But they were kind of stereotyped, in a way, in which they made tools. They didn't make tools with a kind of creativity and the inventiveness that was characteristics of the human beings who came along later.

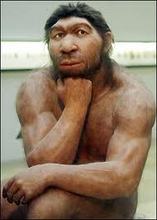

FLATOW: We've heard so many times that, you know, if a Neanderthal were next to you on the subway, you wouldn't know the difference. Is that true, or is that folk - urban folklore?

TATTERSALL: To an extent. I think I would recognize a Neanderthal...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

TATTERSALL: ...if it was next to me in the subway.

FLATOW: And you have every day, on the - right.

TATTERSALL: But, you know, we have considerable experience here in making reconstructions of ancient hominids - reconstructing how they looked in life. And it's very true, that when you sculpt a face onto a skull, you layer on the underlying tissues, the muscles and so forth and then the superficial tissues, and you've got this bold creature with no hair on its head or on its face. The look is very distinctive. It looks very, very different from Homo sapiens. Then when you put the wig on, it's much harder to tell apart.

So that, in fact, we can make this kind of reconstruction and show it in a way in which it stands out from the rest. But if it sat next to you on the subway, you might not have too much of a notion.

FLATOW: I'm Ira Flatow, and this is SCIENCE FRIDAY from NPR. If you'd like to ask a question, you can step up to the microphones we have there. We'd be very happy to talk with Ian Tattersall whose new book is "

Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins." And on the cover, you show three different hands. What are you trying to illustrate with that three different hands?

TATTERSALL: Well, the cover came as a bit of a surprise to me. As a matter of fact...

FLATOW: I hate it when that happens.

TATTERSALL: But...

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

TATTERSALL: But I think it's a very dramatic cover. In fact, what it shows is the hand of, I think, a gibbon or a siamang, and a hand of a chimpanzee, and the hand of a modern human. You can see the hand proportions are very different. And what you have there is two higher primates, two apes with very long, slender hands. So they're very good for grasping branches in the trees. And you'll notice that our own hand is much, much shorter. In fact, it's much broader, The axis of the hand is across, rather than long. And that is what makes it possible for us to manipulate items in the precise way in which we can do and make those stone tools that our predecessors made.

FLATOW: You write that one important factor that is totally unique to hominids and is paradoxical is the possession of complex culture, especially as it's expressed in technology. Can you explain a little bit more about that?

TATTERSALL: Yeah. Obviously, culture is in the strictest sense is not confined to human beings. Chimpanzees, for example, in different parts of Africa pass along, from one generation to another - they pass along particular ways of doing things. But no other creature has a culture of the depth and the richness that human beings have. And human beings have taken culture to a whole new level. And we have come - biologically, we've come a very long way in a very short time.

And I think it's culture that has allowed us to do that because having culture as a buffer against the environment that's allowed different kinds of hominid to spread out over the world and occupy some very marginal environments, which they very often have had to abandoned. There's been this history of fragmenting of the human population which is exactly the circumstances under which you'd expect a lot of evolutionary change to happen.

FLATOW: You also write in your book, that one of the great modifying - or catalysts for change, has been climate change over the years. Can you tell us about that?

TATTERSALL: Yes, indeed. The last several million years have been a time of increasingly unsettled climates. The climate has gotten cold and warm on a larger timescale, as well on smaller timescales too, changing the environment. Any hominid groups staying in the same place would successively encounter lots and lots of different environments and it's ability to accommodate to environmental change which is one of the ingredients for our success in the world. But you have this effect of climate change and fragmentation of populations - human populations couldn't remain in one place forever.

If an ice sheet comes and covers the place where you're living, you're not going to be staying there. You're going to be moving somewhere else more congenial. It's this effect of environmental, climatic and environment change on populations that really has provided the circumstances under which evolutionary innovations could be fixed in populations.

FLATOW: After the break, lots more on human origins with my guest Ian Tattersall, author of the new book "Masters of the Planet." Stay with us.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

FLATOW: I'm Ira Flatow, and this is SCIENCE FRIDAY from NPR.

Welcome back. We're here at the American Museum of Natural History in New York, talking about the new book "

Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins" with my guest Ian Tattersall. He's also curator of the Spitzer Hall of Human Origins here at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Yes, ma'am?

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #1: You have to excuse the simplicity of my question, but it's coming from a sixth-grade student of mine who asked me once: If we evolved from primates, how come there's no evidence of that evolution in primates currently?

TATTERSALL: Well, you know, currently, we're looking at one slice in time. So there's just a sampling of a particular time point.

FLATOW: Can I just interrupt for a second?

TATTERSALL: Yeah.

FLATOW: Point of reference is everybody thinks we came from monkeys.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #1: Right.

FLATOW: Could you clear that up for us? Did we come from monkeys?

TATTERSALL: No. We are not descended from monkeys. But monkeys and we are descended from the same common ancestor.

FLATOW: Thank you. I just want to get that out of the way.

TATTERSALL: Right.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #1: I'll let him know.

TATTERSALL: And the reason why, I think, for example, people say, well, why aren't chimpanzees - if it's such a good idea to get a big brain and to become human-like, why aren't chimpanzees doing the same thing? And I think, quite frankly, that the chimpanzees are already too committed to a particular kind of quadrupedal locomotion on the ground to become upright. Our ancestor was a much more generalized ancestor. It seems that upright walking was the original adaptation of the hominid group - of the general hominid group.

And I suspect that hominids didn't start walking upright on the ground at a time when the forest cover in Africa was shrinking, simply because it was a good idea to do that. I think they've probably - the hominid ancestors probably already moved around in the trees, holding their trunks upright so that when they came down to the ground they would have been most comfortable moving upright. And clearly, that's not true for a chimpanzee today. A chimpanzee, if he wants to move over the ground, effectively, drops to all fours and moves off quadrupedally.

FLATOW: Let's go to a question in the audience. Yes, sir.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: Hi. I was reading an article a while ago that was talking about whether humans will no longer have to evolve because we don't need to adjust to nature anymore because we are adjusting nature ourselves. I was wondering, what's your take on that?

TATTERSALL: Well, I think, first of all, that the human ability to accommodate to the environment culturally meant we could go to many more different areas of the world than we would otherwise have been able to do. And therefore, we're more subject to fragmentation of our population by environmental change. That's one thing. And we evolved in this kind of, sort of, unsettled environmental picture. And human beings for the - or human precursors for the - virtually all of hominid history, have been thinly spread over the landscape.

They have lived in very small densities, in very small groups, moving over large swaths of territory, which again, gives you good circumstances for isolation and evolutionary innovation. Since 10,000 years ago when our species became sedentary, settled down, first started living in villages, then towns and now in urban settings, our population has become huge. Our population is seven billion and increasing, and we're packed, cheek by jowl, over the surface of the Earth.

And these are circumstances in which you could not imagine that significant new genetic innovations could become fixed. Population, the size of ours, is simply - has simply too much genetic inertia to change. So I think as long as demographic circumstances remain the same as they are today, Homo sapiens is going nowhere.

FLATOW: Well, what is the mechanism that's preventing that exactly? You say we're bunched together. There are too many people together. Why is the - why does that stop evolution?

TATTERSALL: It's extremely difficult to get the fixation of any genetic novelty arising in a very, very big population. To get the fixation of genetic novelties which arise spontaneously in populations, you really need to have a small unstable gene pool that can react to this kind of circumstance.

FLATOW: Thank you for that question. Yes, ma'am.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #2: I was wondering if you could talk about how technology is being applied in your field, and maybe how you're using at the museum - to keep things modern, talking about a very old topic.

TATTERSALL: Well, the world is constantly changing, and this is true of paleoanthropology too. The human fossil record is expanding enormously. There are new discoveries that's being announced practically every week. There are new techniques of looking at all data that are becoming available online. So this is a very exciting thing to be involved in, and the problem is more a problem of keeping up with the change rather than thinking of ways to reflect that change.

FLATOW: Mm-hmm. Talking with Ian Tattersall, author of "

Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins." What are some of the big gaps that you think we need to fill in? Or are there gaps in our history that...

TATTERSALL: Well, I think with every new fossil that's found, the probability decreases that anybody will come up with a new fossil, will force everybody to rewrite the textbooks. They used to be obligatory. Every time a new fossil - a human fossil was announced, that the journalist would say, oh, this is going to...

FLATOW: Rewrite the textbooks.

TATTERSALL: ...rewrite the textbooks, yeah. Now, we have a really good human fossil record, and we, I think, are perceiving the general outlines as this sort of very bushy experimental tree. What's really interesting, though, is what we can do with that data we have.

A couple of years ago, I would never have been able to imagine that people would be in a position to reconstitute the diet of the Neanderthals from the little phytoliths, the little grains of mineral material that are gained from plants that are imbedded in the calculus that forms on the Neanderthal teeth. Who would've imagine this? A dentist's nightmare has sort of become a really good source of information about what our relatives did and ate in the past. This kind of thing is happening all the time. And so I'm not seeing huge gaps to be filled, but what I'm saying is a story that is being fleshed out enormously and in ways that are really impossible to anticipate.

FLATOW: Do you think - people always talk about, you know, as we get better technology, maybe we'll be able to reconstruct the DNA of something...

TATTERSALL: Mm-hmm.

FLATOW: ...either, you know, the DNA of a wooly mammoth or maybe the Neanderthal.

TATTERSALL: Mm-hmm.

FLATOW: Do you think that's going to be possible some time?

TATTERSALL: Well, hopefully, it won't be possible in my lifetime. I think it would raise too many ethical questions. Homo sapiens has had a very bad, you know, history in the way in which it has dealt with its close relatives in the fossil and the living records. I mean, Neanderthals are gone now. We're working on the chimpanzees and the orangutans and the gorillas, and after that, that was - it will be the monkeys. I...

FLATOW: You mean losing them all.

TATTERSALL: Losing them. Well...

FLATOW: Losing them, yeah.

TATTERSALL: ...we really are. And my gosh, if we recreated the Neanderthal by some miracle, what would we do with it?

(SOUNDBITE OF LAUGHTER)

TATTERSALL: You know, it would raise some really extraordinary ethical issues that we haven't even began to grapple with.

FLATOW: Yeah. Question in the audience?

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN #3: The word paleo has been a big word on book covers these years, "The Paleo Diets," et cetera, where these folks discussed that the best way for humans to eat is to eat pre-agricultural, in other words no grains, no rice, go back to the meats, go back to the protein and the fruits and the vegetables and the tubers, et cetera. Are you familiar with these books and them discussing how early people ate and how, our digestive system involved and how we should eat? Have you given that any thoughts?

TATTERSALL: Yeah. There's always, you know, there's the Neanderthal diet, "The Caveman Diet," the recommendation that you should eat this and that and the other, but what is quite extraordinary about our hominid family in general is how generalist we are. It's very interesting that there are some chimpanzee groups that live in an environments that are not too different from the kind of environment that our very early bipedal relatives lived in, and they live in a very, very different way. Chimpanzees coming out of the forest into tree-savanna surroundings eat exactly the same things that their relatives in the forest did.

Our precursors coming out of the forest started exploiting a much wider range of foodstuffs from very early on, including, apparently, animal carcasses, at least regionally. And what this tells me is that we are incredibly generalist in terms of what we eat. So I can't imagine what you would describe a natural diet as being.

FLATOW: And in your book you say that tapeworms can actually tell us something about our past diets. How does that work?

TATTERSALL: You know, the tapeworm question is a very interesting one. We - and the idea is that we had to acquire the tapeworm from somewhere, and apparently the tapeworm that infects the human beings is related to a carnivore tapeworm. And probably, the easiest way of transmitting tapeworm cysts or whatever would have been for human beings at a very early stage to be feeding on the same carcasses that had been attacked by carnivores, again pointing towards a propensity for carnivory in early stage.

FLATOW: Do you find yourself still having to defend the idea of human evolution?

TATTERSALL: I think less often than I might fear. We have had very - we've had exhibitions on human evolution looked at by millions of people every year. We have brought original human fossils in to display to the general public to give people an idea of the richness of the record that we're dealing with, and we have run into really rather little objection from the quarter that you're suggesting.

FLATOW: Yeah. Yeah. I'm Ira Flatow, and this is SCIENCE FRIDAY from NPR. Let's go to the, yes, the mic there.

BETH ANN FREED: Hi, Beth Ann Freed(ph). Back to the food, I've heard few things recently about how cooking has affected our evolution and how we - I mean, I work with teeth and I see that our teeth aren't good for much but cooked food. Talking about all of these human ancestral cousins, how many of us had fire? And talking about the generalist nature of diet, which came first, being a generalists or cooking, and how did those come together?

TATTERSALL: You know, that's an excellent question. I think the generalist tendency probably came first because we know our ancestors of three and a half, 4 million years were, presumably now, pursuing a generalist diet. The cooking argument is a very compelling one though, but it's entirely circumstantial. We know that about 2 million years ago, human or hominid brain sizes began to expand. For the first two or 3 million, maybe 4 million years of hominid evolution, brain size relative to body size had flatlined and remained basically in the ape range. And then suddenly, about 2 million years ago, the curve turned sharply upwards, and the human brain sizes, on average, start getting bigger very fast.

Now, there's a penalty to developing a big brain. We may think we have big brains, and so it's got to be a good idea, but, actually, a big brain is a very costly organ to have. Our brains are about 2 percent of our body weight, but they can use up to 25 percent of all the energy...

FLATOW: No kidding.

TATTERSALL: ...that we consume. And so there is a cost to be paid. And there is an argument that you could not have started to increase brain size without increasing the quality of the diet, and the most obvious way to increase the quality of the diet is actually to use cooking to make the nutrients in the diet much more available than they are in the raw state, and this is a very compelling argument. The only problem is that we have no physical evidence...

FLATOW: It's just a theory.

TATTERSALL: ...to support it.

FLATOW: Yeah. It's a theory about how you can get more...

TATTERSALL: Yeah. It's a theory and it's a very beguiling theory, and it could even be true, but we don't have the physical evidence that we would want to substantiate it. In fact, there are people who argue that regular cooking came in quite late. We only begin to find campfires routinely as part of human occupation sites about 400,000 years ago. There is one instance in - from Israel reported of a succession of hearths dating from about 800,000 years ago, but it's an outlier until about 400,000 years ago. So between 2 million years ago when brains started to expand and 400,000 years ago, there's not a lot of really compelling evidence that people were cooking. Inferentially, it's a great story, but we're still looking for the hard evidence.

FLATOW: But in science, a theory is not good enough. You need to have the evidence for it.

TATTERSALL: Well, you know, in science, you know, we make a big thing out of science dealing with testable hypotheses and information, and yet there's a lot that we believe in science that we can't directly test. All we ask is that it be - that what we believe is consistent with what we can't test. And in that perspective, the circumstantial argument for cooking, it still retains a certain amount of attraction.

FLATOW: Yeah. Ian Tattersall, thank you very much for taking time to be with us today.

TATTERSALL: It's been a pleasure.

(SOUNDBITE OF APPLAUSE)

FLATOW: Author of "

Masters of the Planet: The Search for Our Human Origins." You can see the - you can hear the rest of our conversation with Ian Tattersall in our podcast.

Dr Alice Roberts reveals how your body tells the story of human evolution. The way you look, think and behave is a product of a 6 million year struggle for survival.

Dr Alice Roberts reveals how your body tells the story of human evolution. The way you look, think and behave is a product of a 6 million year struggle for survival.