Rethinking Trauma: The Third Wave of Trauma Treatment

By Ruth Buczynski, PhD

As someone who’s been practicing for a while, I’ve seen our view on the treatment of trauma go through substantial development. Our research, theory and treatments have all advanced considerably in the last 40 years.

And as I reflect upon this, I’m seeing 3 waves in the evolution of our outlook.

Looking back at when I first began to practice (in the late 70’s) our understanding of trauma was really quite limited. Of course we recognized the fight / flight response ever since Hans Selye introduced the notion back in the 50’s.

But our prevailing treatment option was talk therapy.

The thinking at the time was that by getting clients to talk about their traumatic event, we could “get to the bottom of” their issues and help them heal.

We were aware of the body and knew it held some power. But few practitioners used it in treatment (except the relatively few who worked with Bioenergetics, Rolfing, Feldenkrais, Rubenfeld, and to some extent Gestalt therapy).

But we were very limited in our ability to explain how body work, or for that matter, a talking treatment, affected the brain (and we had very little evidence-based research for it either). We just didn’t have much of a roadmap to guide us where we wanted to go.

That was the first wave.

Over time, researchers and clinicians started to recognize the limits of talk therapy. We realized that talking about a traumatic event held certain risks. At times, we inadvertently re-traumatized patients, especially if interventions were introduced too soon, before the patient was ready.

We also saw the memory of trauma as more often held in the right brain, the part that doesn’t really think in words.

So we began to use interventions that weren’t as dependent upon talking, interventions like guided imagery, hypnosis, EMDR, and the various forms of tapping.

And as the science surrounding the brain’s reactions to trauma became more sophisticated, clinicians grew to understand more about what was going on.

We began to realize that not everyone who experiences a traumatic event gets PTSD. In fact, most people who experience a traumatic event don’t get PTSD.

And so researchers started to develop studies to determine who did and who didn’t get PTSD. We looked for what factors might predict greater sensitivity to trauma.

And we modified our thinking to add freeze (later known as feigned death) to the fight/flight reaction.

Just adding that piece clarified our thinking about what triggers PTSD.

It also began to expand our treatment options to include sensory motor approaches.

And we started to see how more vastly intricate and multifaceted multiple trauma was compared to single incident trauma.

But I believe a third wave of trauma research and treatment innovations has just begun to crest.

And it’s only come recently.

In just the past year and a half, pioneers in the field of trauma therapy have once again discovered more effective methods for working with trauma patients.

Because of all the research that’s been done, we are much better able to predict who gets PTSD and who doesn’t. Not only that but we’ve got a good handle on why certain people get PTSD.

And as brain science has revealed how different areas of the brain and nervous system respond to traumatic events, we don’t think so often about whether trauma is stored in the left vs right brain.

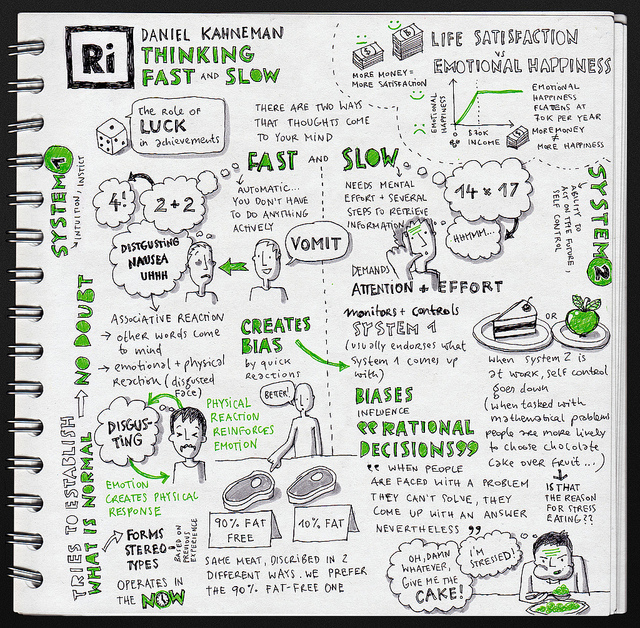

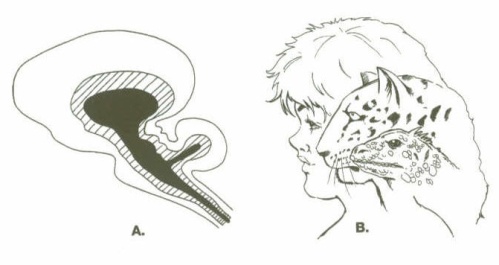

We think in terms of three parts of the brain, the pre-frontal cortex, the limbic brain and the lower, more primitive brain. And we’re much more sophisticated in thinking about which part needs our intervention.

We understand that the lower brain can command the shutdown response, totally bypassing the prefrontal cortex, totally bypassing any sense of “choice” for the patient.

And we see more clearly the part that the vagal system plays in this shutdown response.

We understand more of the role neuroception plays in feeling safe.

Knowing how the body and brain react to trauma opens the door for the third wave.

We are now beginning to use techniques like neurofeedback (based upon but a long way from the biofeedback we used years ago,) limbic system therapy, and other brain and body-oriented approaches that include a polyvagal perspective.

These are techniques I couldn’t have dreamed of when I began clinical practice, and for the most part, they weren’t prevalent five years or even two years ago.

But these are powerful tools that can offer hope to those who have been stuck in cycles of reactivity, shame, and hopelessness.

I’d like to share with you some of the leading edge research and treatment options that this third wave has introduced – for more information, just click here.

And I’d like to hear from you: What changes have you seen in your work with the treatment of trauma? Please leave a comment below.

People turn to grease when they explode, he told us, because their fat cells burst open. He witnessed multiple suicide bombings. Once, he accidentally stepped in an exploded corpse; only the legs were still recognizable as human. Another time, he saw a kitchen full of women sliced to bits. They’d been making couscous when a bomb went off and the windows shattered. He was shot in the back of the head once. He was also injured by an improvised explosive device.

But none of those experiences haunted him quite as much as this one: Several months into his tour, while on a security detail, Eugene killed an innocent man and then watched as the man’s mother discovered the body a short while later.

“Tell us more about that,” van der Kolk said. “What happened?” Eugene’s fragile composure broke at the question. He closed his eyes, covered his face and sobbed.

“The witness can see how distressed you are and how badly you feel,” van der Kolk said. Acknowledging and reflecting the protagonist’s emotions like this — what van der Kolk calls “witnessing” them — is a central part of the exercise, meant to instill a sense of validation and security in the patient.

Eugene had already called on some group members to play certain roles in his story. Kresta, a yoga instructor based in San Francisco, was serving as his “contact person,” a guide who helps the protagonist bear the pain the trauma evokes, usually by sitting nearby and offering a hand to hold or a shoulder to lean on. Dave, a child-abuse survivor and small-business owner in Southern California, was playing Eugene’s “ideal father,” a character whose role is to say all the things that Eugene wished his real father had said but never did. They sat on either side of Eugene, touching his shoulders. Next, van der Kolk asked who should play the man he killed. Eugene picked Sagar, a stand-up comedian and part-time financial consultant from Brooklyn. Finally, van der Kolk asked, Who should play the man’s mother?

Eugene pointed to me. “Can you do it?” he asked.

I swore myself in as the others had, by saying, “I enroll as the mother of the man you killed.” Then I moved my pillow to the center of the room, across from Eugene, next to van der Kolk.

“O.K.,” van der Kolk said. “Tell us more about that day. Tell us what happened.”

Psychomotor therapy is neither widely practiced nor supported by clinical studies. In fact, most licensed psychiatrists probably wouldn’t give it a second glance. It’s hokey-sounding. It was developed by a dancer. But van der Kolk believes strongly that dancers — and musicians and actors — may have something to teach psychiatrists about healing from trauma and that even the hokey-sounding is worthy of our attention. He has spent four decades studying and trying to treat the effects of the worst atrocities we inflict on one another: war, rape, incest, torture and physical and mental abuse. He has written more than 100 peer-reviewed papers on psychological trauma. Trained as a psychiatrist, he treats more than a dozen patients a week in private practice — some have been going to him for many years now — and he oversees a nonprofit clinic in Boston, the Trauma Center, that treats hundreds more. If there’s one thing he’s certain about, it’s that standard treatments are not working. Patients are still suffering, and so are their families. We need to do better.

Van der Kolk takes particular issue with two of the most widely employed techniques in treating trauma: cognitive behavioral therapy and exposure therapy. Exposure therapy involves confronting patients over and over with what most haunts them, until they become desensitized to it. Van der Kolk places the technique “among the worst possible treatments” for trauma. It works less than half the time, he says, and even then does not provide true relief; desensitization is not the same as healing. He holds a similar view of cognitive behavioral therapy, or C.B.T., which seeks to alter behavior through a kind of Socratic dialogue that helps patients recognize the maladaptive connections between their thoughts and their emotions. “Trauma has nothing whatsoever to do with cognition,” he says. “It has to do with your body being reset to interpret the world as a dangerous place.” That reset begins in the deep recesses of the brain with its most primitive structures, regions that, he says, no cognitive therapy can access. “It’s not something you can talk yourself out of.” That view places him on the fringes of the psychiatric mainstream.

It’s not the first time van der Kolk has been there. In the early 1990s, he was a lead defender of repressed-memory therapy, which the Harvard psychologist Richard McNally later called “the worst catastrophe to befall the mental-health field since the lobotomy era.” Van der Kolk served as an expert witness in a string of high-profile sexual-abuse cases that centered on the recovery of repressed memories, testifying that it was possible — common, even — for victims of extreme or repeated sexual trauma to suppress all memory of that trauma and then recall it years later in therapy. He’d seen plenty of such examples in his own patients, he said, and could cite additional cases from the medical literature going back at least 100 years.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, people from all over the country filed scores of legal cases accusing parents, priests and day care workers of horrific sex crimes, which they claimed to have only just remembered with the help of a therapist. For a time, judges and juries were persuaded by the testimony of van der Kolk and others. It made intuitive sense to them that the mind would find a way to shield itself from such deeply traumatic experiences. But as the claims grew more outlandish — alien abductions and secret satanic cults — support for the concept waned. Most research psychologists argued that it was much more likely for so-called repressed memories to have been implanted by suggestive questioning from overzealous doctors and therapists than to have been spontaneously recalled. In time, it became clear that innocent people had been wrongfully persecuted. Families, careers and, in some cases, entire lives were destroyed.

After the dust settled in what was dubbed “the memory wars,” van der Kolk found himself among the casualties. By the end of the decade, his lab at Massachusetts General Hospital was shuttered, and he lost his affiliation with Harvard Medical School. The official reason was a lack of funding, but van der Kolk and his allies believed that the true motives were political.

Van der Kolk folded his clinic into a larger nonprofit organization. He began soliciting philanthropic donations and honed his views on traumatic memory and trauma therapy. He still believed that repressed memories were a common feature of traumatic stress. Traumatic experiences were not being processed into memories, he reasoned, but were somehow getting “stuck in the machine” and then expressed through the body. Many of his colleagues in the psychiatric mainstream spurned these ideas, but he found another, more receptive audience: body-oriented therapists who not only embraced his message but also introduced him to an array of alternative practices. He began using some of those practices with his own patients and then testing them in small-scale studies. Before long, he had built a new network of like-minded researchers, body therapists and loyal friends from his Harvard days.

The group converged around an idea that was powerful in its simplicity. The way to treat psychological trauma was not through the mind but through the body. In so many cases, it was patients’ bodies that had been grossly violated, and it was their bodies that had failed them — legs had not run quickly enough, arms had not pushed powerfully enough, voices had not screamed loudly enough to evade disaster. And it was their bodies that now crumpled under the slightest of stresses — that dove for cover with every car alarm or saw every stranger as an assailant in waiting. How could their minds possibly be healed if they found the bodies that encased those minds so intolerable? “The single most important issue for traumatized people is to find a sense of safety in their own bodies,” van der Kolk says. “Unfortunately, most psychiatrists pay no attention whatsoever to sensate experiences. They simply do not agree that it matters.”

That van der Kolk does think it matters has won him an impressive and diverse fan base. “He’s really a hero,” says Stephen Porges, a professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “He’s been extraordinarily courageous in confronting his own profession and in insisting that we not discount the bodily symptoms of traumatized people as something that’s ‘just in their heads.’"

These days, van der Kolk’s calendar is filled with speaking engagements, from Boston to Amsterdam to Abu Dhabi. This spring, I trailed him down the East Coast and across the country. At each stop, his audience comprised the full spectrum of the therapeutic community: psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, art therapists, yoga therapists, even life coaches. They formed long lines up to the podium to introduce themselves during coffee breaks and hovered around his table at lunchtime, hoping to speak with him. Some pulled out their cellphones and asked to take selfies with him. Most expressed similar sentiments: