So what determines a "serious offense"?

I can see this ruling being misused in a multitude of ways, not least of which is arresting suspects as a "fishing expedition" to charge them with previous crimes or suspected crimes.

Once the DNA is collected, where does it go, who takes possession of it? Does it get entered into the national database? Does it get destroyed if the person is innocent? There a lot of issues with this ruling, and this article from Pacific Standard looks at the slippery slope this ruling entails.

DNA Collection Is the New Fingerprinting

What will it mean for crime suspects—and for victims?

June 3, 2013 • By Lauren Kirchner

(ILLUSTRATION: JEZPER/SHUTTERSTOCK)

On Monday, the Supreme Court gave the OK to the controversial practice of cops collecting DNA samples from crime suspects under arrest. In a 5-4 ruling, the justices decided that swabbing a person’s cheek prior to their conviction of any crime did not constitute an unreasonable search—so long as the suspect was under arrest “for a serious offense” and had been brought “to the station to be detained in custody.”

According to NBC News, 28 states and the federal government already adhere to this practice. This case dates back to the 2009 arrest of 26-year-old Alonzo King on assault charges. Maryland police swabbed his cheek after his arrest, and by running it through a DNA database, matched him to an unsolved rape case.

The slippery-slope argument here is a fitting one, of course. If cops can collect DNA without a conviction, without a warrant, then how soon will it be until they can collect it from anyone during routine traffic stops, or any time? Or until other institutions besides law enforcement can? Justice Scalia, writing in his dissent on Monday, addressed those concerns.

“Today’s judgment will, to be sure, have the beneficial effect of solving more crimes,” he wrote. “Then again, so would the taking of DNA samples from anyone who flies on an airplane.”

Justices voting in the majority compared DNA collection to a more advanced version of fingerprinting. In his oral argument back in February, Judge Alito stressed the significance of this new technology, which has the potential to solve countless murders and rapes with “a very minimal intrusion on personal privacy.”

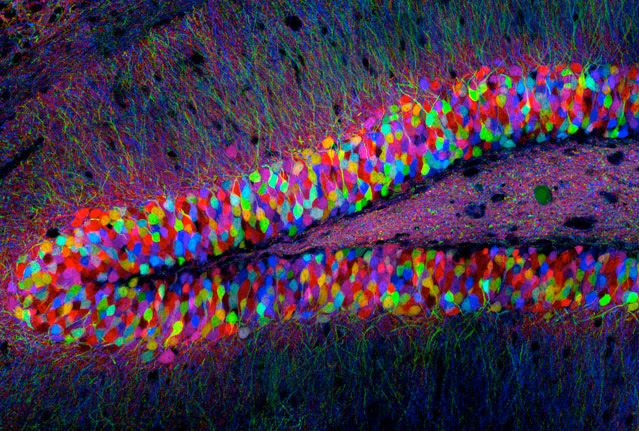

Is the DNA-fingerprint comparison an accurate one? In an age when an artist can pick up an old piece of chewing gum from the sidewalk and create a 3-D model of the gum-chewer’s face, it sounds a bit naïve.

Monday’s Supreme Court ruling is only one of many difficult cases that will arise, here and elsewhere, surrounding DNA sampling and sequencing technology. High-publicity instances of new DNA evidence freeing a wrongly-convicted prisoner may increase public support for DNA collection by law enforcement. At the same time, DNA-sequencing companies like 23AndMe and EasyDNA entering the mainstream may also make people feel more comfortable with the idea that something as private and complex as their genetic makeup can be mined for benefits both personal and societal. Canadian law enforcement officials are lobbying their government on the same issue now. In the U.K., a police commissioner is defending the right of cops to take samples from children under the age of 18 who are suspected of even minor offenses.

But what about non-criminal DNA databases? Privacy protection concerns should apply to victims of crime just as much, if not more, than they do to crime perpetrators and suspects. An article in Trends in Genetics out last month addressed the very tricky balance between identifying victims and protecting those victims’ privacy when DNA-collection is involved in the process.

According to the report’s authors, Joyce Kim and Sara H. Katsanis of Duke University, government agencies are increasingly using DNA databases specifically to identify victims of human trafficking and other human-rights violations. For instance, they write, “Routine, systematic databasing of family member profiles of missing persons” may help identify kidnapping or murder victims. Databases could also prevent children from being placed up for illegal adoptions. If there is ever a proper use for DNA in law enforcement, the authors argue, this is it—but there must be boundaries set, and soon.

“Scholars estimate that, globally, government-operated DNA databases will grow from approximately 30 million profiles in 2011 to 100 million profiles in 2015,” according to the report. Many of the existing collection programs, Katsanis and Kim note, “involve vulnerable populations, including children, sex workers, and persons whose legal or resident status may be questioned.”

The coordination and ownership of these databases is also at issue. “Government-held DNA databases can be readily monitored for quality and security, but less-secure private entities, such as NGOs or entities with diplomatic immunity, could minimize abuse of power,” the authors write. And the more centralized and internationally-accessible the databases get, the more security issues and legal complications will potentially arise.

Even outside of the law-enforcement and crime-prevention realms, the ownership of genetic information is an ongoing debate. California legislators are currently considering a new law to require genetic-testing firms like 23AndMe and EasyDNA to obtain a person’s permission before processing their information and putting it in their genetic database. Currently, it is perfectly legal to send someone else’s “genetic material” to one of these companies, for instance, for paternity information or, as one company puts it, “infidelity testing.” From the San Jose Mercury News: “‘We have privacy laws in place to protect health and financial information,’ said the bill’s author, Alex Padilla, D-Pacoima. ‘But arguably the most personal information about us—our own genetic profile—isn’t protected.’”

What’s more, a recent MIT study showed how easy it is for genetic databases to be hacked, making genome theft an actual, and frightening, possibility. “By means of your DNA, nature provides you with a security flaw that makes Microsoft Windows look like Fort Knox,” writes Michael White elsewhere on Pacific Standard today.

Having a not-quite-accurate 3-D model made of your face is one thing; putting detailed medical information in the hands of hackable Internet sites is quite another. Clearly, the security of these DNA databases should be just as pressing an issue as the collection of people’s DNA in the first place, criminals or no.