This is the second part of a multi-part post (originally intended to be two parts) on Bernard Baars' Global Workspace Theory and the future evolution of consciousness (Part One is here). In Part One, I outlined the basic ideas of GWT, suggesting that it may be the cognitive model that is closest to being integral while still being able explain the actual brain circuitry involved in creating self-awareness, the sense of an individual identity, the development of consciousness through stages, the ability of introspection to revise brain wiring, and the presence of multiple states of consciousness.

In this post, I want to establish more foundation for a paper that seeks to explain how our consciousness will evolve in the future - The Future Evolution of Consciousness by John Stewart (ECCO Working paper, 2006-10, version 1: November 24, 2006). His work assumes some specialized knowledge of cognitive developmental theory, so this post will attempt to provide a little more solid foundation for the ideas that will come up in the next posts.

In order to really grasp the model Stewart offers, it might help to revisit one of the ideas of Global Workspace Theory, particularly how the process of being conscious allows us to direct the "spotlight" in the theater of mind.

The Conscious Access Hypothesis

This was an idea that was mentioned in the first post - "consciousness facilitates widespread access between otherwise independent brain functions" (Baars, 2002, The Conscious Access Hypothesis: Origins and Recent Evidence, Trends in Cognitive Science, 6:2).

Let's start with this idea - to me it is central to the rest of the argument.

One of the foundations for GWT is the existence of working memory (WM), which is generally defined as rehearsable immediate memory, and it includes inner speech and visual memory. Baddeley (1992), one of the first researchers to define working memory as an aspect on the modular brain model in 1974 (although Karl Pribram was one of the group that coined the term in the 1960s), defined working memory in this way:

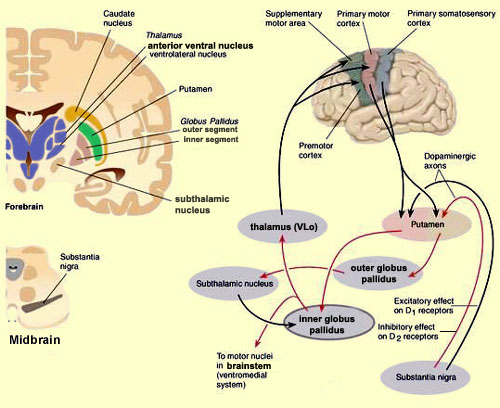

Working memory has been found to require the simultaneous storage and processing of information. It can be divided into the following three subcomponents: (i) the central executive, which is assumed to be an attentional-controlling system, is important in skills such as chess playing and is particularly susceptible to the effects of Alzheimer's disease; and two slave systems, namely (ii) the visuospatial sketch pad, which manipulates visual images and (iii) the phonological loop, which stores and rehearses speech-based information and is necessary for the acquisition of both native and second-language vocabulary. (Baddeley, 1992, Working Memory; Science, 255:5044)Neuroscience research (often based on patients with brain lesions) finds that there are several brain regions involved in working memory, including the frontal cortex, parietal cortex, anterior cingulate, and parts of the basal ganglia.

The conscious elements of WM (input, rehearsal, and recall are all available to awareness and can be reported as conscious events, meeting the criteria for operational consciousness), are widely distributed throughout a variety of neural networks, which is consistent with Baars conscious access hypothesis (CHA).

Importantly, however, working memory can only hold about seven discreet objects at a time, and this falls to four if there is not time for rehearsal.

The seven plus or minus two limit applies to visual objects, words, numbers, colours, musical notes, and any other set of unrelated elements. It drops even below seven when we cannot rehearse the items, down to about four. In a brain of 100 billion neurons, this upper limit on working memory is fantastically small. A cheap calculator can store more numbers than a human being, in immediate memory. Why, over two billion years of biological evolution, has the brain not evolved a bigger capacity to hold numbers? (Baars, 1997, In the Theatre of Consciousness: Global Workspace Theory,A Rigorous Scientific Theory of Consciousness; Journal of Consciousness Studies, 4)The mind seems ill-designed to remember anything more than a local phone number. Even more interesting is that we can only focus on one dense input stream of information at a time. Studies on multitasking have confirmed that when we multitask we are not doing any of the tasks well. For most people, conscious involvement with one stream of information will disrupt any other stream on which the person was focused. Working memory imposes strict limitations on the contents of consciousness.

Complex behaviors that have become routine acts, however, do not encounter this limitation - they are performed outside the conscious workspace, where the brain is massively parallel and speedy in its processing capabilities, and where multiple objects/skills/actions can be processed simultaneously. In fact, much of our sensory processing - which likely dominated consciousness when we were infants, is handled by these unconscious systems, unless we direct our awareness to those sensory channels.

This aspect of the brain allows that when we become proficient at a complex skill through assembly, rehearsal, and learning (the creation of neural circuitry encoded for this skill or behavior), that initially took all of our concentration, we now can perform it accurately and quickly with minimal conscious attention (Bargh and Chartrand, 1997, The unbearable automaticity of being; American Psychologist, 54:7).

There have been many books of late that cover this topic in detail, including Daniel Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow, Leonard Mlodinow's, Subliminal: How Your Unconscious Mind Rules Your Behavior, David Eagleman's Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain, and Michael Gazzaniga's Who's in Charge?: Free Will and the Science of the Brain.

This "procedural" knowledge (Kahneman's Type 1 thinking) is what allows us to drive to the grocery store or to work while thinking about some personal issue or getting caught up in a radio show discussion and then not remember any of the drive we just completed. It is a learned skill that takes little or no conscious attention. But if road traffic is terrible or there is an accident and we have to find another route, then we must deal with the drive in our workspace, which leaves us unable to get so deeply involved in the radio show.

The flip-side of this, however, is that we can create access to any part of the brain using consciousness (as the chart above shows). And this unique ability (a recent evolutionary adaptation?) is what provides us with the ability to influence - and increase - our level of cognitive development, our level of consciousness, an idea that was considered impossible (outside of some spiritual traditions) until the last decade or two.

To gain control over alpha waves in the cortex we merely sound a tone or turn on a light when alpha is detected in the EEG, and shortly the subject will be able to increase the amount of alpha at will. To control a single spinal motor neuron we merely pick up its electrical activity and play it back over headphones; in a half-hour subjects have been able to play drumrolls on their single motor neurons! (Baars, 1997)The control of brain waves is an interesting and seemingly mind-boggling skill, and it has been a part of many studies on the ability of advanced meditators to control brain waves (see Lutz, Greischar, Rawlings, Ricard, and Davidson, 2004). As additional proof of this phenomenon, here is Ken Wilber, a very experienced meditation practitioner, stopping his brain waves:

This idea of conscious access to what are generally considered inaccessible parts of the brain is an important element of GWT, and it is crucial to the idea of evolving consciousness that we will examine in future posts.

In Stewart's paper, he provides his own version how the conscious access hypothesis works in GWT as it relates to holding something in consciousness:

It is evident that being conscious of an event goes hand in hand with the availability of the event to other resources—if we are conscious of something, we are able to give it attention, think about it, introspect in relation to it, talk about it, feel in relation to it, mull over it, and act on it. When we are conscious of something, the experience is available for other resources to operate on. If we are not conscious of something, the experience is not available to other resources.When we meditate on an image or a koan, try to solve a problem, or work out a personal decision in our heads - all of these processes require us to hold objects of awareness in the workspace that is working memory. Baars had relied initially on experimental evidence that suggested an image held in conscious awareness triggers access to a variety of other neural circuits, but it was not until his work with Gerald Edelman - and Edelman's Dynamic Core model - that there was empirical evidence.

The concept of a Dynamic Core provides a mechanism for Global Workspace events by reentrantly projecting neural signals throughout the cortex. The distributed neural activity that underlies conscious contents simultaneously projects one-way neural signals throughout the cortex. Such directed propagation of activity among widely dispersed large populations of cortical neurons is reflected in event-related potentials.

Long-distance propagation of functional brain signals has been known for many years in the context of such potentials (Steriade, 2006). These observations suggest that the concept of a Global Workspace is compatible with the notion that a brief pattern of activity in the Dynamic Core with a specific content, e.g., a particular mental image, momentarily activates numerous cortical areas. (Edelman, Gally, and Baars, 2011, Biology of consciousness; Frontiers in Consciousness Research, 2:4)And just to clarify, here is an article by Edelman and Tononi, (1998, Consciousness and Complexity; Science, 282:1846), that lays out their model of the Dynamic Core:

We suggest the following:

1) A group of neurons can contribute directly to conscious experience only if it is part of a distributed functional cluster that achieves high integration in hundreds of milliseconds.

2) To sustain conscious experience, it is essential that this functional cluster be highly differentiated, as indicated by high values of complexity.

We propose that a large cluster of neuronal groups that together constitute, on a time scale of hundreds of milliseconds, a unified neural process of high complexity be termed the “dynamic core,” in order to emphasize both its integration and its constantly changing activity patterns. The dynamic core is a functional cluster: its participating neuronal groups are much more strongly interactive among themselves than with the rest of the brain. The dynamic core must also have high complexity: its global activity patterns must be selected within less than a second out of a very large repertoire.In essence, this model - or the integration of these two models - explains how the objects of consciousness gain access to and associate with memories, images, thoughts, perceptions, and sensations that otherwise were not directly available to consciousness (more on a related topic will come up later in this discussion).

With that foundation, we can now turn to the early parts of John Stewart's paper.

The Future Evolution of Consciousness

Here is the abstract:

What potential exists for improvements in the functioning of consciousness? The paper addresses this issue using global workspace theory. According to this model, the prime function of consciousness is to develop novel adaptive responses. Consciousness does this by putting together new combinations of knowledge, skills and other disparate resources that are recruited from throughout the brain. The paper’s search for potential improvements in the functioning of consciousness draws on studies of the shift during human development from the use of implicit knowledge to the use of explicit (declarative) knowledge. These studies show that the ability of consciousness to adapt a particular domain improves significantly as the transition to the use of declarative knowledge occurs in that domain. However, this potential for consciousness to enhance adaptability has not yet been realised to any extent in relation to consciousness itself. The paper assesses the potential for adaptability to be improved by the conscious adaptation of key processes that constitute consciousness. A number of sources (including the practices of religious and contemplative traditions) are drawn on to investigate how this potential might be realised.These are the essential points:

- A shift during human development from using implicit knowledge to using explicit, declarative knowledge - The Declarative Transition - is essential to higher order cognition

- When consciousness adapts to a particular domain, it improves significantly as the transition to the use of declarative knowledge occurs in that domain

- The ability of consciousness to enhance adaptability remains to be fully realized in relation to consciousness itself (NOTE: I disagree, see below, on advanced meditators)

- Adaptability potentially can be improved by consciously adapting key processes that constitute consciousness (self-awareness, introspection, and mindfulness)

Consciousness operates in the main at the growing tip of behaviour where new responses are created.***To what extent could the way in which consciousness operates be changed to enhance the adaptability of humans? Could the significant contribution made by conscious processes to our adaptability be improved further by modifying the way consciousness functions?

Ken Wilber always used to speak about integral being the "frothy edge" of consciousness evolution, and it seems he had the right idea (although Stewart is a reader of Wilber, so he may be channeling Wilber's language about the "growing tip," another Wilber term).

Let's begin with The Declarative Transition as the first step in answering these questions.

There are two basic forms of knowledge, procedural knowledge and declarative knowledge. Procedural knowledge is generally implicit skill knowledge (often embodied), for example how to ride a bicycle, how to construct a sentence, or how to break the ice at a cocktail party - these are embodied skills, the details of which are not readily accessible to consciousness, nor are they easily explained verbally. Acquiring this knowledge generally takes multiple trials, although single-trial learning is not unknown. This knowledge is often skill-specific - it does not adapt well to use in other purposes (knowing how to ride a bike offers little useful carry-over to learning how to hit a baseball). (Ten Berge and Van Hezewijk, 1999; Procedural and Declarative Knowledge: An Evolutionary Perspective; Theory & Psychology, Vol. 9:5).

Declarative knowledge, however, is explicit, not skill-specific, and readily available to verbal consciousness. Broadbent (1989, Lasting representations and temporary processes; in Varieties of memory and consciousness: Essays in honor of Endel Tulving) identifies declarative knowledge as symbolic knowledge, while Tulving (1985, How many memory systems are there? American Psychologist, 40:4) divides declarative knowledge into semantic and episodic, although he really defines episodic knowledge (or memory) as a sub-type of semantic knowledge (or memory), which is then a sub-type of procedural knowledge (or memory). For the purposes of working with knowledge more specifically, Ten Berge and Van Hezewijk combine semantic and episodic in the form of declarative knowledge.

One important ability declarative knowledge allows is that we can store associations, store information as either true or false, verbalize any of this at will, and perform "operations" on any piece of knowledge we possess. This is the form of knowledge we associate with thinking, deliberating, and theorizing.

Interestingly, declarative knowledge can be changed or altered as we acquire new knowledge, which may be one possible definition of learning - as well as being altered each time it is brought into the workspace. (This is also the reason first-person, eye-witness testimony is notoriously unreliable.) Additionally, declarative knowledge is not available to consciousness unless it is recalled through questions or other forms of targeted recall. Moreover, we can't explain how we recall the information, the process of recall is not available to consciousness.

Annette Karmiloff-Smith (1992, Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science) developed some of the original theoretical work in this field, seeking to explain how children acquire knowledge and then learn to manipulate it - a model she named representational redescription (RR). Her model falls somewhere in between Jean Piaget's constructivism and Jerry Fodor's nativism, including elements from both.

It involves a cyclical process by which information already present in the organism's independently functioning, special-purpose representations, is made progressively available, via redescriptive processes, to other parts of the cognitive system. In other words, representational redescription is a process by which implicit information in the mind subsequently becomes explicit knowledge to the mind, first within a domain and then sometimes across domains.She describes her RR model as a phase model and not a stage model:

[T]he RR model is a phase model, as opposed to a stage model. Stage models such as Piaget's are age-related and involve fundamental changes across the entire cognitive system. Representational redescription, by contrast, is hypothesized to occur recurrently within microdomains throughout development, as well as in adulthood for some kinds of new learning.She presents two distinct phase series by which information is encountered and internalized as part of the learning process. The first model looks at the three phases of development within a microdomain.

1. Representational adjunctions - A data driven focus on information from the external environment. Once stabilized, the new representations are added to the existing collection without any linkage or interaction. This stage is complete when the new representation reaches the level of "behavioral mastery," meaning that this specific representation is used correctly in practice.

2. Internal representations - The child's representations of knowledge within a given microdomain are given precedence over new incoming data. By focusing on the internal representations over external information, there can be new errors or inconsistencies. An example of this might be a very young child who learns that a large Great Dane is a dog, so when he sees a horse for the first time, the large four-legged animal must also be a dog. This is viewed by Karmiloff-Smith as a behavior mistake, not of the representational system.

3. Reconciliation - Internal representations and external data are reconciled, creating a balance between the needs for internal and external control: "In the case of language, for example, a new mapping is made between input and output representations in order to restore correct usage."

These three phases are reiterated with the acquisition of each new data representation. So, then, how are these internal representations formatted so that they can sustain this reiterative process? Karmiloff-Smith argues for a series of four (at least) hierarchical levels at which knowledge is represented and represented:

I have termed them Implicit (I), Explicit-1 (El), Explicit-2 (E2), and Explicit-3 (E3). These different forms of representation do not constitute age-related stages of developmental change. Rather, they are parts of a reiterative cycle that occurs again and again within different microdomains and throughout the developmental span.Level I representations take the form of procedures (remember that procedural knowledge is non-verbal) for making sense of and responding to data in the external world. She identifies a series of restrictions (constraints) that operate on the representational adjunctions that arise at this level:

- Information is encoded in procedural form.

- The procedure-like encodings are sequentially specified.

- New representations are independently stored.

- Level-I representations are bracketed, and hence no intra-domain or inter-domain representational links can yet be formed.

A procedure as a whole is available as data to other operators; however, its component parts are not. It takes developmental time and representational redescription (see discussion of level El below) for component parts to become accessible to potential intra-domain links, a process which ultimately leads (see discussion of levels E2 and E3) to inter-representational flexibility and creative problem-solving capacities. But at this first level, the potential representational links and the information embedded in procedures remain implicit.Following the acquisition of level I representations, in the form of implicit procedures, levels El, E2, and E3 comprise a "reiterative process of representational redescription."

Here are some brief descriptions of each phase of the encoding process:

According to Karmiloff-Smith, the original level-I representations are not impacted by the E1 phase - they remain intact in the brain and remain available for use in goals that require this type of implicit skill. The E1 representations are then available for use where more explicit knowledge is necessary. She is careful to stress, however, that although the E1 representations are available for cognitive processing, they are not available for conscious access or verbal representation.Level-El representations are the results of redescription, into a new compressed format, of the procedurally encoded representations at level I. The redescriptions are abstractions in a higher-level language, and unlike level-I representations they are not bracketed (that is, the component parts are open to potential intra-domain and inter-domain representational links).The El representations are reduced descriptions that lose many of the details of the procedurally encoded information. ... The redescribed representation is, on the one hand, simpler and less special purpose but, on the other, more cognitively flexible (because it is transportable to other goals). Unlike perceptual representations, conceptual redescriptions are productive; they make possible the invention of new terms.

[NOTE: This is probably much more detail than necessary for understanding the paper by Stewart, but it feels important to establish that there are very fine processes involved in knowledge acquisition, and that the shift from procedural knowledge to declarative knowledge is not completed in one swift move.]

On the E2 phase:

At level E2, it is hypothesized, representations are available to conscious access but not to verbal report (which is possible only at level E3). Although for some theorists consciousness is reduced to verbal reportability, the RR model claims that E2 representations are accessible to consciousness but that they are in a similar representational code as the El representations of which they are redescriptions. Thus, for example, El spatial representations are recoded into consciously accessible E2 spatial representations. We often draw diagrams of problems we cannot verbalize. The end result of these various redescriptions is the existence in the mind of multiple representations of similar knowledge at different levels of detail and explicitness.And last, the E3 phase, which is roughly equivalent to declarative knowledge:

At level E3, knowledge is recoded into a cross-system code. This common format is hypothesized to be close enough to natural language for easy translation into statable, communicable form. It is possible that some knowledge learned directly in linguistic form is immediately stored at level E3.23 Children learn a lot from verbal interaction with others. However, knowledge may be stored in linguistic code but not yet be linked to similar knowledge stored in other codes. Often linguistic knowledge (e.g., a mathematical principle governing subtraction) does not constrain nonlinguistic knowledge (e.g., an algorithm used for actually doing subtraction24) until both have been redescribed into a similar format so that inter-representational constraints can operate.And one final clarification from Karmiloff-Smith on her RR model:

Before I conclude my account of the RR model, it is important to draw a distinction between the process of representational redescription and the ways in which it might be realized in a model. The process involves recoding information that is stored in one representational format or code into a different one. Thus, a spatial representation might be recoded into linguistic format, or a proprioceptive representation into spatial format. Each redescription, or re-representation, is a more condensed or compressed version of the previous level. We have just seen that the RR model postulates at least four hierarchically organized levels at which the process of representational redescription occurs.For those interested in a cybernetic learning model based in cognitive neuroscience, this book by Karmiloff-Smith, Beyond Modularity: A Developmental Perspective on Cognitive Science, is still considered a classic, despite being published in 1992.

In Stewart's model, the Declarative Transition is the move from Level-I implicit/procedural knowledge through the E1, E2, and E3 phases which constitute the transformation of implicit procedural knowledge to explicit declarative knowledge. Once a skill or process reaches the stage of declarative knowledge, it is rarely called into consciousness unless it is targeted directly by some cue, such as a question or when someone else seeks an explanation.

We know, now, after years of studying these brain functions, that the more often a memory, skill, or piece of knowledge is recalled and rehearsed, the more strong wired it becomes in the brain. The old cliche is that "practice makes perfect" - but the reality is that practice makes permanent.

When a particular skill or procedure has been revised and expanded using declarative knowledge, it becomes automatic and unconscious again through a process of proceduralization. Stewart summarizes the high-level processing made possible by the proceduralization of declarative memory as unconscious schema:

In any particular domain in which a declarative transition unfolds, the serial process of declarative modelling progressively build a range of new resources and other expert processors, including cognitive skills. Once these processors have been built and proceduralized, they perform their specialist functions without loading consciousness—their outputs alone enter consciousness, without the declarative knowledge that went into their construction. The outputs are known intuitively (i.e. they are not experienced as the result of sequences of thought), and complex situations are understood at a glance (Reber 1989). As noted by Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1987), a person who achieves behavioural mastery in a particular field is able to solve difficult problems just by giving them attention—consciousness recruits the solutions directly from the relevant specialist processors.In the next installment, we will look at the process of "evolutionary declarative transitions," as well as additional neuroscience foundations for the evolution of consciousness.