With all the attention being focused on China as they host the Olympics, it seems there just isn't enough attention being focused on how repressive the Chinese government is, especially in the ethnically diverse regions such as Tibet.

This article from Weekend America looks at the struggle of one Tibetan exile to return to his native land in order to save as much of the culture as possible (his focus was folk songs) before the now Chinese dominated region loses its rich ethnic heritage forever.

He was sentenced to 18 years in prison for espionage, but only served 6+ years when China released some political prisoners prior to a visit by George Bush.

The Crime of Cultural Preservation

Lu Olkowski

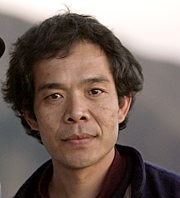

AUGUST 9, 2008Ngawang Choephel always dreamed of living in the country where he was born. But in 1968, his mother fled with him to a refugee camp in Southern India from Chinese rule in Tibet. He was only two years old.

The experience left his mother too afraid to ever return to Tibet, and Choephel longing for a home he never knew. He constantly asked himself, "What is it like to have your own country?

"When you grow up as a stateless person, you never experience that. And that was back in my head all the time when I was growing up," Choephel says.

He often had these thoughts late at night, when he was tucked into bed, listening to the adults singing and dancing. "I really heard a lot songs from elder Tibetans. That's what they brought with them. They brought objects and things from Tibet, but there's no life I can see. The music was that kind of life, I can feel it."

As a teenager, Choephel fell in love with Bollywood movies and music; they made Tibetan culture seem kind of old-fashioned. He was torn. He wasn't Indian, but he didn't feel completely Tibetan either.

After high school, he started performing and teaching Tibetan music to teenagers in the refugee camp. He didn't think they would identify with folksongs---after all he didn't when he was a teenager---so he worked with them to write original songs about their lives in exile.

In 1993, Choephel was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study musicology and filmmaking at Vermont's Middlebury College. He got there and discovered an incredible library of music from around the world. There was a huge amount of material about Chinese music, "and, there was a little section of Tibet. It was less than 3 minutes." This inspired Choephel to go to Tibet and record Tibetan folk music. "I have to do this. I really told myself, I have to do this," Choephel says.

There's a reason not much Tibetan music has been preserved. At that time, the Chinese government didn't necessarily see a distinction between Tibetan culture and politics---so even something as innocent as filming folksongs could be considered a punishable act of resistance.Despite the risks involved, Choephel decided to go. He wanted to immerse himself in the music and to see where he was born; he was hoping to find something that would make him feel more Tibetan.

When Choephel first got to the Tibetan capital of Lhasa, the prospect of collecting Tibetan music seemed bleak. "I was really shocked because the first sound I heard was Chinese music--coming from everywhere--from the stores, loudspeakers," he recalls. "The sound is totally Chinese. And then finally, when I went into the countryside, I found what I was looking for. I was really inspired that they still can sing despite all that they went through. When I saw them smile, it was really inspiring."

Choephel says folksongs are the purest form of Tibetan expression because they originated directly from the lives of ordinary Tibetans. "There are songs about every activity you do in daily life: while you work to build the house, songs for weddings, songs to sing while drinking, songs to sing while you are milking, songs to sing while you are churning the butter. There songs for everything."He spent two months driving through the countryside filming people singing. He says he was lost, in a wonderful way.

That wonderful feeling was short lived. As he headed towards his birthplace, he was stopped and arrested by China's State Security Bureau, which is the equivalent of the CIA in the United States. When they told Choepel's driver to leave, "I saw the truck vanish leaving me with these nine police, I thought I will never be able to go back there."

Choephel was sentenced to eighteen years for espionage, a sentence served in four different prisons he says were more or less the same: a concrete cell with a bed and a bucket for a urinal. In the morning, he got hot water to drink with a small piece of steamed bread or cooked lettuce, a far cry from his life as an academic in Middlebury, Vermont.

Choephel was held with other political prisoners, men who risked their lives as part of the Free Tibet movement. He didn't feel like he belonged; he couldn't shake the fact that unlike them, he grew up in exile. "They're so comfortable with who they are," he explains "Prison is not a place where you want to go, but it is a place where you have time to think. It is not a place where you want to die, but it is a place where you can transform yourself."

Prison put Choephel's Tibetan values to the test. Through prayer, he learned how to remain mentally strong, even as his body grew weaker. Seeing how the other prisoners maintained their dignity and serenity taught him a lot about what it meant to be Tibetan. "I'm very very comfortable now as a Tibetan than I was before," he says.

To pass the time, he learned folksongs from other prisoners, writing lyrics into a notebook he made out of cigarette wrappers until the guards caught him. After that he memorized their songs. He wrote a song with one prisoner who became a good friend. Their song is named Yarlung Tsangpo, after Tibet's largest river. "Yarlung Tsangpo is singing a sad song," read the lyrics, "And the land of snow is overcast and suffering. Because of my past negative karma, I may have to go through this. Oh, Lord, but there may be an end to this."

Choephel was released in 2002 after six and a half years in prison. His health was in shambles, but when he got out, he thanked the Chinese government in a written statement. Choephel says the Chinese government used him to improve diplomatic relations with the West. The world's eyes were on China then, President Bush was preparing to meet with Chinese President Jiang Zemin and the UN was examining China's human rights record. Choephel was a valuable card played at a crucial moment.

International scrutiny is once again on China. Protests have plagued the build-up to, and excitment surrounding the Beijing Olympics and this time, it's Choephel's turn to play a valuable card at a crucial moment. He has chosen to speak publicly about his experiences after all these years because he thinks there is an opportunity, "not for Tibet, not for China, but for the entire world to solve the issue of Tibet through non-violence. With what's happening in the world right now, the growing anger all over the world, I think that we can give our world an example."

Even after his imprisonment, Choephel refuses to be bitter or confrontational. He repeatedly insists that what happened to him is not a tragedy but a success, because he was ultimately able to find what he was looking for: folksongs and his Tibetan identity. The real tragedy, according to him, is that the issue of Tibet has yet to be solved.

No comments:

Post a Comment