Yes, compassion is hard-wired and I am glad to see more people talking about it. This comes from Larry Gallagher at Ode Magazine.

The compassion instinct

Research shows that a compassionate attitude towards others improves mental and physical health.

Larry Gallagher | July/August 2011 issue

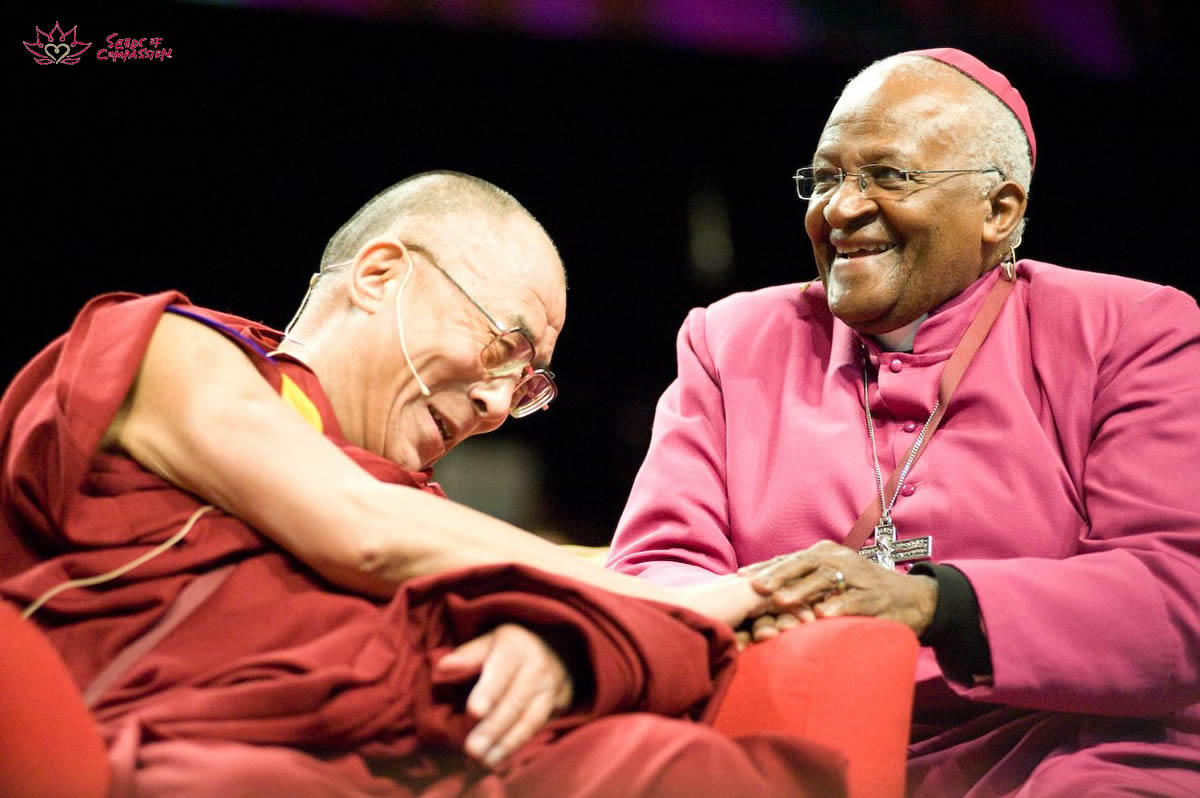

The Dalai Lama has been telling us for years that it would make us happy, but he never said it would make us healthy, too.

“If you want others to be happy,” reads the first part of his famous formula, “practice compassion.” Then comes the second part of the prescription: “If you want to be happy, practice compassion.”

Maybe the Dalai Lama knew all along or maybe he’s just finding out like the rest of us, but science is starting to catch up with a couple millennia of Buddhist thought. In recent years, the investigation of compassion has moved beyond theology and philosophy to embrace a wide range of scientific fields, including neurology, endocrinology and immunology. And while the benefits of being the recipient of compassion are obvious, new research shows that the practice of compassion has beneficial effects not only on mental health but on physical health, too.

Which is good news for everyone on the planet, as you can never have too much compassion. Job layoffs and home foreclosures, the cultural erasure of Tibet and the abscess that is Gaza, the sorrows of disease, natural disasters and death that are always with us: To create a short list makes one guilty of omission. Despite all the progress and advances we have made, there is still plenty about which to feel compassion.

So it can only be good news that in the last decade, the study of compassion and its associated emotions has caught the interest of science, with programs on affective neuroscience, as it is known, blossoming at places like Emory University, Harvard University and University of California, Los Angeles, to name but a few. In 2008, the Dalai Lama donated $150,000 to help kick start the Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education (CCARE) at Stanford University in California. In 2010, he gave a chunk to the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds, an offshoot of the Lab for Affective Neuroscience at the University of Wisconsin.

Here’s even better news: We can train ourselves to be compassionate. In Europe, leading compassion researcher Tania Singer, director of the Department of Social Neuroscience, a wing of the Max Planck Institute in Leipzig, Germany, is exploring the use of brain imaging and biofeedback to teach subjects to activate parts of the brain associated with compassion. “One of our major goals is to see how we can actually train [people in] compassion in Western society,” she says, “not using one-to-one practices from Asia, but to see how we can integrate such training into our very busy and stressful everyday lives.”

Compassion starts with taking time out of our busy and stressful lives to empathize, which is the ability to register and mirror the feelings of our fellow creatures. But compassion takes this empathic response and adds the strong desire to alleviate that suffering.

From a social evolutionary point of view, compassion has long been considered something of an aberration, even a weakness. For Dacher Keltner, director of the Greater Good Science Center at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of Born to Be Good, this is a major oversight. “We missed one of the most central elements in our physical evolution that has implications for gene replication,” says Keltner.

No comments:

Post a Comment