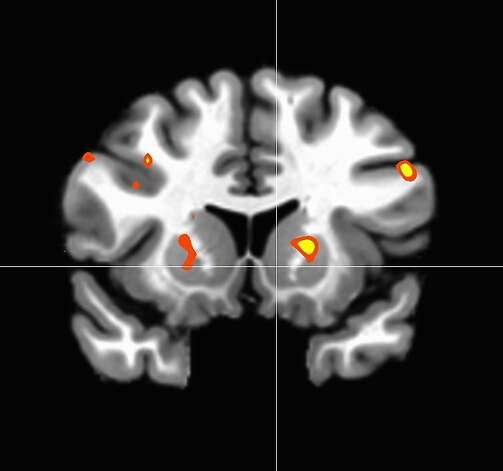

A brain scan of a monk actively extending compassion shows activity in

the striatum, an area of the brain associated with reward processing.

Photo: SPAN Lab, Stanford University

/ SF

It's always cool to see more research on meditative states and brain function - but we need to be a little more careful than we have been with brain imaging studies. We see associations and correlations - at best - but there are always other brain regions active. Just as important as seeing which brain areas or circuits are active is seeing which ones are not active - dampening has a lot to do with functional experience as well.

Stanford studies monks' meditation, compassion

Meredith May

Saturday, July 7, 2012

Stanford neuroeconomist Brian Knutson is an expert in the pleasure center of the brain that works in tandem with our financial decisions - the biology behind why we bypass the kitchen coffeemaker to buy the $4 Starbucks coffee every day.He can hook you up to a brain scanner, take you on a simulated shopping spree and tell by looking at your nucleus accumbens - an area deep inside your brain associated with fight, flight, eating and fornicating - how you process risk and reward, whether you're a spendthrift or a tightwad.So when his colleagues saw him putting Tibetan Buddhist monks and nuns into the MRI machine in the basement of the Stanford psychology building, he drew a few double-takes.Knutson is still interested in the nucleus accumbens, which receives a dopamine hit when a person anticipates something pleasant, like winning at blackjack.Only now he wants to know if the same area of the brain can light up for altruistic reasons. Can extending compassion to another person look the same in the brain as anticipating something good for oneself? And who better to test than Tibetan monks, who have spent their lives pursuing a state of selfless nonattachment?Meditation science

The "monk study" at Stanford is part of an emerging field of meditation science that has taken off in the last decade with advancements in brain image technology, and popular interest."There are many neuroscientists out there looking at mindfulness, but not a lot who are studying compassion," Knutson said. "The Buddhist view of the world can provide some potentially interesting information about the subcortical reward circuits involved in motivation."By looking at expert meditators, neuroscientists hope to get a better picture of what compassion looks like in the brain. Does a monk's brain behave differently than another person's brain when the two are both extending compassion? Is selflessness innate, or can it be learned?Looking to the future, neuroscientists wonder whether compassion can be neurologically isolated, if one day it could be harnessed to help people overcome depression, to settle children with hyperactivity, or even to rewire a psychopath."Right now we're trying to first develop the measurement of compassion, so then one day we can develop the science around it," Knutson said.Stress reduction

Thirty years ago, medical Professor Jon Kabat-Zinn used meditation as the basis for his revolutionary "Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program." He put people with chronic pain and depression through a six-week meditation practice in the basement of the University of Massachusetts Medical School and became one of the first practitioners to record meditation-related health improvements in patients with intractable pain. His stress-reduction techniques are now used in hospitals, clinics and by HMOs.

"In the last 25 years there's been a tidal shift in the field, and now there are 300 scientific papers on mindfulness," said Emiliana Simon-Thomas, science director for the Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley.

People who meditate show more left-brain hemisphere dominance, according to meditation studies done at the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

"Essentially when you spend a lot of time meditating, the brain shows a pattern of feeling safe in the world and more comfortable in approaching people and situations, and less vigilant and afraid, which is more associated with the right hemisphere," she said.Effect on aging

The most comprehensive scientific study of meditation, the Shamantha Project led by scientists at UC Davis, indicates meditation leads to improved perception and may even have some effect on cellular aging.Volunteers who spent an average of 500 hours in focused-attention meditation during a three-month retreat in 2007 were better than the control group at detecting slight differences in the length of lines flashed on a screen.When researchers compared blood samples between the two groups, they found the retreat population had 30 percent more telomerase - the enzyme in cells that repairs the shortening of chromosomes that occurs throughout life. This could have implications for the tiny protective caps on the ends of DNA known as telomeres, which have been linked to longevity."This does not mean that if you meditate, you're going to live longer," said Clifford Saron, a research neuroscientist leading the study at the UC Davis Center for Mind and Brain."It's an empirical question at this point, but it's remarkable that a sense of purpose in life, a belief that your goals and values are coming more into alignment with your past and projected future is likely affecting something at the level of your molecular biology," Saron said.Knutson's monk study at Stanford is in its early stages. He has some data collected from Stanford undergrads to use as part of the control group, but he still needs more novice meditators and monks to go into the MRI machine. It's an expensive proposition. Subjects are in the machine for eight to 12 hours a day, for three days, at $500 an hour.Dalai Lama donation

Knutson's study is funded by Stanford's Center for Compassion and Altruism Research and Education, which was started with a sizable donation of seed money from the Dalai Lama after his 2005 campus visit to discuss fostering scientific study of human emotion.Knutson and his team asked the monks and nuns to lie down in the MRI scanner and look at a series of human faces projected above their eyes. He asked them to withhold emotion and look at some of the faces neutrally, and for others, to look and show compassion by feeling their suffering.Next he flashed a series of abstract paintings and asked his subjects to rate how much they liked the art. What the monks and nuns didn't know was that Knutson was also flashing subliminal photos of the same faces before the pictures of the art."Reliably they like the art more if the faces they showed compassion to came before it," Knutson said, "Which leads to a hypothesis that there is some sort of compassion carryover happening."Extending compassion

Next Knutson asked the Buddhists to practice a style of meditation called "tonglen," in which the person extends compassion outward from their inner circle, first to their parent, then to a good friend, then to a stranger and last to all sentient beings. He wants to see whether brain activity changes depending on different types of compassion."There's a concern that scientists might be 'trying to prove meditation,' but we are scientists trying to understand the brain," said Matthew Sacchet, a neuroscience doctoral student at Stanford working with Knutson."The research has important possibilities for medicine, and also it could get rid of some of the fuzz and help make meditation more empirically grounded," he said. "If there is some kind of underlying structure to be understood scientifically, it could make things more clear for everyone."Meredith May is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. E-mail: mmay@sfchronicle.com

No comments:

Post a Comment