The itch nobody can scratch

A new disease is plaguing thousands, but experts are in conflict over its origins—and whether it exists at all.

Will Storr in Matter

IT BEGAN THE WAY IT SO OFTEN BEGINS, so those that tell of it say: with an explosion of crawling, itching and biting, his skin suddenly alive, roaring, teeming, inhabited. A metropolis of activity on his body.

This is not what fifty-five-year-old IT executives from Birmingham expect to happen to them on fly-drive breaks to New England. But there it was and there he was, in an out-of-town multiscreen cinema in a mall somewhere near Boston, writhing, scratching, rubbing, cursing. His legs, arms, torso — God, it was everywhere. He tried not to disturb his wife and two sons as they gazed up, obliviously, at Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. It must be fleas, he decided. Fleas in the seat.

That night, in his hotel, Paul could not sleep.

“You’re crazy, Dad,” said the boys.

It must be ticks, mites, something like that. But none of the creams worked, nor the sprays. Within days, odd marks began to appear, in the areas where his skin was soft. Red ones. Little round things, raised from his skin. Paul ran his fingertips gently over them. There was something growing inside them, like splinters or spines. He could feel their sharp points catching. Back home, he told his doctor, “I think it’s something strange.”

Paul had tests.

It wasn’t scabies. It wasn’t an allergy or fungus. It wasn’t any of the obvious infestations. Whatever it was, it had a kind of cycle. The creeping and the crawling was the first thing. Then the burrowing and then biting, as if he was being stabbed with compass needles. Then the red marks would come and, inside them, the growing spines.

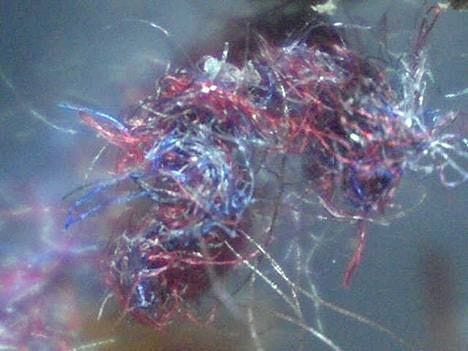

One evening, nearly a year after his first attack, Paul’s wife was soothing his back with surgical spirit when she noticed that the cotton swab had gathered a bizarre blue-black haze from his skin. Paul dressed quickly, drove as fast as he could to Maplin’s, bought a microscope and placed the cotton beneath the lens. He focused. He frowned. He focused again. His mouth dropped open.

Dear God, what were they? Those weird, curling, colored fibers? He opened his laptop and Googled: ‘Fibers. Itch. Sting. Skin.’ And there it was — it must be! All the symptoms fit. He had a disease called Morgellons. A new disease.

According to the website, the fibers were the product of creatures, unknown to science, that breed in the body. Paul felt the strong arms of relief lift the worry away. Everything was answered, the crucial mystery solved. But as he pored gratefully through the information on that laptop screen, he had no idea that Morgellons would actually turn out to be the worst kind of answer imaginable.

Morgellons was named in 2002, by American mom Mary Leitao, after she learned of a similar-sounding (but actually unrelated) condition that was reported in the seventeenth century, in which children sprouted hairs on their backs.

Leitao’s son had been complaining of sores around his mouth and the sensation of ‘bugs’. Using a microscope, she found him to be covered in red, blue, black and white fibers. Since then, experts at Leitao’s Morgellons Research Foundation say they have been contacted by over twelve thousand affected families. Educational and support group The Charles E. Holman Foundation claim there are patients in “every continent except Antarctica.”

Even folk singer Joni Mitchell has been affected, complaining to the LA Times about “this weird incurable disease that seems like it’s from outer space . . . Fibers in a variety of colors protrude out of my skin . . . they cannot be forensically identified as animal, vegetable or mineral. Morgellons is a slow, unpredictable killer — a terrorist disease. It will blow up one of your organs, leaving you in bed for a year.”

Since Leitao began drawing attention to the problem, thousands of sufferers in the US have written to members of Congress, demanding action. In response, more than forty senators, including Hillary Clinton, John McCain and a pre-presidential Barack Obama, pressured the government agency the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), to investigate. In 2008, the CDC established a special task force in collaboration with the US Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, with an initial budget of one million dollars. At a 2008 press conference, held to update the media on the agreed protocol for a scientific study, principal investigator Dr Michele Pearson admitted, “We don’t know what it is.”

So, it is new and it is frightening and it is profoundly peculiar. But if you were to seek the view of the medical establishment, you would find the strangest fact of all about the disease.

Morgellons doesn’t exist.

I have met Paul in a Tudor-fronted coaching inn, in a comfy executive suburb west of Birmingham. He arrived in a black Audi with leather seats, his suit jacket hanging on a hook over a rear window. There is chill-out music, a wood-fired pizza oven and, in the sunny garden, a flock of cyclists supping soft drinks from ice-clinking glasses. Paul is showing me pictures that he has collected of his fibers. A grim parade of jpegs flicks past on his screen — sores and scabs and nasal hairs, all magnified by a factor of two hundred. In each photo, a tiny colored fiber on or in his skin.

“Is it an excrement?” he asks. “A byproduct? A structure they live in?” A waitress passes with a bowl of salad as he gestures towards an oozing wound. “Is it a breathing pipe?” He shakes his head. “It’s just like something from science fiction. It’s something that you’d see in a movie or in a book on aliens from another planet. It’s out of this world.”

I nod and scratch my neck while Paul absentmindedly digs his nails into a lesion just below the hem of his khaki shorts. They visibly pepper his legs and arms — little red welts, some dulled to a waxy maroon, older ones now just plasticky-white scar tissue.

Paul has seen an array of experts — allergy doctors, tropical-and infectious-disease specialists, dermatologists. He has visited his doctor more times than he can remember. None of them have given him an answer that satisfies him, or offered an end to the itching. His most recent attempt was at a local teaching hospital. “I thought, Teaching hospital! They might want to do a study on me. Last week, I took them some samples of the fibers on a piece of cotton wool. But they discharged me. They said there was nothing they could do.”

Everywhere Paul goes, he carries a pot of alcohol hand-gel, which he has spiked with a traditional Middle Eastern parasite-killer called neem oil. In between his four daily showers, he steam cleans his clothes. The stress of it all leaves him exhausted, short-tempered. He has difficulty concentrating; applying himself at work. “It affects my performance a bit,” he says.

“What does your wife think?” I ask.

His voice cracks.

“Frustrated,” he says. “Sick of me being depressed and irritated. She wants her normal life back. And sometimes, without any progress coming along, I get depressed. Very depressed.”

“When was your lowest moment?”

He breaks eye contact.

“I don’t want to go into that.”He stares into his half of ale, scratches his wrist and says, eventually, “Pretty much feeling like ending it. Thinking, could I go through with it? Probably. It’s associated with the times the medical profession have dismissed me. It’s just — I can’t see myself living forever with this.”

“Have you mentioned these thoughts to your doctor?”

“No, because talking about suic—” He stops himself. “Things like that . . .” Another pause. “Well, it adds a mental angle.”

Paul is referring to the pathology that clinicians and Skeptics alike claim is actually at the root of Morgellons. They say that what people like him are really suffering from is a form of psychosis called delusions of parasitosis, or DOP. He is, in other words, crazy.

It is a view typified by academics such as Jeffrey Meffert, an associate professor of dermatology at the University of Texas in San Antonio, who has created a special presentation devoted to debunking Morgellons that he regularly presents to doctors and who told the Washington Post, “Any fibers that I have ever been presented with by one of my patients have always been textile fibers.”

It is thought that it is spread, not by otherworldy creatures but by the Internet. As Dr Mary Seeman, Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Toronto, explained to the New York Times, “When a person has something bothering him these days, the first thing he does is go online.”

Dr Steven Novella of The Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe agrees: “It is a combination of a cultural phenomenon spreading mostly online, giving specific manifestation to an underlying psychological condition. I am willing to be convinced that there is a biological process going on, but so far no compelling evidence to support this hypothesis has been put forward.”

But Paul is convinced. “It is absolutely a physical condition,” he insists. “I mean, look!”

Indeed, the evidence of his jpegs does seem undeniable. Much thinner than his body hair, the fibers bask expansively in craterous sores, hide deep in trench-like wrinkles and peer tentatively from follicles. They are indisputably there. Morgellons seems to represent a mystery even deeper than that of homeopathy. Its adherents offer physical evidence. Just for once, I wonder, perhaps the Skeptics might turn out to be wrong.

In an attempt to find out, I am traveling to the fourth Annual Morgellons Conference in Austin, Texas, to meet a molecular biologist who doesn’t believe the medical consensus. Rather, the forensic tests he has commissioned on the fibers point to something altogether more alien.

IN THE SPRING OF 2005, Randy Wymore, an associate professor of pharmacology at Oklahoma State University, accidentally stumbled across a report about Morgellons.

Reading about the fibers that patients believed were the byproduct of some weird parasite, but which were typically dismissed by disbelieving dermatologists as textile fragments, he thought, “But this should be easy to figure out.” He emailed sufferers, requesting samples, then compared them to bits of cotton and nylon and carpets and curtains that he had found about the place. When he peered down the microscope’s dark tunnel for the first time, he got a shock. The Morgellons fibers looked utterly different.

Wymore arranged for specialist fiber analysts at the Tulsa Police Department’s forensic laboratory to have a look. Twenty seconds into their tests, Wymore heard a detective with 28 years’ experience of doing exactly this sort of work murmur, “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like this.” As the day wound on, they discovered that the Morgellons samples didn’t match any of the 800 fibers they had on their database, nor the 85,000 known organic compounds. He heated one fiber to 600°C and was astonished to find that it didn’t burn. By the day’s end, Wymore had concluded, “There’s something real going on here. Something that we don’t understand at all.”

In downtime from teaching, Wymore still works on the mystery. In 2011, he approached a number of commercial laboratories and attempted to hire them to tease apart the elements which make the fibers up. But the moment they discovered the job was related to Morgellons, firm after firm backed out. Finally, Wymore found a laboratory that was prepared to take the work. Their initial analyses are now in, but the conclusions unannounced. More than anything else, it is this that I am hoping to hear about over the coming days.

It all begins an hour south of Austin, Texas, in the lobby of the Westoak Woods Church convention center. Morgellons sufferers are gathering around the Continental breakfast buffet. From the UK, Spain, Germany, Mexico and 22 US states, they dig greedily into the sticky array — Krispie Treats, Strawberry Cheese-flavor Danish pastries, and Mrs Spunkmeyer blueberry muffins — as loose threads of conversation rise from the hubbub:

“I mix Vaseline with sulfur and cover my entire body to suffocate them”; “The more you try to prove you’re not crazy, the more crazy they think you are”; “The whole medical community is part of this. I wouldn’t say it’s a conspiracy but…” At a nearby trestle table, a man sells pots of “Mor Gone gel” (“Until There Is A Cure… There Is Mor Gone”).

Many of the attendees that are moving slowly towards the conference hall will have been diagnosed with DOP, a subject that possesses a day-one speaker, paediatrician Greg Smith, with a fury that bounces him about the stage, all eyes and spit and jabbing fingers.

“Excuse me, people!” he says. “This is morally and ethically wrong! So let me make a political statement, boys and girls.”

He dramatically pulls off his jumper, to reveal a T-shirt: ‘DOP’ with a red line through it.

“No more!” he shouts above the whoops and applause. “No more!”

Out in the car park, Smith tells me that he has been a sufferer since 2004. “I put a sweatshirt I’d been wearing in the garden over my arm and there was this intense burning, sticking sensation. I thought it was cactus spines. I began picking to get them out, but it wasn’t long before it was all over my body.” He describes “almost an obsession. You just can’t stop picking. You feel the sensation of something that’s trying to come out of your skin. You’ve just got to get in there. And there’s this sense of incredible release when you get something out of it.”

“What are they?” I ask.“Little particles and things,” he says, his eyes shining. “You feel the sensation of something that’s trying to come out of your skin.” He is pacing back and forth now. He is becoming breathless. “You feel that. And when you try to start picking, sometimes it’s a little fiber, sometimes it’s a little hard lump, sometimes little black specks or pearl-like objects that are round and maybe half a millimeter across. When it comes out, you feel instant relief. It’s something in all my experience that I had never heard of. It made no sense. But I saw it over and over again.”

Sometimes, these fibers can behave in ways that Smith describes as “bizarre.” He tells me of one occasion in which he felt a sharp pain in his eye. “I took off my glasses and looked in the mirror,” he says. “And there was a fiber there. It was white and really, really tiny. I was trying to get it out with my finger, and all of a sudden it moved across the surface of my eye and tried to dig in. I got tweezers and started to pick the thing out of eyeball. I was in terrible pain.”

I am horrified.

“Did it bleed?”

“I’ve still got the scar,” he nods. “When I went to the emergency room and told the story of what had been going on — they called a psychiatrist in! I was like, “Wait a minute, what the heck is going on here?” Fortunately, he didn’t commit me and after another consultation with him he became convinced I was not crazy.”

“So, it was a Morgellons fiber?” I say. “And it moved?”

‘Of course it was a fiber!’ he says. ‘It honest-to-God moved.’

Smith tells me that a Morgellons patient who finds unusual fibers in their skin will typically bring a sample to show their doctor. But when they do this, they’re unknowingly falling into a terrible trap. It is a behavior that is known among medical professionals as ‘the matchbox sign’ and it is used as evidence against them, to prove that they are mentally ill.

“The matchbox sign was first described in about 1930,” he says. “They say it’s an indicator that you have DOP. This is something that infuriates me. It has absolutely zero relevance to anything.”

Back in the UK, of course, Paul received his diagnosis of DOP after taking fiber-smeared cotton to his dermatologist. I tell Greg Smith that, were I to find unexplained particles in my skin, I would probably do exactly the same.

“Of course!” he says. “It’s what anyone would do if they had any sense at all. But the dermatologist will stand ten feet away and diagnose you as delusional.”

“But surely they can see the fibers?”

“They can if they look. But they will not look!”

“And if you try to show them the fibers, that makes you delusional?”

“You’re crazy! You brought this in for them to look at? First step — bang.”

“But this is madness!” I say.

“It’s total madness! It’s inexcusable. Unconscionable.”

We speak about the CDC study. Like almost everyone here, Smith is suspicious of it. There is a widespread acceptance at this conference that the American authorities have already decided that Morgellons is psychological and — in classic hominin style — are merely looking for evidence to reinforce their hunch. Both Smith and Randy Wymore, the molecular biologist who arranged the forensic examination in Tulsa, have repeatedly offered to assist in finding patients, and have been ignored.

“Have you heard of the phrase “Garbage In Garbage Out”?” he says. “It doesn’t matter what conclusion that study comes to, even if it is totally favorable to the Morgellons community. It’s not well designed. It’s trash.”

As he speaks I notice Smith’s exposed skin shows a waxy galaxy of scars. Although he still itches, all of his lesions appear to have healed. It is a remarkable thing. Skeptics believe that Morgellons sores are not made by burrowing parasites but by obsessive scratchers eroding the skin away. If Smith is correct, though, and the creatures are responsible for the sores, how has he managed to stop those creatures creating them?

“I absolutely positively stopped picking,” he tells me.

“And that was it?”

“Sure,” he replies, shrugging somewhat bemusedly, as if what he has just said doesn’t run counter to everything that he is supposed to believe.

That evening, the Morgellons sufferers are enjoying a celebratory enchilada buffet at a suburban Mexican restaurant. Over the lukewarm feast, I have a long conversation with a British conventioneer — a midwife from Ramsgate named Margot.

Earlier in the day, when I first met Margot, she said something that has been loitering in my mind ever since, wanting my attention but not quite sure why or what it is doing there. We were at a cafe, waiting for the man to pass us our change and our lunch. He dropped the coins into our hands and turned to wrap our sandwiches. As he did so, Margot sighed theatrically and gave me a look as if to say, ‘Unbelievable! Did you see that?!’

I had no idea what she meant.

She rolled her eyes and explained, “He touches the money, then he touches our food…”

Tonight, Margot describes a scene which ends up proving no less memorable: her, sat naked in a bath full of bleach, behind a locked door, wearing times-three magnification spectacles, holding a magnifying glass and a nit comb, scraping her face onto sticky office labels and examining the ‘black specks’ that were falling out. Perhaps sensing my reaction, she tries to reassure me: “I was just being analytical,” she insists.

When bathing in bleach all night didn’t help, Margot brought her dermatologist samples of her sticky labels. Shaking his head, he told her, “I can’t tell you how many people bring me specimens of lint and black specks in matchboxes.” She was diagnosed with DOP. Her employment was terminated. “I’m a midwife,” she says, in her defense. “I take urine and blood samples — specimens. So I was taking them a specimen. And that’s what wrecked my life and career.”

As I am talking with Margot, I notice Randy Wymore, the molecular biologist I have been desperate to speak with, sitting at a nearby table. He is a slim, neat man wearing a charcoal shirt, orange tie and tidily squared goatee. When I sit with him, I find him to be incorrigibly bright, light and happy, even when delivering wholly discouraging news.

The first two samples that Wymore sent to the laboratory were not from Morgellons patients, but test fibers gathered from a barn and a cotton bud and then some debris from the filter in an air-conditioning unit. When the technicians correctly identified what they were, Wymore felt confident enough to submit the real things. And, so far, he says, ‘We have not yet exactly replicated the exact results of the forensics people in Tulsa.’

Indeed, the laboratory has found Wymore’s various Morgellons fibers to be: nylon; cotton; a blonde human hair; a fungal residue; a rodent hair; and down, likely from geese or ducks.

“That’s disappointing,” I say.

He leans his head to one side and smiles.

“It is for the most part disappointing,” he says. “But there was a bunch of cellulose that didn’t make sense on one. And another was unknown.”

“Really?”

“Well, they said it was a ‘big fungal fiber.’ But they weren’t completely convinced.”

Image courtesy of Charles E Holman Foundation

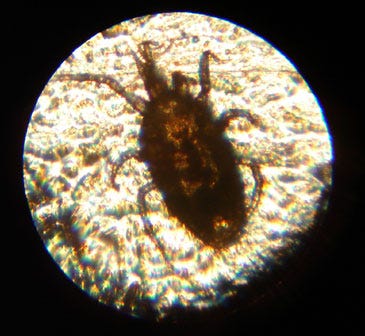

Image courtesy of Charles E Holman Foundation

The next day, nursing practitioner Dr Ginger Savely — who claims to have treated over 500 Morgellons patients — leads an informal discussion in the hotel conference room. Around large circular tables they sit: the oozing and the itchy, the dismissed and the angry. “I’ve seen a fiber go into my glasses,” says one. “I’ve seen one burrow into a pad”; “One of my doctors thinks it’s nanotechnology”; “Check your clothing from China for nematodes”; “Never put your suitcase on the floor of a train”; “I was attacked by a swarm of some type of tiny wasps that seemed to inject parts of their bodies under my skin.”

I am writing the words ‘tiny wasps’ into my notepad when a furious woman with a terrifying itch-scar on her jaw says, “I have Erin Brockovich’s lawyer’s number in my purse. Don’t you think I’m not going to use it.”

“But who are you going to sue?” asks a frail elderly lady two tables away.

We all look expectantly at her. There is a moment of tense quiet.

“I don’t know,” she says.

In a far corner, a woman with a round plaster on a dry, dusty, pinkly scrubbed cheek weeps gently.

Ten minutes later, I am alone in the lobby, attempting to focus my thoughts. My task here is straightforward. Has Paul been failed by his medics, or is he crazy? Are these people infested with uncommon parasites or uncommon beliefs? Over at the reception desk, a conventioneer is complaining loudly, hammering her finger on the counter.

“It’s disgusting! Bugs! In. The. Bed. I’ve already been in two rooms. I had to drive to Walmart to buy fresh linen at 5 a.m. There’s this white stuff all over the counter…”

When she has gone, I approach the desk and ask the receptionist if the weekend has seen a surge in complaints about cleanliness.

“Oh yeah.” She nods towards the conference room. “And they’re all coming from those people.” She leans forward and whispers conspiratorially. “I think it’s part of their condition.”

Satisfied, I retire to the lobby to await my allotted chat with Dr Savely.

“So, what do you think,” I ask her, “about these tiny wasps?”

“Hmmm, no,” she says. “But I haven’t totally dismissed the whole genetically modified organisms thing. Something may have gone amuck.”

“Nanotechnology?” I ask. “Some defense experiment gone awry?”

“If something like that went wrong and got out to the public…”

I decide to confess to Dr Savely my conclusion: that these people are, in fact, crazy.

“These people are not crazy,” she insists. “They’re good, solid people who have been dealt a bad lot.”

A woman approaches the vending machine behind the doctor. Between her palm and the top of her walking stick, there is a layer of tissue paper. We sit there as she creaks slowly past us.

“There’s definitely an element of craziness here,” I say.

“But I truly believe it’s understandable,” she says. “For people to say you’re delusional is very anxiety-provoking. Then they get depressed. Who wouldn’t? Hello! The next stage is usually an obsessive-compulsive thing — paying attention to the body in great detail. But, again, I feel this is understandable in the circumstances.”

Not wholly convinced, I slip back into the conference room, where Margot is using her $1,100 WiFi iPad telescope to examine herself. Suddenly, I have an idea.

“Can I have a go?”

Pushing the lens into my palm, I immediately see a fiber. The group falls into a hush. “Did you clean your hand?” asks Margot. She fetches an anti-bacterial wet-wipe. I scrub and try again. I find an even bigger fiber. I wipe for a second time.

And find another one. Margot looks up at me with wet, sorry eyes. “Are you worried?” She puts a kind, comforting hand on my arm. “Oh, don’t be worried, Will. I’m sure you haven’t got it.”

Back in London, I find a 2008 paper on Morgellons in a journal called Dermatologic Therapy. It describes Morgellons patients picking “at their skin continuously in order to “extract” an organism”; “obsessive cleaning rituals, showering often” and individuals going “to many physicians, such as infectious disease specialists and dermatologists” — all behaviors that are “consistent with DOP” and also consistent with Paul. (For treatment, the authors recommend prescribing a benign anti-parasitic ointment to build trust, then topping it up with an anti-psychotic.) After finding fibers on my own hand, I am satisfied that Morgellons is some 21 century genre of OCD that’s spread like an Internet meme, and the fibers are — just as Dr Wymore’s labs are reporting — particles of everyday, miscellaneous stuff: cotton, human hair, rat hair and so on.

I am finalizing my research when I decide to check one final point that has been niggling maddeningly. The itch. Both Paul and Greg’s Morgellons began with an explosion of it. It is even affecting me: the night following my meeting with Paul, I couldn’t sleep for itching. I had two showers before bed and another in the morning. All through the convention — even as I write these words — I am tormented; driven to senseless scratching.

Why is itch so infectious?

For background, I contact Dr Anne Louise Oaklander, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School and probably the only neurologist in the world to specialize in itch. I email her describing Morgellons, carefully acknowledging that it is some form of DOP. But when we speak, Dr Oaklander tells me she knows all about Morgellons already. And then she says something that stuns me.

“In my experience, Morgellons patients are doing the best they can to make sense of symptoms that are real. These people have been maltreated by the medical establishment. And you’re very welcome to quote me on that. They’re suffering from a chronic itch disorder that’s undiagnosed.”

To understand all this, it is first necessary to grasp some remarkable facts about itch. In 1987 a team of German researchers found itch wasn’t simply the weak form of pain it had always been assumed to be. Rather, they concluded that itch has its own separate and dedicated network of nerves. And remarkably sensitive things they turned out to be: whereas a pain nerve has sensory jurisdiction of roughly a millimeter, an itch nerve can pick up disturbances on the skin over seventy-five millimeters away.

Dr Oaklander surmises that itch evolved as a way for humans to automatically rid themselves of dangerous insects. When a mosquito lands on our arm and it tickles, this sensation is not, as you might assume, the straightforward feeling of its legs pressing on our skin. That crawling, grubbing, tickling sensation is, in fact, a neurological alarm system that is wailing madly, begging for a scratch.

This alarm system can go wrong for a variety of reasons — shingles, sciatica, spinal-cord tumors or lesions, to name a few. It can ring suddenly, severely and without anything touching the skin. This, Oaklander believes, is what is happening to Morgellons patients.

“That they have insects on them is a very reasonable conclusion to reach, because, to them, it feels no different to how it would if there were insects on them. To your brain, it’s exactly the same. So you need to look at what’s going on with their nerves. Unfortunately, what can happen is a dermatologist fails to find an explanation and jumps to a psychiatric one.”

Of the obsessive investigations that Morgellons patients conduct on themselves, Oaklander says: “When you feel an itch, what do you do? You look. That’s the natural response. They may become fixated on the insect explanation for lack of a better one.”

But, she adds, that is not to say there aren’t some patients whose major problem is psychiatric. Others still might suffer delusions in addition to their undiagnosed neuropathic illness. Nevertheless, “It’s not up to some primary-care physician to conclude that a patient has a major psychiatric disorder.”

If Oaklander turns out to be correct, it makes sense of the fact that Greg Smith’s lesions healed when he stopped scratching. If the fibers are picked up by the environment, it explains how I found them on my hand. And if Morgellons is not actually a disease, but rather a witchbag of symptoms that might all have nerve-related maladies as its source, it squares something that Dr Savely said she is “constantly perplexed” about: “When I find a treatment that helps one person, it doesn’t help the next at all. Every patient is a whole new ballgame.”

Thrilled at this development, I phone Paul and explain the itch-nerve theory. But he doesn’t seem very excited.

“I can’t see how that relates to my condition,” he sighs. “I’ve got marks on my back that I can’t even reach. I’ve not created those by scratching.”

It is a good point, perhaps, but one that I quietly dismiss. It now seems so likely that Paul is either delusional, or has some undiagnosed itch disorder, that I judge that he is merely looking for reasons not to believe this elegant and compelling solution.

Weeks later, I receive an unexpected email from a stranger in east London. Nick Mann has heard about my research into Morgellons and he wonders if I might be curious to hear about his experiences. When I arrive at his house, on a warm Tuesday night, and settle in his small kitchen with a mug of tea, I am doubting the wisdom of my visit. Probably, I think, I am wasting my time.

But Nick doesn’t appear to be the kind of conspiracy-fixated, talking-too-fast, fiddling-with-their-fingers individual who usually gets in touch. Rather, he is a calm and friendly father of two who, he tells me, went for a walk a couple of years ago in the grounds of Abney Park Cemetery, just down the road from his home, when something unsavory took place. It had been a sunny day and he had been wearing shorts and sandals. That evening, his legs began itching. Marks sprang up on his body. ‘I was convinced something was on me,’ he tells me. ‘Something digging into my skin. Burrowing.’

Over the coming days, lesions began to open up on his skin. Running his fingertips over them, he could feel something inside: spines or fibers. He stripped naked in his kitchen and tried to dig one out.

“I stood there for three or four hours, waiting for one to bite,” he says. “As soon as it did, I went for it with a hypodermic needle. There was one on my nipple.” He pales slightly. “You know, I can’t get that out of my head. It was so painful. I dug the needle in and felt it flicking against something that wasn’t me. And I just carried on digging and scooping.” He carried on like this for nearly four hours. “At one point my wife came in and saw blood dripping down from my leg and scrotum.”

By the end of the day, Nick had dug three of the ‘things’ from his body. They were so small, he says, “You could only see them when they moved.” Tipping them from a Rizla paper into a specimen jar, he showed his wife, Karen. She peered into the pot. She looked worriedly at her husband. Karen could see nothing.

I put my pen down and rub my brow. Poor Nick Mann, I think. Just like Greg Smith, madly attacking his own body, trying to remove bits of fluff. And just like Paul — so convinced by the illusion of his own itch response that he became fixated on the fantasy that he had been invaded by invisible monsters. To get some general sense of how unstable this man could turn out to be, I try to discover a bit more about him.

“What did you say you did for a living?” I ask.

“I’m a GP,” he says.

I sit up. “You’re a GP?”

“Yes,” he says, brightly. “I’m a doctor. A GP. At a practice in Hackney.”

“Right,” I say. “Okay. Right. So then what happened?”

“I took the three mites I’d caught to the Homerton Hospital in east London,” he says. “A technician there mounted one on a slide, put it under a microscope and said “Beautiful.” Everyone gathered around saying, “Ooh, look at that.” They had no idea what it was. They sent it over to the Natural History Museum, who identified it within a day. It was a tropical rat mite. What they do is go in through the hair follicles and find a blood vessel at the bottom. That’s where they sit and that’s what the fibers are — their legs folded back.”

It is astonishing. It seems to explain it all — the sudden itch, the fibers, even the lesions in unscratchable places. I discuss with Nick the sorry experiences that Paul had trying to get anyone to take him seriously. Nick admits that he was only able to have his samples examined by experts because he was acting as his own doctor. And if that hadn’t happened, he says, “I would have received exactly the same treatment that he did. Delusions of parasitosis.”

“Paul had the impression that his doctors were working from a kind of checklist,” I say, “and if his symptoms weren’t on it, he was just dismissed as crazy.”

“I’m afraid that’s true,” says Nick. “If none of the medical models fit, they’re dismissed. The immediate conclusion is “medically unexplained symptom”, which is a euphemism for nuts. It’s a sad indictment of my own profession but I’ve experienced it first-hand. There used to be a culture of getting to the bottom of the problem. There isn’t that now. I find that really sad. And the idea that people with Morgellons are nutty — I really did nearly go mad with the itch. It was disturbing my sleep, there was barely a minute where I wasn’t having to scratch or resist the urge to scratch. It’s this constant feeling of being infested. It freaked me out.”

As for the weird reasons that patients come up with for their condition — the nanotechnology, the tiny wasps — Nick is unsurprised. “Of course, you look for answers, don’t you?” he says. “We need to find explanations for things.”

WE NEED EXPLANATIONS. We need certainty. And certainty is precisely what I have been seeking over the last few weeks. Are Morgellons sufferers mad? Are they sane? Are they the one? Or the other? I never considered the possibility that they might be both. And, in this, I wonder if I can detect another clue, another soft point in our faulty thinking about beliefs and who we are.

This compulsion to separate everyone into absolute types is the first lesson of Christianity that I can remember learning: kind people go to heaven, unkind people go to hell. There will come a day of judgment and that judgment will be simple, sliced, clean, merciless. In boyhood, the law of the playground dictates that you mentally divide your cohorts into people that you like and people that you don’t — in-groups and out. This doesn’t change much in adulthood. The Skeptics that I met in Manchester thrived on this kind of binary division — and the combative homeopaths did, too. They both told their story, and cast each other as villain. We are a tribal animal. It is who we are and it is how we are.

The urge is to reduce others to simplified positions. We define what they are, and then use these definitions as weapons of a war. Nobody enjoys the restless unpleasantness of doubt. It is uncomfortable, floating between poles, being pulled by invisible forces towards one or the other. We need definitions. We need decisions. We need finality if we are to heal the dissonance.

When my father told me that I had misunderstood faith — that it was not a matter of certainty, but a journey — I was instinctively hostile to the idea. Perhaps it suited me better to think that Christians are foolishly convinced by childish beliefs; that they are stupid. It is a reassuring story that I told myself because, according to the models of my brain, Christians are Bad.

Journalism, too, encourages just this kind of certainty. Facts, assessed and checked. Liars exposed, truth-tellers elevated. Good guys and bad guys. The satisfaction of firm conclusions, of nuance erased, of reality tamed. In my younger years, I was driven to the ends of my own sanity by the desire for this form of truth — an unthreatening, finished article that is cauterized and stitched and does not bleed. Does she love me? Is she faithful? Will she love me next week? Next year? Did she love him more? Does she desire him more? Will we stay in love for ever?

In my mid-twenties, I attended weekly group therapy sessions in north London with people who were much older than me. One evening, a woman in her mid-forties was talking contemptuously about her father, a university lecturer who, she said, had ‘a crush’ on one of his teenage students. I was scandalized.

“But he’s married!” I said.

She looked baffled. What was my point?

“I mean, doesn’t he love your mum any more?” I said. “Are they getting a divorce?”

The adults around me shared a moment. Glances were exchanged. Sniggers were muted. As I write this, I can tell you that the shame is still alive. I can feel it slithering out from underneath the memory and into my skin.

I used to hold a fierce belief in binary love, of the kind that is promised in music, film and literature. You are in love, or you are not. They were absolute modes of being, like Christian or non-Christian, right or wrong, sane or insane. Today, my marriage is happy because I understand that true love is a mess. It is like my father’s belief in God: a journey, sometimes blissful, often fraught. It is not the ultimate goal that was promised by all those pop songs. It lacks the promise of certainty. But it is its very difficulties that give love its value. If you didn’t have to fight for it — if it was just there, reliable, steady, ever-present, like a cardboard box over your head — what would be its worth?

I used to expect love to be solid, sure, overpowering, decided. That is how we declare ourselves. When we get married, we promise faithfulness for ever. When priests talk about God, they say, “He exists.” When the Skeptics talk about homeopathy, they say, “There is no evidence.” When the medical establishment talk about Swami Ramdev’s pranayama, they say, “It doesn’t work”; when they judge Morgellons sufferers, they say, “They are delusional.”

But what if pranayama works like homeopathy works, by brilliantly triggering various powerful placebo effects? What if these Morgellons sufferers are crazy, but they have been driven to these ends by itching caused by a variety of undiagnosed conditions and rejection by lazy doctors?

As I leave the home of Dr Mann, he kindly offers to see Paul so that he can check if his is an infestation of tropical rat mite. After their meeting, a few weeks later, Nick emails me to say that he found no evidence of it, but that “he’s certainly not delusional.” He sends some fiber pictures and one of Paul’s videos to the experts at the Natural History Museum. They reply, “It is our opinion that the fiber is a fabric fiber and it is only its curvature, and consequent variation in focus, that makes it appear to be arising from under the skin. The specimen in the video does look like a mite. It is not clear enough to be certain, but the most likely candidate is a member of the suborder Astigmata, for example, a species of the family Acaridae or Glycyphagidae. These mites are typically found in stored foods, but also occur in house dust.”

Theirs is a conclusion that will be echoed when the CDC study is finally published.

“No parasites or mycobacteria were detected,” it reports. “Most materials collected from participants’ skin were composed of cellulose, likely of cotton origin. No common underlying medical condition or infectious source was identified, similar to more commonly recognized conditions such as delusional infestation.”

Commenting on the work, Steven Novella writes, “The evidence strongly suggests that a psychological cause of Morgellons is most likely, and there is no case to be made for any other alternative . . . It is entirely consistent with delusional parasitosis.”

And Paul is back where he began.

The last time I speak with him, he sighs deeply down the phone.

“Are you all right?” I ask.

“Pretty crap actually. I’ve been forced out of my job. They said it’s based on my “engagement level” and that’s down to the lack of energy I’ve got at work. I can’t sign myself off sick because Morgellons is not a diagnosis. There’s no legitimate reason for me not to be operating at full speed. But, you know, I’m a fighter. I’m trying to rally against it but it’s . . . quite upsetting, really.”

“How are you coping?”

“Well . . . lurching along the parapet of depression, I suppose. But I’m all right. You can put another line in your book — my job is another thing that has been destroyed by this disease. And all because Morgellons isn’t supposed to exist.”

//.

This is an excerpt from The Unpersuadables: Adventures With The Enemies of Science by Will Storr. If you’d like to purchase the entire book, it’s available on Amazon.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Pages

▼

Sunday, March 16, 2014

The Itch Nobody Can Scratch - Disease or Psychosis?

In this lengthy by riveting article from Matter, Will Storr investigates morgellons, a syndrome that is either a terribly infectious disease involving itching and lesions, or it is a form of psychosis called delusions of parasitosis (DOP). Storr is the author of The Unpersuadables: Adventures with the Enemies of Science (2014), from which this is an excerpt.

No comments:

Post a Comment