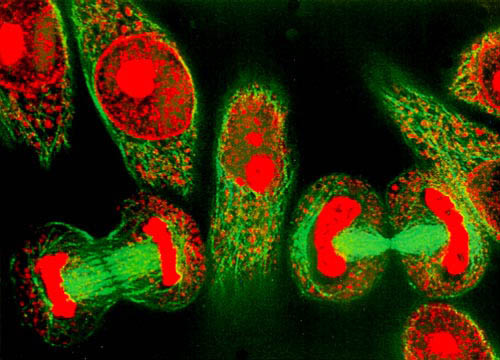

The Secret Micro Universe: The Cell

There is a battle playing out inside your body right now. It started billions of years ago and it is still being fought in every one of us every minute of every day. It is the story of a viral infection – the battle for the cell.

This film reveals the exquisite machinery of the human cell system from within the inner world of the cell itself – from the frenetic membrane surface that acts as a security system for everything passing in and out of the cell, the dynamic highways that transport cargo across the cell and the remarkable turbines that power the whole cellular world to the amazing nucleus housing DNA and the construction of thousands of different proteins all with unique tasks. The virus intends to commandeer this system to one selfish end: to make more viruses. And they will stop at nothing to achieve their goal.

Exploring the very latest ideas about the evolution of life on earth and the bio-chemical processes at the heart of every one of us, and revealing a world smaller than it is possible to comprehend, in a story large enough to fill the biggest imaginations. With contributions from Professor Bonnie L Bassler of Princeton University, Dr Nick Lane and Professor Steve Jones of University College London and Cambridge University’s Susanna Bidgood.

Narrated by David Tennant, this is the story of a battle that has been raging for billions of years and is being fought inside every one of us right now. Swept up in a timeless drama – the fight between man and virus – viewers will see an exciting frontier of biology come alive and be introduced to the complex biochemical processes at the heart of all of us.

The programme features contributions from Professor Bonnie L Bassler of Princeton University, Dr Nick Lane and Professor Steve Jones of UCL, and Cambridge University’s Susanna Bidgood. It is the life story of a single epithelial lung cell on the front line of the longest war in history, waged across the most alien universe imaginable: our battle against viral infection.

David McNab, creative director of Wide-Eyed Entertainment Ltd, commented: “This programme would never have been possible without the guidance, enthusiasm and financial support of the Wellcome Trust. It is the kind of cutting-edge, complex science that needs ambitious visuals to make it accessible to a general audience.

“It has been a privilege to bring to life the work of so many brilliant and dedicated scientists and to reveal a scientific frontier that is both important and genuinely awe-inspiring. I sincerely hope it becomes an inspiration to a new generation of scientists and film-makers.”

Clare Matterson, director of Medical Humanities and Engagement at the Wellcome Trust, says: “‘Secret Universe’ will reveal a world that few people will have seen before, presenting scientifically accurate molecular biology in a gripping visual manner – perfect Sunday night viewing. It is a wonderful example of science programming at its best.”

Wellcome Trust broadcast grants offer support for projects and programmes that engage an audience with issues in biomedical science in an innovative, entertaining and accessible way. Previous programmes funded through the scheme include ‘The Great Sperm Race’ and ‘Inside Nature’s Giants’.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Friday, October 26, 2012

Documentary - The Secret Micro Universe: The Cell

Saturday, September 15, 2012

ENCODE - The ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements

In the following article, Nature offered a comprehensive overview of the ENCODE project - following the article, there are three links that look at the results so far and some of what they suggest.

ENCODE: The human encyclopaedia

First they sequenced it. Now they have surveyed its hinterlands. But no one knows how much more information the human genome holds, or when to stop looking for it.

By Brendan Maher

05 September 2012

Ewan Birney would like to create a printout of all the genomic data that he and his collaborators have been collecting for the past five years as part of ENCODE, the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements. Finding a place to put it would be a challenge, however. Even if it contained 1,000 base pairs per square centimetre, the printout would stretch 16 metres high and at least 30 kilometres long.

ENCODE was designed to pick up where the Human Genome Project left off. Although that massive effort revealed the blueprint of human biology, it quickly became clear that the instruction manual for reading the blueprint was sketchy at best. Researchers could identify in its 3 billion letters many of the regions that code for proteins, but those make up little more than 1% of the genome, contained in around 20,000 genes — a few familiar objects in an otherwise stark and unrecognizable landscape. Many biologists suspected that the information responsible for the wondrous complexity of humans lay somewhere in the ‘deserts’ between the genes. ENCODE, which started in 2003, is a massive data-collection effort designed to populate this terrain. The aim is to catalogue the ‘functional’ DNA sequences that lurk there, learn when and in which cells they are active and trace their effects on how the genome is packaged, regulated and read.

After an initial pilot phase, ENCODE scientists started applying their methods to the entire genome in 2007. Now that phase has come to a close, signalled by the publication of 30 papers, in Nature, Genome Research and Genome Biology. The consortium has assigned some sort of function to roughly 80% of the genome, including more than 70,000 ‘promoter’ regions — the sites, just upstream of genes, where proteins bind to control gene expression — and nearly 400,000 ‘enhancer’ regions that regulate expression of distant genes (see page 57)1. But the job is far from done, says Birney, a computational biologist at the European Molecular Biology Laboratory’s European Bioinformatics Institute in Hinxton, UK, who coordinated the data analysis for ENCODE. He says that some of the mapping efforts are about halfway to completion, and that deeper characterization of everything the genome is doing is probably only 10% finished. A third phase, now getting under way, will fill out the human instruction manual and provide much more detail.

Many who have dipped a cup into the vast stream of data are excited by the prospect. ENCODE has already illuminated some of the genome’s dark corners, creating opportunities to understand how genetic variations affect human traits and diseases. Exploring the myriad regulatory elements revealed by the project and comparing their sequences with those from other mammals promises to reshape scientists’ understanding of how humans evolved.Related stories

Yet some researchers wonder at what point enough will be enough. “I don’t see the runaway train stopping soon,” says Chris Ponting, a computational biologist at the University of Oxford, UK. Although Ponting is supportive of the project’s goals, he does question whether some aspects of ENCODE will provide a return on the investment, which is estimated to have exceeded US$185 million. But Job Dekker, an ENCODE group leader at the University of Massachusetts Medical School in Worcester, says that realizing ENCODE’s potential will require some patience. “It sometimes takes you a long time to know how much can you learn from any given data set,” he says.

Even before the human genome sequence was finished2, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), the main US funder of genomic science, was arguing for a systematic approach to identify functional pieces of DNA. In 2003, it invited biologists to propose pilot projects that would accrue such information on just 1% of the genome, and help to determine which experimental techniques were likely to work best on the whole thing.

The pilot projects transformed biologists’ view of the genome. Even though only a small amount of DNA manufactures protein-coding messenger RNA,for example, the researchers found that much of the genome is ‘transcribed’ into non-coding RNA molecules, some of which are now known to be important regulators of gene expression. And although many geneticists had thought that the functional elements would be those that are most conserved across species, they actually found that many important regulatory sequences have evolved rapidly. The consortium published its results3 in 2007, shortly after the NHGRI had issued a second round of requests, this time asking would-be participants to extend their work to the entire genome. This ‘scale-up’ phase started just as next-generation sequencing machines were taking off, making data acquisition much faster and cheaper. “We produced, I think, five times the data we said we were going to produce without any change in cost,” says John Stamatoyannopoulos, an ENCODE group leader at the University of Washington in Seattle.

The 32 groups, including more than 440 scientists, focused on 24 standard types of experiment (see ‘Making a genome manual’). They isolated and sequenced the RNA transcribed from the genome, and identified the DNA binding sites for about 120 transcription factors. They mapped the regions of the genome that were carpeted by methyl chemical groups, which generally indicate areas in which genes are silent. They examined patterns of chemical modifications made to histone proteins, which help to package DNA into chromosomes and can signal regions where gene expression is boosted or suppressed. And even though the genome is the same in most human cells, how it is used is not. So the teams did these experiments on multiple cell types — at least 147 — resulting in the 1,648 experiments that ENCODE reports on this week1, 4–8.

Stamatoyannopoulos and his collaborators4, for example, mapped the regulatory regions in 125 cell types using an enzyme called DNaseI (see page 75). The enzyme has little effect on the DNA that hugs histones, but it chops up DNA that is bound to other regulatory proteins, such as transcription factors. Sequencing the chopped-up DNA suggests where these proteins bind in the different cell types. The team discovered around 2.9 million of these sites altogether. Roughly one-third were found in only one cell type and just 3,700 showed up in all cell types, suggesting major differences in how the genome is regulated from cell to cell.

The real fun starts when the various data sets are layered together. Experiments looking at histone modifications, for example, reveal patterns that correspond with the borders of the DNaseI-sensitive sites. Then researchers can add data showing exactly which transcription factors bind where, and when. The vast desert regions have now been populated with hundreds of thousands of features that contribute to gene regulation. And every cell type uses different combinations and permutations of these features to generate its unique biology. This richness helps to explain how relatively few protein-coding genes can provide the biological complexity necessary to grow and run a human being. ENCODE “is much more than the sum of the parts”, says Manolis Kellis, a computational genomicist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, who led some of the data-analysis efforts.

The data, which have been released throughout the project, are already helping researchers to make sense of disease genetics. Since 2005, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have spat out thousands of points on the genome in which a single-letter difference, or variant, seems to be associated with disease risk. But almost 90% of these variants fall outside protein-coding genes, so researchers have little clue as to how they might cause or influence disease.

The map created by ENCODE reveals that many of the disease-linked regions include enhancers or other functional sequences. And cell type is important. Kellis’s group looked at some of the variants that are strongly associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, a disease in which the immune system attacks the body’s own tissues. The team noticed that the variants identified in GWAS tended to be in regulatory regions of the genome that were active in an immune-cell line, but not necessarily in other types of cell and Kellis’s postdoc Lucas Ward has created a web portal called HaploReg, which allows researchers to screen variants identified in GWAS against ENCODE data in a systematic way. “We are now, thanks to ENCODE, able to attack much more complex diseases,” Kellis says.

Are we there yet?

Researchers could spend years just working with ENCODE’s existing data — but there is still much more to come. On its website, the University of California, Santa Cruz, has a telling visual representation of ENCODE’s progress: a grid showing which of the 24 experiment types have been done and which of the nearly 180 cell types ENCODE has now examined. It is sparsely populated. A handful of cell lines, including the lab workhorses called HeLa and GM12878, are fairly well filled out. Many, however, have seen just one experiment.

Scientists will fill in many of the blanks as part of the third phase, which Birney refers to as the ‘build out’. But they also plan to add more experiments and cell types. One way to do that is to expand the use of a technique known as chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP), which looks for all sequences bound to a specific protein, including transcription factors and modified histones. Through a painstaking process, researchers develop antibodies for these DNA binding proteins one by one, use those antibodies to pull the protein and any attached DNA out of cell extracts, and then sequence that DNA.

But at least that is a bounded problem, says Birney, because there are thought to be only about 2,000 such proteins to explore. (ENCODE has already sampled about one-tenth of these.) More difficult is figuring out how many cell lines to interrogate. Most of the experiments so far have been performed on lines that grow readily in culture but have unnatural properties. The cell line GM12878, for example, was created from blood cells using a virus that drives the cells to reproduce, and histones or other factors may bind abnormally to its amped-up genome. HeLa was established from a cervical-cancer biopsy more than 50 years ago and is riddled with genomic rearrangements. Birney recently quipped at a talk that it qualifies as a new species.

ENCODE researchers now want to look at cells taken directly from a person. But because many of these cells do not divide in culture, experiments have to be performed on only a small amount of DNA, and some tissues, such as those in the brain, are difficult to sample. ENCODE collaborators are also starting to talk about delving deeper into how variation between people affects the activity of regulatory elements in the genome. “At some places there’s going to be some sequence variation that means a transcription factor is not going to bind here the same way it binds over here,” says Mark Gerstein, a computational biologist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, who helped to design the data architecture for ENCODE. Eventually, researchers could end up looking at samples from dozens to hundreds of people.

The range of experiments is expanding, too. One quickly developing area of study involves looking at interactions between parts of the genome in three-dimensional space. If the intervening DNA loops out of the way, enhancer elements can regulate genes hundreds of thousands of base pairs away, so proteins bound to the enhancer can end up interacting with those attached near the gene. Dekker and his collaborators have been developing a technique to map these interactions. First, they use chemicals that fuse DNA-binding proteins together. Then they cut out the intervening loops and sequence the bound DNA, revealing the distant relationships between regulatory elements. They are now scaling up these efforts to explore the interactions across the genome. “This is beyond the simple annotation of the genome. It’s the next phase,” Dekker says.

The question is, where to stop? Kellis says that some experimental approaches could hit saturation points: if the rate of discoveries falls below a certain threshold, the return on each experiment could become too low to pursue. And, says Kellis, scientists could eventually accumulate enough data to predict the function of unexplored sequences. This process, called imputation, has long been a goal for genome annotation. “I think there’s going to be a phase transition where sometimes imputation is going to be more powerful and more accurate than actually doing the experiments,” Kellis says.

Yet with thousands of cell types to test and a growing set of tools with which to test them, the project could unfold endlessly. “We’re far from finished,” says geneticist Rick Myers of the HudsonAlpha Institute for Biotechnology in Huntsville, Alabama. “You might argue that this could go on forever.” And that worries some people. The pilot ENCODE project cost an estimated $55 million; the scale-up was about $130 million; and the NHGRI could award up to $123 million in the next phase.

Some researchers argue that they have yet to see a solid return on that investment. For one thing, it has been difficult to collect detailed information on how the ENCODE data are being used. Mike Pazin, a programme director at the NHGRI, has scoured the literature for papers in which ENCODE data played a significant part. He has counted about 300, 110 of which come from labs without ENCODE funding. The exercise was complicated, however, because the word ‘encode’ shows up in genetics and genomics papers all the time. “Note to self,” says Pazin wryly, “make up a unique project name next time around.”

A few scientists contacted for this story complain that this isn’t much to show from nearly a decade of work, and that the choices of cell lines and transcription factors have been somewhat arbitrary. Some also think that the money eaten up by the project would be better spent on investigator-initiated, hypothesis-driven projects — a complaint that also arose during the Human Genome Project. But unlike the genome project, which had a clear endpoint, critics say that ENCODE could continue to expand and is essentially unfinishable. (None of the scientists would comment on the record, however, for fear that it would affect their funding or that of their postdocs and graduate students.)

Birney sympathizes with the concern that hypothesis-led research needs more funding, but says that “it’s the wrong approach to put these things up as direct competition”. The NHGRI devotes a lot of its research dollars to big, consortium-led projects such as ENCODE, but it gets just 2% of the total US National Institutes of Health budget, leaving plenty for hypothesis-led work. And Birney argues that the project’s systematic approach will pay dividends. “As mundane as these cataloguing efforts are, you’ve got to put all the parts down on the table before putting it together,” he says.

After all, says Gerstein, it took more than half a century to get from the realization that DNA is the hereditary material of life to the sequence of the human genome. “You could almost imagine that the scientific programme for the next century is really understanding that sequence.”

Nature 489, 46–48 (06 September 2012) | doi:10.1038/489046a

References

-

The ENCODE Project Consortium Nature 489, 57–74 (2012).

Show context

-

International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium Nature 431, 931–945 (2004).

Show context

-

The ENCODE Project Consortium Nature 447, 799–816 (2007).

Show context

-

Thurman, R. E. et al. Nature 489, 75–82 (2012).

Show context

-

Neph, S. et al. Nature 489, 83–90 (2012).

Show context

-

Gerstein, M. B. et al. Nature 489, 91–100 (2012).

Show context

-

Djebali, S. et al. Nature 489, 101–108 (2012).

Show context

-

Sanyal, A., Lajoie, B. R., Jain, G. & Dekker, J. Nature 489, 109–113 (2012).

Show context

Related stories and links:

- The truly provocative and disturbing stuff in ENCODE - By Mike White at The Finch & Pea

- This 100,000 word post on the ENCODE media bonanza will cure cancer - By Michael Eisen at It Is Not Junk

- Fighting about ENCODE and junk - By Brendan Maher at Nature News

- Genomics: ENCODE explained by Joseph R. Ecker, Wendy A. Bickmore, Inês Barroso, Jonathan K. Pritchard, Yoav Gilad & Eran Segal at Nature

Wednesday, March 09, 2011

Scripps Research and MIT scientists discover class of potent anti-cancer compounds

Important discovery - each breakthrough gets us closer to a cure or at least a way to slow it down or prevent it in the first place. If you want to know more - in the geeky science sense - check out this article, A Protein Phosphatase Methylesterase (PME-1) Is One of Several Novel Proteins Stably Associating with Two Inactive Mutants of Protein Phosphatase 2A.

Scripps Research and MIT scientists discover class of potent anti-cancer compounds

Posted On: March 7, 2011 - 8:30pmLA JOLLA, CA, AND JUPITER, FL – March 7, 2011 – Embargoed by the journal PNAS until March 7, 2011, 3 PM, Eastern time –Working as part of a public program to screen compounds to find potential medicines and other biologically useful molecules, scientists from The Scripps Research Institute and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have discovered an extremely potent class of potential anti-cancer and anti-neurodegenerative disorder compounds. The scientists hope their findings will one day lead to new therapies for cancer and Alzheimer's disease patients.

The research—scheduled for publication in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) the week of March 7, 2011—was led by Benjamin F. Cravatt III, professor and chair of the Department of Chemical Physiology at Scripps Research and a member of its Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology, and MIT chemistry professor Gregory Fu.

"It was immediately clear that a single class of compounds stood out," said Daniel Bachovchin, a graduate student in the Cravatt lab and the study's first author. "The fact that these compounds work so potently and selectively in cancer cells and mice, right off the screening deck and before we'd done any medicinal chemistry, is very encouraging and also very unusual."

Browsing in the Public Library

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Common Fund Molecular Libraries Program currently funds nine screening and medicinal chemistry-related centers at academic institutions around the United States to enable scientists to find biologically interesting molecules, independently of commercial labs (http://mli.nih.gov/mli/mlpcn/mlpcn-probe-production-centers/). In these centers, academic scientists can test thousands of compounds at once through high-throughput screens against various biological targets to uncover "proof-of-concept" molecules useful in studying human health and in developing new treatments for human diseases.

"Initially the compounds in the NIH Molecular Libraries repository were purchased from commercial sources and augmented through chemical diversity initiatives," explained Ingrid Y. Li, director of the Molecular Libraries Program at the NIH National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). "In recent years we've also encouraged academics to donate structurally unusual compounds, to add novelty to the library." (See http://mli.nih.gov/mli/compound-repository/.)

In 2008, Fu's lab donated a set of molecules known as aza-beta-lactams (ABLs)— molecular cousins of penicillin and other beta-lactam antibiotics. "These were molecules that probably didn't exist in commercial compound libraries, and their bioactivity had been virtually unexplored," said Fu.

Meanwhile, across the country, in the Cravatt lab at Scripps Research campus in La Jolla, California, Bachovchin was developing an unusually fast and flexible test for enzyme activity, using fluorescent molecular probes that bind to an enzyme's active site. Researchers can use such tests to measure whether an enzyme of interest loses its activity in the presence of another chemical compound. Bachovchin, Cravatt, and their colleagues decided to apply the new technique to the NIH compound library, to find an inhibitor for an enzyme known as PME-1 (phosphatase methylesterase 1).

Long seen as a potential high-value drug target, PME-1 chemically modifies a growth-slowing enzyme, known as PP2A, in a way that negates PP2A's ability to serve as a tumor suppressor. Studies have shown that when PME-1 production is reduced in some kinds of brain cancer cells, the tumor-suppressing activity of PP2A increases, and cancerous growth is slowed or stopped. Researchers also have found hints that PME-1 might play a role in promoting Alzheimer's disease, by regulating PP2A's ability to dephosphoryate the Alzheimer's-associated tau protein.

"Despite its importance, no one had been able to develop a PME-1 inhibitor, mainly because standard substrate assays for the enzyme were difficult to adapt for high-throughput screening," said Cravatt. "But we believed that we could use our new 'substrate-free' screening technology for PME-1; and we knew that we needed to try a large, high-throughput screen, because our small-scale efforts to find PME-1 inhibitors had come up empty."

Scripps Research runs an NIH Molecular Libraries Program screening center at its Jupiter, Florida campus. There, the institute's researchers set up an automated version of Bachovchin's new screening technique and used it to search for strong PME-1 inhibitors among the 300,000-plus small-molecule compounds in the NIH library.

Super Potent, Super Selective

Like many molecules, ABLs can exist in two mirror-image versions, known as enantiomers, and they usually are synthesized as an equal mixture of both compounds. But Fu and his group had used new chemistry techniques to produce the ABLs in an "enantiomerically selective" way, in case one enantiomer of a compound had more activity than its mirror-image twin. And, in fact, one of these enantiomeric molecules, ABL127, turned out to fit so precisely into a nook on PME-1 that it completely blocked PME-1 activity in cell cultures and in the brains of mice. Aside from being extremely potent, it also was highly selective for PME-1, so that even at higher doses, it had negligible effects on other enzymes in the PME-1 family, known as serine hydrolases. In mice, ABL127's inhibition of PME-1 activity caused a more than one-third drop in the measured level of demethylated ("inactive") PP2A.

The Cravatt and Fu labs are now working together to synthesize more ABLs and explore their chemistry, looking for the best possible PME-1 inhibitor. The near-term goal is to use ABL127 as a scientific probe to study PME-1 functions in animals. A longer-term goal is to develop ABL127, or related compounds, as potential oncology or Alzheimer's disease drugs.

"Already several labs from both academia and industry have contacted us about collaborating on PME-1 research," said Cravatt. "So our findings here are scientifically interesting, and I think could, one day, be valuable clinically. But it's important to emphasize that we wouldn't have these findings at all, were it not for the NIH Molecular Libraries Program and its compound library. Both on the screening side and the chemistry side, the NIH enabled us academics to bring technologies to the table unlikely to be found in a traditional 'pharma' setting. Our discoveries thus stand as a fine example of the value of public screening for creating novel, in vivo-active pharmacological probes for challenging protein targets."

The paper's other co-authors were Justin T. Mohr and Jacob M. Berlin of the Fu laboratory at MIT; Timothy P. Spicer, Virneliz Fernandez-Vega, Peter Chase, Peter S. Hodder, and Stephan C. Schürer of the Scripps Molecular Screening Center in Jupiter, Florida; and Anna E. Speers, Chu Wang, Daniel K. Nomura and Hugh Rosen of the Scripps Research campus in La Jolla, California.

The activities described in this release are funded through the National Institutes of Health (MH084512, CA132630, and GM57034).

Source: Scripps Research Institute