Paul Whiteley, who blogs at Questioning Answers (mostly on autism research), posted this intriguing research summary from Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry on the relationship between the "gut-brain axis" and schizophrenia, which is not a new avenue of research, but is nonetheless still considered a fringe notion in the mainstream schizophrenia research.

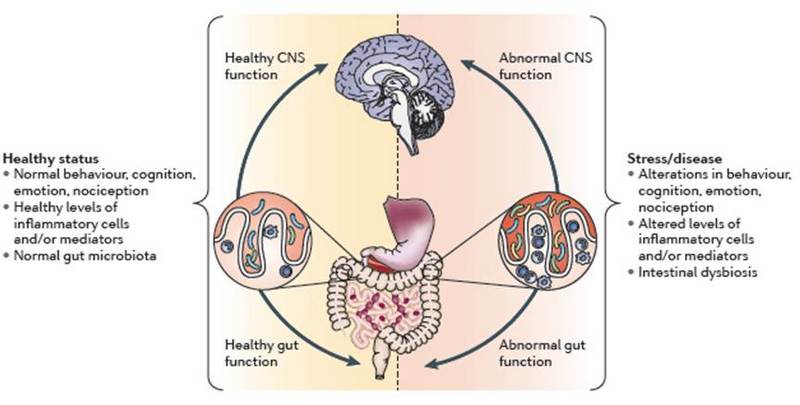

It only makes sense that if we have an unhealthy microbiome (enteric nervous system), which we already know can cause depression, disease, and cognitive issues (a major symptom cluster in schizophrenia is cognitive distortion), then the entire system is at risk.

The full article is, of course, paywalled, but Whiteley offers a good, though too brief for me, summary of the study; and I have included the abstract from the original article.

The gut-brain axis and schizophrenia

Posted by Paul Whiteley

Saturday, 4 October 2014

A micropost to direct your attention to the recent paper by Katlyn Nemani and colleagues [1] titled: 'Schizophrenia and the gut-brain axis'. Mentioning words like that, I couldn't resist offering a little exposure to this review and opinion piece, drawing on what seems to be some renewed research interest in work started by pioneers such as the late Curt Dohan [2].

The usual triad of gastrointestinal (GI) variables - gut barrier, gut bacteria and gut immune function - are mentioned in the article, concluding that: "A significant subgroup of patients may benefit from the initiation of a gluten and casein-free diet" among other things. Not a million miles away from related suggestions when it comes to something like the autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) (see here) bearing in mind the concept of overlapping spectrums (see here) and the [plural] schizophrenias.

I'm also minded to hat-tip another research team including Emily Severance and colleagues who are going great guns when it comes to the whole GI-food link in cases of schizophrenia and beyond (see here for my recent discussion of some of her work). Another of her quite recent papers [3] on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of antibody response to wheat gluten and bovine milk in first-episode schizophrenia represents another master-class of research in this area. Their suggestion of potential evidence for a leaky blood-CSF barrier is something else which might stimulate further research in this area including some mention for the molecular handyperson that is melatonin among other things to "protect against blood-brain barrier and choroid plexus pathologies". Such findings might also be relevant for other CSF issues reported with schizophrenia in mind (see here).

And whilst we're talking all-things biological membrane permeability and schizophrenia, I'll also link to the paper by Julio-Pieper and colleagues [4] (open-access) reviewing some of the evidence on the 'controversial association' between intestinal barrier dysfunction and various conditions (also covering some of the literature with autism in mind too). Mainstream here we come?

----------

[1] Nemani K. et al. Schizophrenia and the gut-brain axis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2014 Sep 17. pii: S0278-5846(14)00168-7

[2] Dohan FC. Cereals and schizophrenia data and hypothesis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1966; 42: 125–152.

[3] Severance EG. et al. IgG dynamics of dietary antigens point to cerebrospinal fluid barrier or flow dysfunction in first-episode schizophrenia. Brain Behav Immun. 2014 Sep 17. pii: S0889-1591(14)00462-0.

[4] Julio-Pieper M. et al. Review article: intestinal barrier dysfunction and central nervous system disorders - a controversial association. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Sep 28.

----------

Nemani, K., Ghomi, R., McCormick, B., & Fan, X. (2014). Schizophrenia and the gut–brain axis. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 56(2): 155–160. DOI: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2014.08.018

* * * * *

Highlights

Abstract

- Several risk factors for the development of schizophrenia can be linked through a common pathway in the intestinal tract

- The microbiota composition may impact the gastrointestinal barrier, immune regulation, and metabolism seen in schizophrenia.

- A significant subgroup of patients may benefit from the initiation of a gluten and casein-free diet

- Antimicrobials and probiotics have therapeutic potential that will be elucidated by further research

Several risk factors for the development of schizophrenia can be linked through a common pathway in the intestinal tract. It is now increasingly recognized that bidirectional communication exists between the brain and the gut that uses neural, hormonal, and immunological routes. An increased incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) barrier dysfunction, food antigen sensitivity, inflammation, and the metabolic syndrome is seen in schizophrenia. These findings may be influenced by the composition of the gut microbiota. A significant subgroup of patients may benefit from the initiation of a gluten and casein-free diet. Antimicrobials and probiotics have therapeutic potential for reducing the metabolic dysfunction and immune dysregulation seen in patients with schizophrenia.