4430). A paper summarizing the results has been published on the physics arxiv, which is a repository for preprint (not yet peer reviewed) physics papers.

The new particle is about four times more massive than a proton, has a negative charge, and appears to be a theoretical particle known as a tetraquark. The results are still young, but if this discovery holds up it could have implications for our understanding of neutron stars.

Image: Chandra.

A Horse Of A Different Color

The building blocks of matter are made of leptons (such as the electron and neutrinos) and quarks (which make up protons, neutrons, and other particles). Quarks are very different from other particles in that they have an electric charge that is 1/3 or 2/3 that of the electron and proton. They also possess a different kind of "charge" known as color. Just as electric charges interact through an electromagnetic force, color charges interact through the strong nuclear force. It is the color charge of quarks that works to hold the nuclei of atoms together. Color charge is much more complex than electric charge. With electric charge there is simply positive (+) and its opposite, negative (-). With color, there are three types (red, green, and blue) and their opposites (anti-red, anti-green, and anti-blue).

Because of the way the strong force works, we can never observe a free quark. The strong force requires that quarks always group together to form a particle that is color neutral. For example, a proton consists of three quarks (two up and one down), where each quark is a different color. With visible light, adding red, green and blue light gives you white light, which is colorless. In the same way, combining a red, green and blue quark gives you a particle which is color neutral. This similarity to the color properties of light is why quark charge is named after colors.

The Tetraquark

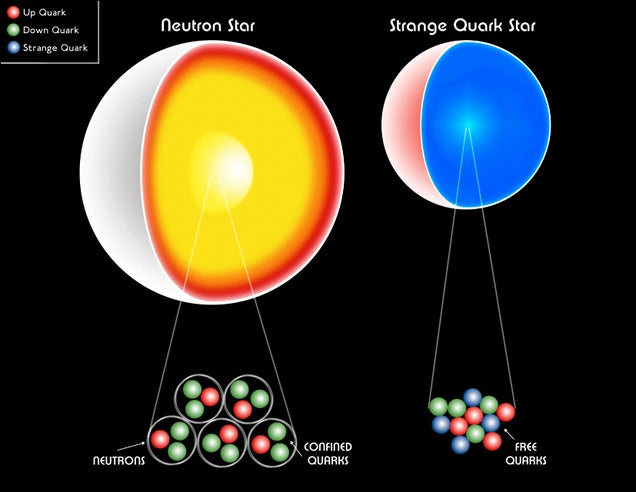

Combining a quark of each color into groups of three is one way to create a color neutral particle, and these are known as baryons. Protons and neutrons are the most common baryons. Another way to combine quarks is to pair a quark of a particular color with a quark of its anti-color. For example, a green quark and an anti-green quark could combine to form a color neutral particle. These two-quark particles are known as mesons, and were first discovered in 1947. For example, the positively charged pion consists of an up quark and an antiparticle down quark.

Under the rules of the strong force, there are other ways quarks could combine to form a neutral particle. One of these, the tetraquark, combines four quarks, where two particles have a particular color and the other two have the corresponding anti-colors. Others, such as the pentaquark (3 colors + a color anti-color pair) and the hexaquark (3 colors + 3 anti-colors) have been proposed. But so far all of these have been hypothetical. While such particles would be color neutral, it is also possible that they aren't stable and would simply decay into baryons and mesons.

The Quark Star

There has been some experimental hints of tetraquarks, but this latest result is the strongest evidence of four quarks forming a color neutral particle. This means that quarks can combine in much more complex ways than we originally expected, and this has implications for the internal structure of neutron stars.

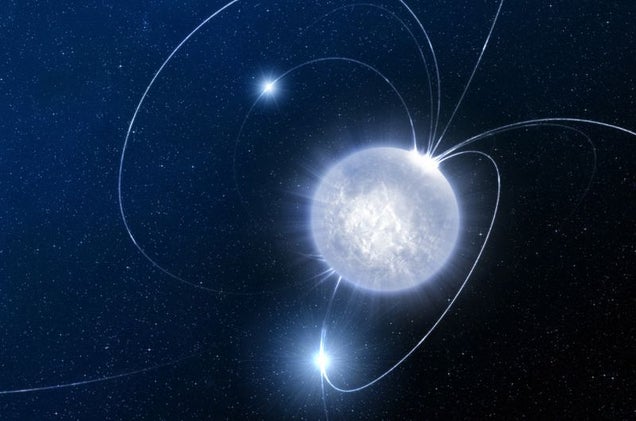

ESO/Luís Calçada.

Very simply, the traditional model of a neutron star is that it is made of neutrons. Neutrons consist of three quarks (two down and one up), but it is generally thought that particle interactions within a neutron star are interactions between neutrons. With the existence of tetraquarks, it is possible for neutrons within the core to interact strongly enough to create tetraquarks. This could even lead to the production of pentaquarks and hexaquarks, or even that quarks could interact individually without being bound into color neutral particles. This would produce a hypothetical object known as a quark star.

This is all hypothetical at this point, but verified evidence of tetraquarks will force astrophysicists to reexamine some the assumptions we have about the interiors of neutron stars.

This article originally appeared at Universe Today.