Very interesting article from American Scientist on how little we know about the origins of our everyday behaviors - in short, "form follows failure, not function." The recent book, Kluge: The Haphazard Evolution of the Human Mind, by Gary F. Marcus, looks at this "design" issue in the human brain from an evolutionary adaptation model and finds nature lacking in its design skills.

This Article from Issue: May-June 2010This is a cool argument, though I do not fully agree.

Volume 98, Number 3

Page: 183

DOI: 10.1511/2010.84.183

Designing Minds

How should we explain the origins of novel behaviors?

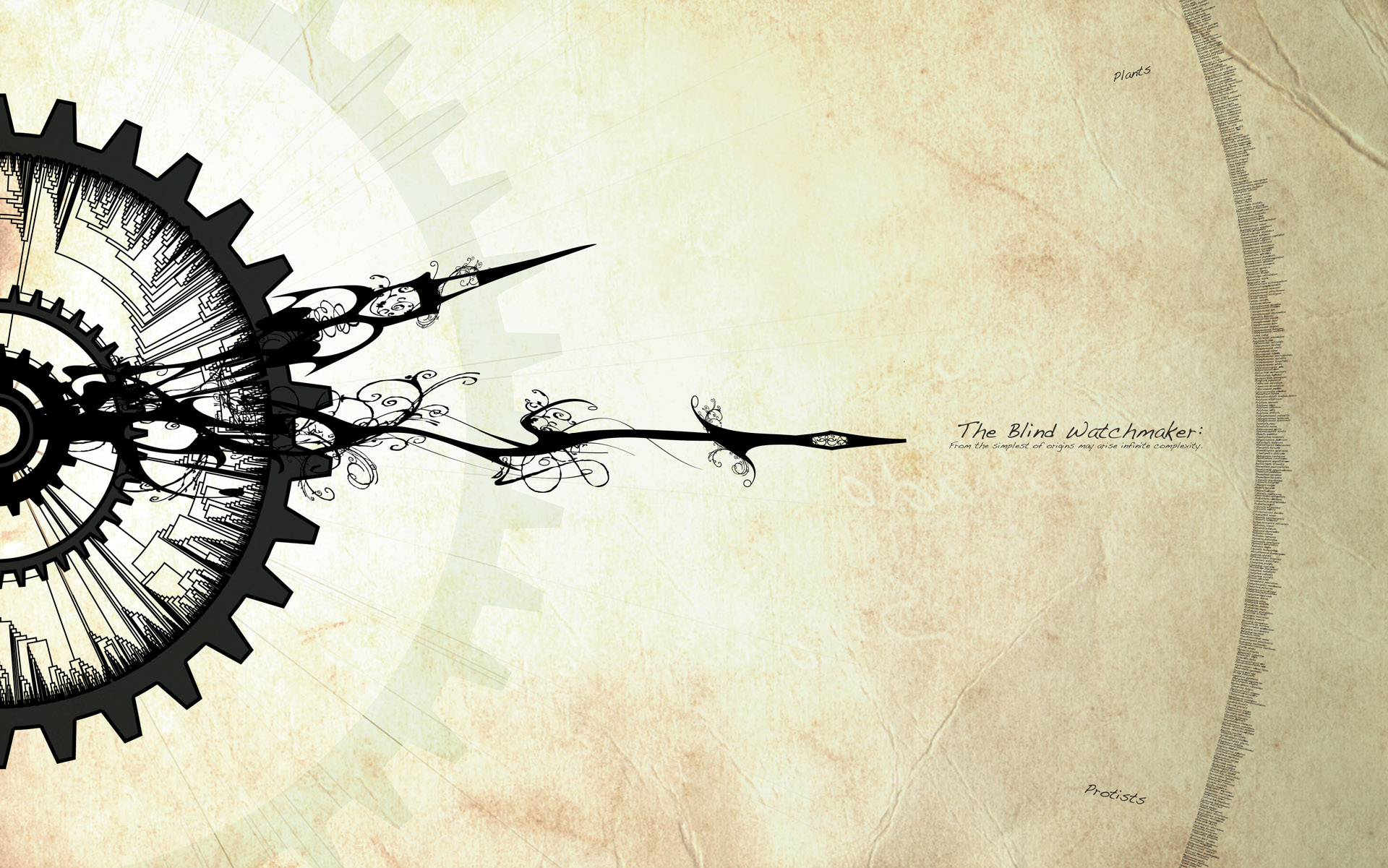

The basic argument of intelligent design was famously set forth in the watchmaker analogy of William Paley in 1802: The complexity and functionality of a watch imply a watchmaker; analogously, the complexity and functionality of living things also imply a designer, albeit one vastly more potent than a mere watchmaker. This argument rests on a simple analogy between the design of human artifacts and the design of natural forms. For the analogy to work, we must first accept that we design our inventions with purpose and foresight. On this point, most evolutionists and creationists agree. What distinguishes these two camps is that, when accounting for the origin of living things, proponents of intelligent design summon a divine creator, whereas evolutionists credit natural selection. Thus, evolutionists share with creationists the same understanding of design; they differ only in how they invoke it.

Discussions of design are prominent in the writings of evolutionists from Darwin to Dawkins. Pondering the implications of his theory of natural selection for Paley’s “old argument of design in nature,” Charles Darwin wrote in his autobiography that we can no longer argue that “the beautiful hinge of a bivalve shell must have been made by an intelligent being, like the hinge of a door by man. There seems to be no more design in the variability of organic beings and in the action of natural selection, than in the course which the wind blows. Everything in nature is the result of fixed laws.” A century later, Richard Dawkins pursued the issue of design and divided the world “into things that look designed (such as birds and airliners) and things that don’t (rocks and mountains).” He further divided those things that look designed into “those that really are designed (submarines and tin openers) and those that aren’t (sharks and hedgehogs).”

What did Dawkins mean when he wrote of things that “really are designed”? In The Blind Watchmaker, he provided a clear answer: “All appearances to the contrary, the only watchmaker in nature is the blind forces of physics….A true watchmaker has foresight: He designs his cogs and springs, and plans their interconnections, with a future purpose in his mind’s eye” [emphasis added].

Such uncritical acceptance of purpose and foresight in human design may well be unwise. After all, do we really know how door hinges and can openers were created? In fact, we may know less about the origins of these everyday contrivances than we know about the origins of bivalve shells, sharks and hedgehogs. By attributing the origins of animals and artifacts to different kinds of designers—one blind, the other intelligent—both Darwin and Dawkins lapse into the same kind of “designer thinking” that ensnared creationists like Paley. Such thinking rests on the familiarity and deceptive simplicity of mentalistic explanations of behavior, as when Dawkins uncritically appeals to the foresight and purpose of the watchmaker rather than entertaining possibly deeper questions about the origins of the watch. He may be giving human designers too much credit.

Form Follows FailureThe engineer Henry Petroski has written extensively and convincingly about our often misguided characterizations of the origins of human inventions. In The Evolution of Useful Things (1993), Petroski argues that artifacts “do not spring fully formed from the mind of some maker but, rather, become shaped and reshaped through the (principally negative) experiences of their users….” In short, form follows failure, not function.

And what about those failures? It is all too easy to forget that the first attempts at flight featured impossible aircraft with flappable wings, man-of-war sails, and box-kite frames. Do we see the origins of today’s jumbo jets in those early, comical failures? Similarly, do we appreciate the knowledge gained by bridge builders from studying the undulating destruction of the Tacoma Narrows Bridge in Washington or, more recently, the wobbling of the Millennium Bridge in London? Do we understand that even the most tragic failures—such as the Hyatt Regency walkway collapse in Kansas City or the Challenger space shuttle explosion—are the consequences of human tinkering on a grand scale? Beginning with the very first glimpse of a problem or an opportunity, such failures—whether large or small, tragic or comic—prompt the fine-tuning and retrofitting that, over time, have shaped even our greatest engineering achievements, from Egyptian pyramids to medieval cathedrals to suspension bridges to spacecraft.

It is through this plodding process that today’s designs—typically instantiated in the form of a detailed blueprint—embody all of the hard, painful, but often unacknowledged lessons of the past. Most of us are ignorant of that history, yet we glibly proclaim that the final products were intelligently designed, thereby perpetuating the myth of the creative moment. We then carry that myth forward and attribute each new artifact to individual insight, creativity and genius. But this myth cannot cheat reality; the failures just keep coming, as most recently illustrated by the massive worldwide recall of Toyota automobiles. As Petroski notes in To Engineer Is Human (1985), despite their mathematically precise understanding of structural materials, engineers still cannot “calculate to obviate the failure of the mind.”

Because of the writings of Darwin, Dawkins and other biologists, many of us are now open to understanding the organic world in evolutionary terms—but are we equally willing to apply such evolutionary thinking to that last bastion of designer intelligence, our minds? Curiously, just as Petroski and others are painstakingly detailing the origins of human inventions, researchers are increasingly invoking unsubstantiated mental processes to explain complex human and animal behaviors.

Insight About Insight

A salient recent example can be found in a report in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in Spring 2009, in which crows were observed to fashion wire into hooks that were then used to retrieve out-of-reach food items. These behaviors have been interpreted by some authors as products of this species’ creativity and insight. In contrast, other scientists have investigated similar “insight” problems in crows, monkeys and other animals; but by focusing on the origins of these behaviors, they have discovered the critical learning experiences, as opposed to forethought, that gave rise to them. Nonetheless, we seem to be in the midst of a resurgence of faith among some scientists that animal behavior can be explained by creativity, insight and other mentalistic concepts. For our part, we remain skeptical about the utility of such groundless explanations. Indeed, we are unconvinced that creativity and insight are proper explanations even for human behavior.

Of course, few people are unnerved when the cognitive prowess of crows or other animals is questioned. Things get stickier when we express similar skepticism about the human mind. Yet as with the invention of human artifacts, we see good reason to doubt the prevailing belief that novel human behaviors—what we might call behavioral inventions—are necessarily the products of a designing mind.

Successful Flop

A celebrated case of human behavioral invention lends credence to our view. Dick Fosbury revolutionized the high jump with a world-record bound of 7 feet, 4 ¼ inches, which earned him a gold medal at the 1968 Olympics. Some might suspect that his innovation—the so-called Fosbury Flop—was designed with purpose and foresight in a single creative moment. In fact, it unfolded over considerable time, beginning in high school when Fosbury used the outmoded “scissors” jump. Urged by his coach to adopt the more sophisticated “straddle,” his lanky body failed to comply with his coach’s wishes. When Fosbury reverted to the “scissors,” he began to lift his hips to reach higher altitude, thereby forcing back his head and shoulders. In this way, the flop evolved, not from design, but from a protracted trial-and-error process that combined repeated effort with the biomechanics of Fosbury’s gangly physique. Here is how Fosbury himself described this process: “I began to lift my hips up and my shoulders went back in reaction to that. At the end of the competition, I had improved my best by 6?, from 5′ 4? to 5′ 10? and even placed third! The next two years in high school, with my curved approach, I began to lead with my shoulder and eventually was going over head first like today’s Floppers.”

Another example of human behavioral invention from the sporting world—this one from thoroughbred racing—further supports our view. A recent report in Science carefully explained how the monkey crouch—the currently dominant racing style, in which the jockey rides poised above the saddle leaning forward—promotes faster racing times. At the expense of a much more strenuous ride for the jockey than the earlier, upright style, the monkey crouch confers measurable biomechanical benefits for the horse. No one has yet suggested that the monkey crouch was designed with purpose and foresight to maximize biomechanical efficiency. So how did it arise?

Some authors have credited two American jockeys with bringing the monkey crouch to England in the late 1800s. An English rider, Harding Cox, may actually have adopted this riding style a bit earlier. Critical to our present considerations, Cox suggested in his memoir the possible benefits that the monkey crouch conferred: “When hunting, I rode very short, and leant well forward in my seat. When racing, I found that by so doing I avoided, to a certain extent, wind pressure, which … is very obvious to the rider. By accentuating this position, I discovered that my mount had the advantage of freer hind leverage. Perhaps that is why I managed to win on animals that had been looked upon as ‘impossibles,’ ‘back numbers,’ rogues and jades.”

Although the authors of the Science report emphasize the biomechanical benefit to the horse of having the jockey rise from the saddle, and they deemphasize the role of decreased wind resistance, Cox’s account provides a key insight into this innovation’s true origins. Specifically, decreased wind resistance may have initially encouraged Cox’s forward adjustment, which allowed his later accentuation of the posture into the fully realized monkey crouch. Like a scaffold that provides a temporary structure for the construction of a building, Cox’s response to wind pressure may have scaffolded his behavioral transition to a novel riding style—one that transformed modern thoroughbred racing.

Inventive behaviors are commonly attributed to creativity, insight or genius, but a far simpler explanation may do. For the Fosbury Flop and the monkey crouch, an elegant and plausible way to understand the origins of novel behaviors can be found in the law of effect, which emerged a century ago from the animal-behavior studies of psychologist Edward Thorndike. The law of effect states that successful behavioral variations are retained and unsuccessful variations are not. Importantly, this positively Darwinian process exists entirely outside the realm of purpose or foresight. If everything in nature is the result of fixed laws, as Darwin himself proposed, then would he not also have marveled at the explanatory power of the law of effect—which was not discovered until several decades after his death—and its compelling parallels with natural selection?

Our prime point here is the importance of the search for origins. Darwin has taught us that the search for the origin of species reveals the action of natural mechanisms that do not require guidance from a creative, intelligent designer. Similarly, Petroski has taught us to look beyond the romance of the iconoclastic inventor and the drama of the creative moment to appreciate the real origins of human artifacts. Petroski’s insight should free evolutionists from their continuing dispute with creationists over where to draw the line between things that really are designed and things that only appear to be designed. Belief in the existence of that false line only serves to obscure the powerful selectionist processes that are at work in producing so many of the world’s creations—both organic and synthetic.

Beyond the concerns of Darwin and Petroski, we see additional fertile ground for reshaping how we think about the origins of behavioral innovations. We have focused here on the Fosbury Flop and the monkey crouch, but we could also have discussed the role of serendipity in scientific discovery or the developmental path by which each of us learns to crawl, walk and run. From our first days of life, we are all inventors who discover by trial and error how our growing bodies work and move. As with organic evolution, the development of behavior is indeed a creative process, but it is one that unfolds without purposeful design.

Tags:

No comments:

Post a Comment