While some people have questioned the hierarchy in part, few have advocated for a complete reassessment - until now.

A team of evolutionary psychologists led by Douglas Kenrick of Arizona State University published an article, in the new issue of Perspectives on Psychological Science, proposing a revised pyramid, one informed by recent research defining our deep biological drives.

Here is some of the report on this article from Miller-McCune.

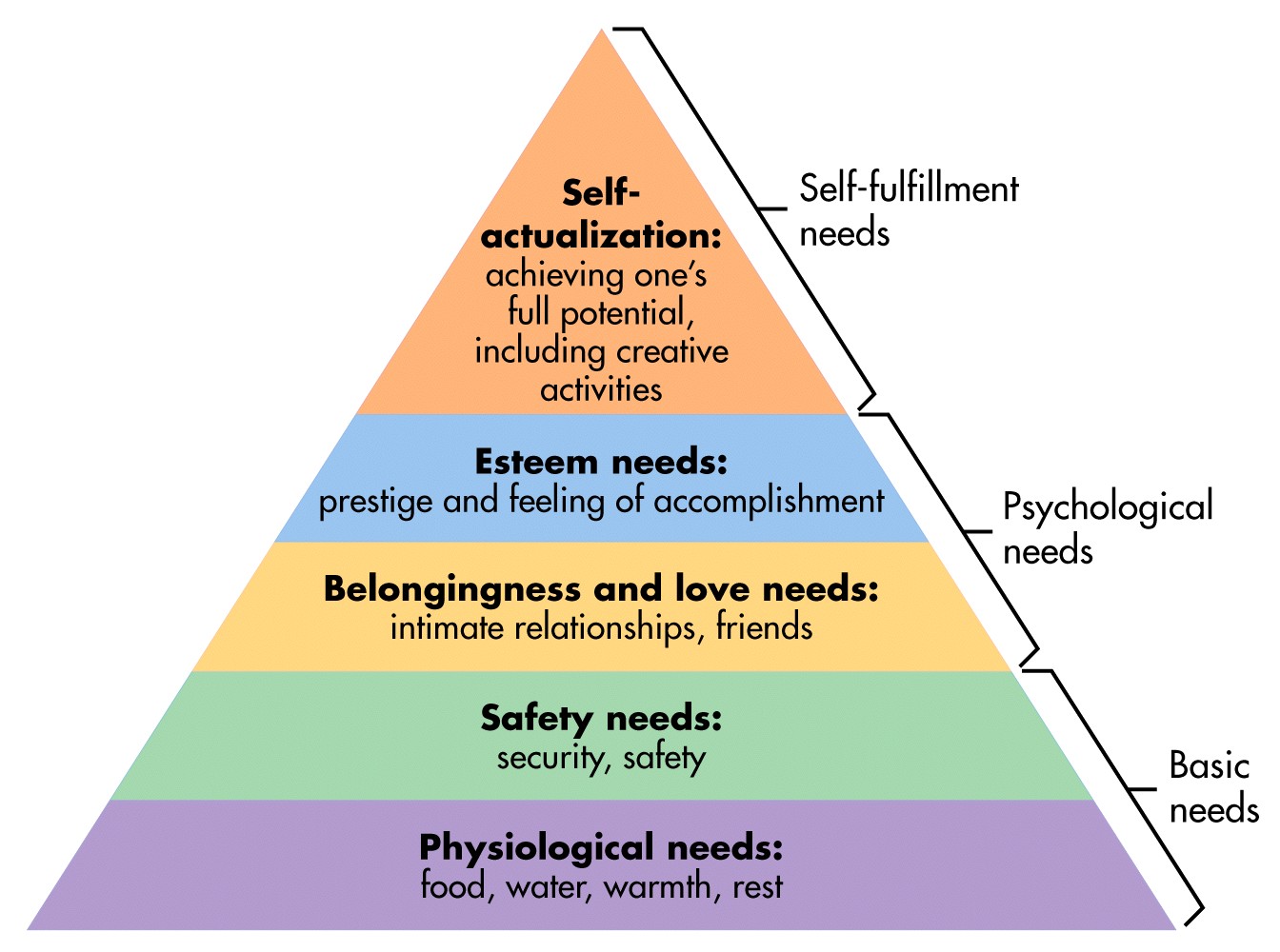

Maslow's model is based on the idea that we need to satisfy survival needs first and foremost - if we are worried about our basic food, shelter, and safety then there is not much hope of working on or even being aware of higher order needs.Maslow’s Pyramid Gets a Makeover

What are the fundamental forces that drive human behavior? A group of evolutionary thinkers offer an answer by revising one of psychology’s most familiar images.

By Tom JacobsAbraham Maslow’s Pyramid of Needs is one of the iconic images of psychology. The simple diagram, first introduced in the 1940s, spells out the underlying motivations that drive our day-to-day behavior and points the way to a more meaningful life. It is elegant, approachable and uplifting.

But is it also out of date?

That’s the argument of a team of evolutionary psychologists led by Douglas Kenrick of Arizona State University. In the latest issue of the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science, they propose a revised pyramid, one informed by recent research defining our deep biological drives.

Their new formulation is intellectually stimulating, but emotionally deflating. “Self-actualization,” the noble-sounding top layer of Maslow’s hierarchy, in their model has not only been dethroned, it has been relegated to footnote status. It has been replaced at the top with a more mundane motivation Maslow didn’t even mention: “Parenting.”

The new pyramid is based on the premise that our strongest and most fundamental impulse, which shapes our day-to-day desires on an unconscious level, is to survive long enough to pass our genes to the next generation. According to this school of thought, backed by considerable — though not irrefutable — evidence, all our achievements are linked in one way or another to the urge to reproduce.

In other words, aside from our powerful brains, we’re pretty much like every other living creature.

Given that we humans like to think of ourselves as special, this new pyramid will surely encounter strong resistance. But it could also become a shorthand way to clarify the often-misunderstood concepts of evolutionary psychology, which, its advocates insist, are not as meaning-denying and ego-deflating as we might think.

“There is such a thing as self-actualization, developing your inner potential, a self-need to become brilliant at whatever you’re doing,” says Kenrick, who studied classical guitar before devoting his professional life to academic research. “I just don’t think it’s divorced from biology.

“The reason our brains work this way — the reason we’re always so curious, we’re trying to solve problems, we’re trying to perfect the product of our creativity — it’s because when our ancestors used their big cerebral cortexes in those ways, the result was an increase in reproductive success.”

That’s on average, of course; individual results may vary. J.S. Bach fathered 20 children. Beethoven had none.

Once those lower level or basic needs are satisfied, we then can seek out a partnership so satisfy our bonding and relational needs, as well as our more individual needs for self-esteem and self-achievement. These are often family needs, as well as relational needs.

From there (although not everyone feels the need for interpersonal connections as strongly as others, and they may skip directly to a devotional life or an academic life) people then seek self-actualization, becoming the best, healthiest, most whole person possible. We may devote ourselves to art, to teaching, to spiritual practice, and so on, depending on what we find most valuable in life.

Despite the popularity of Maslow's model, Kenrick and his colleagues — Vladas Griskevicius, Steven Neuberg and Mark Schaller — felt the model needed to be updated with the recent findings from evolutionary psychology in mind.

What they have done, in essence, is throw out the top two tiers of Maslow's model and focus all their attention on expanding the bottom three stages into their seven stages (all of which are based on survival and reproduction - none of which are focused on self-actualization in any form) with a nod toward esteem as an issue (in terms of status).This notion of human beings aspiring to ever-higher levels of meaning has had lasting appeal. University of Michigan psychologist Christopher Peterson found more than 766,000 images of Maslow’s pyramid on the Internet. MIT psychologist Joshua Ackerman suspects its allure is based on several factors.

“One is that it fits people’s notions of the kinds of the goals that are important to them,” he says. “Second, it gives people a track on which to proceed through life. People everywhere tend to search for meaning in life. This gives people a structure by which to do that.”

Despite the pyramid’s continuing popularity, Kenrick and his colleagues — Vladas Griskevicius, Steven Neuberg and Mark Schaller — note some modern researchers consider it “quaint” and largely irrelevant. But during the years they spent studying deep-seated human motivations from an evolutionary perspective, Kenrick and his colleagues realized many of their findings lined up quite nicely with Maslow’s concepts. The lower rungs of his hierarchy — immediate physiological needs, safety and, a bit higher up, esteem — appeared quite solid in light of this new evidence.

But they also found several problems with the pyramid. We now know that needs, once they are met, don’t simply disappear; rather, they reappear when prompted by certain environmental cues. Watching a news report about a crime spree will trigger fears for our own safety, which can influence our opinions and behaviors even if that need is being effectively met. (More fancifully, Kenrick notes that many well-fed people love to watch cooking shows. Having a full belly doesn’t negate our fascination with food.)

So Kenrick and his colleagues created a new pyramid in which the needs overlap, rather than completely replace, one another.

“When a new one comes in, it doesn’t just cover up the old one the way a new city is built on ancient ruins,” he says. “The old and new continue to coexist.”

While few will take issue with that refinement, the other major change Kenrick and his colleagues propose is more problematic. They note that, from an evolutionary perspective, the idea that “self-actualization” would be at the top of the pyramid makes no sense. For our genes to survive and live on in the next generation, we don’t have to meet or exceed our potential: We just need to survive, attract a mate and have a child. From a genetic perspective, that’s plenty good enough.

So Kenrick and his colleagues revised the hierarchy to reflect this selfish-gene hypothesis. While their bottom four levels are highly compatible with Maslow’s — immediate psychological needs, self-protection, affiliation, status/esteem — their top three differ enormously. They are mate acquisition, mate retention and parenting.

“I think the biggest mistake Maslow made was he considered sexual gratification to be down there with the physiological needs, like hunger and thirst,” Kenrick says. “But we feed ourselves to survive; we have sexual relations for another reason. [The sex drive] has an intrinsic connection to what evolutionary theorists believe makes life go around, which is replication of genes. He kind of missed the boat on that.”

From my perspective, what they have done is eliminate psychological needs and made the pyramid all biological and social - to the point that in their model status is necessary before mate acquisition. Even that term, "mate acquisition," reduces a romantic partner to an object of reproduction.

Yes, human beings are part of the animal kingdom, but we have evolved to experience complex emotions and experiences including love, spirituality, and self-transcendence. To me, this proposed model, while it may hold some merit in what is covers, is too reductionist to be a true hierarchy of values.

The basic argument of evolutionary psychology is that all human behaviors are simply complex ways of acquiring a mate and reproducing. However, spiritual experiences such as self-transcendence and nonduality confer no discernible reproductive advantage and may even be a hindrance.

One other issue is development - for survival stages of development (essentially the first four of Wilber's stages or Spiral Dynamics stages) reproduction and survival are the prime concerns - but this becomes less and less true as people increase their developmental stages.

Journal Reference:

Kenrick, D.T., Griskevicius, V., Neuberg, S.L. & Schaller, M. (2010). Renovating the Pyramid of Needs: Contemporary Extensions Built Upon Ancient Foundations. Perspectives on Psychological Science; Vol. 5 No. 3: 292-314. doi: 10.1177/1745691610369469

From above: "They note that, from an evolutionary perspective, the idea that “self-actualization” would be at the top of the pyramid makes no sense. For our genes to survive and live on in the next generation, we don’t have to meet or exceed our potential: We just need to survive, attract a mate and have a child. From a genetic perspective, that’s plenty good enough."

ReplyDeleteI completely agree with you Bill, they seem to reduce everything to a biosocial level with no regard for more subtle complexities of causality and motivation.

We have lived in a post-survival selection context for thousands of years! Very few people find it difficult to find mates - therefore the most basic selective pressures have been somewhat diminished. Some of our species now live in contexts where they must develop meaning systems, and therefore behavior repertoires, primarily through symbolic, egoic and cultural means means. This is, moreover, exactly why Spiral Dynamics emphasizes the role of "life conditions" in value/meaning activation.

Perhaps such "evolutionary psychologists" (which, with these folk at least, is really just a revised sociobiology) would also do well to remember that we have a frontal cortex, and the capacities that become activated therein do so within a complex semiotic network. The subsequent coping and requisite wayfinding can generate very non-biologically oriented intentionalities, that often augment, extend and redirect our more basic genetic and physiological drives.

We are utterly entangled beasts...

m-

Maslow often talked about the "biological rootings of the value life" and you might enjoy the audio recording I've posted in re the biology of the hierarchy of human values.

ReplyDeleteOf course, he also saw homeostasis through the formula of the torsion pendulum rather than the gravity pendulum. Important when working with dichotomy transcendence because of the reversed moments of inertia.

See also Carl Hempel's stuff on biology vis-a-vis the "covering law" which proposes 2 Weltanschauungen: statistical versus observational. Then look at Maslow's two (and only two) types in his "Theory Z" paper. See the tracks?