Received an email about this topic from a psychologist friend, Durwin Foster, B.Ed., M.A. (Canadian Certified Counselor; British Columbia Certified Teacher) - I think Developmental Trauma Disorder is a useful diagnostic category worthy of support.

This article is the proposition submitted to the APA's DSM-s committee. See below for how you can help support the research needed to get this into the DSM-5.

Read the whole article.

Bessel A. van der Kolk, MD, Robert S. Pynoos, MD, Dante Cicchetti, PhD, Marylene Cloitre, PhD, Wendy D’Andrea, PhD, Julian D. Ford, PhD, Alicia F. Lieberman, PhD, Frank W. Putnam, MD, Glenn Saxe, MD, Joseph Spinazzola, PhD, Bradley C. Stolbach, PhD, Martin Teicher, MD, PhD

February 2, 2009

Statement of Purpose

The goal of introducing the diagnosis of Developmental Trauma Disorder is to capture the reality of the clinical presentations of children and adolescents exposed to chronic interpersonal trauma and thereby guide clinicians to develop and utilize effective interventions and for researchers to study the neurobiology and transmission of chronic interpersonal violence. Whether or not they exhibit symptoms of PTSD, children who have developed in the context of ongoing danger, maltreatment, and inadequate caregiving systems are ill-served by the current diagnostic system, as it frequently leads to no diagnosis, multiple unrelated diagnoses, an emphasis on behavioral control without recognition of interpersonal trauma and lack of safety in the etiology of symptoms, and a lack of attention to ameliorating the developmental disruptions that underlie the symptoms. What follows are our proposed diagnostic criteria, a brief review of published and unpublished data, rationale and assessment of the reliability and validity data which bear upon this topic, as well as the justification for meeting the criteria for creating a new diagnosis in the DSM V.

Introduction

The introduction of PTSD in the psychiatric classification system in 1980 has led to extensive scientific studies of that diagnosis. However, over the past 25 years there has been a relatively independent and parallel emergence of the field of Developmental Psychopathology (e.g. Maughan & Cicchetti, 2002; Putnam, Trickett, Yehuda, & McFarlane, 1997), which has documented the effects of interpersonal trauma and disruption of caregiving systems on the development of affect regulation, attention, cognition, perception, and interpersonal relationships. A third significant development has been the increasing documentation of the effects of adverse early life experiences on brain development (e.g. De Bellis et al., 2002; Teicher et al., 2003), neuroendocrinology (e.g.Hart, Gunnar, & Cicchetti, 1995; Lipschitz et al., 2003) and immunology (e.g. Putnam et al., 1997; Wilson et al, 1999).

Studies of both child and adult populations over the last 25 years have established that, in a majority of trauma-exposed individuals, traumatic stress in childhood does not occur in isolation, but rather is characterized by co-occurring, often chronic, types of victimization and other adverse experiences (Anda et al., 2006; Dong et al., 2004; Pynoos et al., 2008; Spinazzola et al., 2005; van der Kolk et al, 2005). The impetus for the field trial for Disorders of Extreme Stress (DES) for the DSM IV (Pelcovitz, Kaplan, DeRosa, Mandel, & Salzinger, 2000; Roth, Newman, Pelcovitz, van der Kolk, & Mandel, 1997; van der Kolk, Pelcovitz, Roth, & Mandel, 1996) was to describe the psychopathology of adults who, as children, had been traumatized by interpersonal violence in the context of inadequate caregiving systems. This retrospective study clearly demonstrated the differential impact of interpersonal trauma on adults who as children were exposed to chronic interpersonal trauma, compared to patients who, as mature adults, had been exposed to assaults, disasters or accidents. The DES symptom constellation was ultimately incorporated in the DSM IV as “associated features of PTSD.”

The recognition of the profound difference between adult onset PTSD and the clinical effects of interpersonal violence on children, as well as the need to develop effective treatments for these children, were the principal reasons for the establishment of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network in 2001. Less than eight years later it has become evident that the current diagnostic classification system is inadequate for the tens of thousands of traumatized children receiving psychiatric care for traumarelated difficulties.

PTSD is a frequent consequence of single traumatic events (Green et al., 2000). Research also supports that PTSD, with minor modifications, also is an adequate diagnosis to capture the effects of single incidence trauma in children who live in safe and predictable caregiving systems. Even as many children with complex trauma histories exhibit some symptoms of PTSD (see, e.g., Chicago Child Trauma Center data below), multiple databases (see below) show that the diagnosis of PTSD does not adequately capture the symptoms of children who are victims of interpersonal violence in the context of inadequate caregiving systems. In fact, multiple studies show that the majority meet criteria for multiple other DSM diagnoses. In one study of 364 abused children (Ackerman, Newton, McPherson, Jones, & Dykman, 1998), 58% had the primary diagnosis of separation anxiety/overanxious disorders, 36% phobic disorders, 35% PTSD, 22% attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and 22% oppositional defiant disorder. In a prospective study by Noll, Trickett and Putnam (2003) of a group of sexually abused girls, anxiety, oppositional defiant disorder and phobia were clustered in one group, while depression, suicidality, PTSD, ADHD and conduct disorder represented another cluster.

A survey of 1,699 children receiving trauma-focused treatment across 25 network sites of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (Spinazzola et al, 2005) showed that the vast majority (78%) was exposed to multiple and/or prolonged interpersonal trauma, with a modal 3 trauma exposure types; less than ¼ met diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Fewer than 10% were exposed to serious accidents or medical illness. Most children exhibited posttraumatic sequelae not captured by PTSD: at least 50% had significant disturbances in affect regulation; attention & concentration; negative selfimage; impulse control; aggression & risk taking. These findings are in line with the voluminous epidemiological, biological and psychological research on the impact of childhood interpersonal trauma of the past two decades that has studied its effects on tens of thousands of children. Because no other diagnostic options are currently available, these symptoms currently would need to be relegated to a variety of seemingly unrelated co-morbidities, such as bipolar disorder, ADHD, PTSD, conduct disorder, phobic anxiety, reactive attachment disorder and separation anxiety. Analysis of data from the Chicago Child Trauma Center found that children who experienced ongoing traumatic stress in combination with inadequate caregiving systems were 1.5 times more likely than other trauma-exposed children to meet criteria for non-trauma related diagnoses. Given the data, it is critical to find a way out of this morass of multiple comorbid diagnoses and to identify a new diagnostic category that explains the profusion of symptoms in these children.

The primary reason for introducing the diagnosis of Developmental Trauma Disorder is to capture the reality of the clinical presentations of children and adolescents exposed to chronic interpersonal trauma and thereby to guide clinicians to develop and utilize effective interventions and for researchers to study the neurobiology and transmission of chronic interpersonal violence. Whether or not they exhibit symptoms of PTSD, children who have developed in the context of ongoing danger, maltreatment, and inadequate caregiving systems, are ill-served by the current diagnostic system, as it frequently leads to no diagnosis, multiple unrelated diagnoses, an emphasis on behavioral control without recognition of interpersonal trauma in the etiology of symptoms, and a lack of attention to ameliorating the developmental disruptions underlying symptoms. Three problems with the current diagnostic system have been revealed for maltreated children: no diagnosis, inaccurate diagnosis, and inadequate diagnosis.

Here's how you can help support the research for this diagnosis.

Contribute to the Field Trial for Developmental Trauma Disorder

There currently is an ongoing field trial for the NCTSN proposed Developmental Trauma Disorder for inclusion in the DSM V, in which the University of Connecticut (Dr. Julian Ford), the Trauma Center at JRI (Drs. van der Kolk, Spinazzola and D'Andrea), and LaRabida Hospital in Chicago (Dr. Bradley Stolbach) are the principal sites. Part of this field trial is underwritten by several private foundations, but we are seeking an additional $150,000 to complete this study.

If you would like to make a tax-deductible contribution to help us complete this essential component to having Developmental Trauma Disorder included in the DSM V, please choose one of three following payment methods:

(1) Address a check to DTD Field Trial - Trauma Center at JRI and mail it to:

The Trauma Center at JRI

Attn: Lee Fallontowne, Office Manager

1269 Beacon Street

Brookline, MA 02446

(2) Make a contribution with your credit card via PayPal© by clicking on the button below.

(3) Authorize an automatic payment option with direct withdrawal from your bank account to make recurring payments over time. Please CLICK HERE to view instructions on how to set up this method.

Repeated Trauma in Childhood -

repeated Trouble in Adulthood The name for this group of problems is still not standardised. Psychiatrists, psychotherapists and counsellors are still coming to terms with the profound realisation that continued or regular traumatic experiences during childhood produce a wide range of symptoms in adulthood that may appear to be separate and are often diagnosed as different disorders, but are in fact linked to the same common cause.

Current terms being used include:

Developmental Trauma Disorder

Childhood Developmental Trauma

Complex Childhood Trauma

Repeated Childhood Trauma

Early Relational Trauma

The bottom line for self awareness and self empowerment work and voice dialogue is that so much of what we discover about ourselves and our inner selves and what those selves do, all goes back to the time when we were “copping” with regular or continued traumatic experiences in those early years from age 0 to 10.

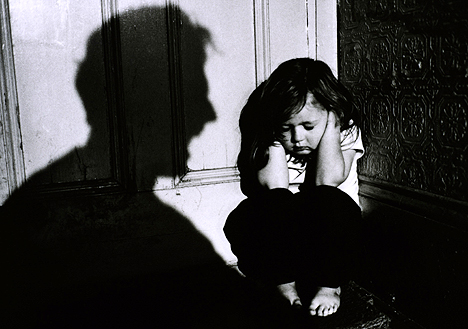

Repeated childhood trauma is a polite term for any form of abuse that a child experiences again and again during the vital life skill developmental stage between age 0 to 10

In non-psychological terms that repeated childhood trauma:

1. Damages or destroys a number of skills we need to operate as a functional adult.

2. Stops us learning other life skills that would help us “master” the kinds of everyday problems that life serves up to us

3. Results in a wide range of behaviour symptoms than may be misdiagnosed as classic psychiatric disorders but are actually more like a “collection of missing life skills”

TYPES OF REGULAR OR REPEATED CHILDHOOD TRAUMA /ABUSE

Physical, Mental, Verbal, Emotional, Spiritual, Sexual, Violence, Shaming, Distorted Reality, Abandonment, Engulfment, Hidden secrets, Excessive control or negativity

FEELINGS CONNECTED WITH REGULAR CHILDHOOD TRAUMA /ABUSE

Lonely, hurt, sad, angry, fear, shame, guilt, worthless, frustration, pain, betrayed, defeated, helpless, hopeless, lost, shut down, devastated, embarrassed, smothered, annoyed, enraged

ADULT BEHAVIOUR RESULTING FROM REGULAR CHILDHOOD TRAUMA /ABUSE

Hyper-arousal – either excessively busy, unable to relax, hyper-vigilant, excessive agitation or irritability, regular states of extreme rage and or aggression.

But what we often see as well is . . .

Hypo- arousal – in which a person disengages and dissociates under stress - In this state the brain’s ‘red phone’ compelling the mind to take action, is dead.

(Dr. Allan Schore, UCLA Psychiatry Department, and Bessel van der Kolk)What can you do about it ? Click here

- Loss of the life skill called “mastery” the feeling of being in charge, calm, and able to engage in focused efforts to accomplish goals.

- Physical pain and body discomfort

- Addictive cycles

- Black and white thinking or flipping between two opposite positions. Either “I love him or I hate him” with nothing in between

Notes from Dr Bessel A van der Kolk ...

Many people who ..... “experience multiple forms of trauma / abuse experience developmental delays across a broad spectrum, including cognitive, language, motor, and socialization skills, they tend to display very complex disturbances, with a variety of different, often fluctuating, presentations.”

“Mastery is most of all a physical experience,” writes Van der Kolk “ the feeling of being in charge, calm, and able to engage in focused efforts to accomplish goals. Children who have been traumatized experience the trauma-related hyperarousal and numbing on a deeply somatic level.

Their hyperarousal is apparent in their inability to relax and in their high degree of irritability.

Single Diagnosis needed for Complex Childhood Trauma History

In recent years, leaders in the treatment of childhood trauma—including Ford, van der Kolk, and Robert Pynoos, M.D., who is director of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN)—have spearheaded a project with colleagues nationwide to support the introduction of a new diagnosis in DSM that more completely accounts for the wide range of childhood developmental trauma.

They say that in the absence of a diagnosis that accurately captures the pervasive nature of disturbances related to early childhood trauma, children tend to receive a hodgepodge of labels for any number of symptoms—PTSD and attention deficit, conduct, and mood disorders—that are treated as separate conditions.

“Approaching each of these problems piecemeal, rather than as expressions of a vast system of internal disorganization, runs the risk of losing sight of the forest in favor of one tree,” said van der Kolk.“ What you call someone has large implications for how you treat someone, even though you may be describing the same phenomenology [using different terms].”

He noted, for instance, that because of the emotional dysregulation that traumatized children frequently display—as well as self-harming behaviors they may adopt as a coping mechanism—they are too often diagnosed with bipolar disorder and treated exclusively with drugs and behavior management.

But van der Kolk and other leaders in the field say that such an approach is an example of how an overly simplified diagnosis can lead to inadequate treatment and a poor outcome.

“Looking at developmental trauma can help us to think more realistically about both the complexity of presenting problems and the depth or extent of clinical services that need to be in play, not only in the consulting room but in the work with parents and teachers,” Marans told Psychiatric News. “It makes a big difference whether you base a diagnosis solely on the presentation of particular symptoms or on a more complex view of how the symptoms are affecting development over time.”

In his article “Developmental Trauma Disorder: A New Rational Diagnosis for Children With Complex Trauma Histories,” in the May 2005 Psychiatric Annals, van der Kolk argued the case for a new diagnostic entity and described implications for treatment.

“The diagnosis of PTSD is not developmentally sensitive and does not adequately describe the effect of exposure to childhood trauma on the developing child,” he wrote. “

Because infants and children who experience multiple forms of abuse often experience developmental delays across a broad spectrum, including cognitive, language, motor, and socialization skills, they tend to display very complex disturbances, with a variety of different, often fluctuating, presentations.”

At the Trauma Center in Boston, van der Kolk said, treatment of severely traumatized children can involve theater groups, yoga, and breathing and sensory integration exercises aimed at enhancing self-regulation. A focus of therapy is improving heart rate variability, which reflects disruption of the body's sympathetic-parasympathetic balance caused by chronic trauma.

In the Psychiatric Annals article, he explained that treatment of chronically traumatized children should focus on three primary areas: establishing the child's capacity to regulate his or her internal states of arousal, learning to negotiate safe interpersonal attachments, and integration and mastery of the body and mind.

Tags:

Whatever happened to this being included in the DSM V?

ReplyDeleteThis post was extremely informative! I am researching the DTD for a paper I'm writing and, though I'm a fan of this proposal, I'm hoping to get alternative perspectives on the issue. I wonder if you are aware of the nature or source of any opposition that this proposal faces? If there isn't much (seems possible based on my inability to find any critiques anywhere on the internet), do you know what potentially holds it back from being included in the DSM-5? Don't know if you'll be able to answer this but if you have any clue as to a direction to point me in I'd greatly appreciate it!

ReplyDelete-thanks!-

Hi Alora,

ReplyDeleteMy guess is that this will not be in the DSM-5, or any future DSM. On the other hand, the DSM may no longer be used in 5-10 years as the field switches to the ICD (which everyone else in the world uses).

Part of it is that (this is my opinion, although there are others critics of the DSM process who are saying the same things) the DSM is largely created by doctors (psychiatrists) and they want the DSM to be a manual of medicine. So if you can't treat it with a drug, they don't want it in the DSM. One need only look at the decision to cut the list of personality disorders in half (from 10 to 5) including the elimination of narcissistic personality disorder.

Complex PTSD has faced the same issues as developmental trauma - not amenable to easy drug treatments, so it gets pushed out.

The DSM-5 committees have posted updates at their site - there might be more information there.

Thanks for your response! I hadn't considered possible objections from the angle of drug treatment before! That's ridiculous to me that so many psychiatrists would object to recognizing the etiology of disorders...especially when this might inform the prescription of medication and expectations for its effectiveness! thanks again!

ReplyDelete