The Wall Street Journal reviews Jerome Kagan's new book, Psychology's Ghosts: The Crisis in the Profession and the Way Back - a series of four meditations on big issues in psychology: Missing Contexts, Happiness Ascendant, Who Is Mentally Ill? and Helping the Mentally Ill.

I am probably most interested in the first chapter - it has been concern of mine for a long time (thanks to Wilber's integral model) that so much context is missing from how we think about mental illness and the people who suffer with it. (Even Wilber's own work misses some important context issues, relying too heavily on the idea of the singular Self and often examining it in isolation from other selves.)

This review is quite positive and supportive - I look forward to reading this new book.

Psychology and Its Discontents

We see an area in the brain 'light up' when we think about a topic, and assume we know something about thought. But what, exactly?

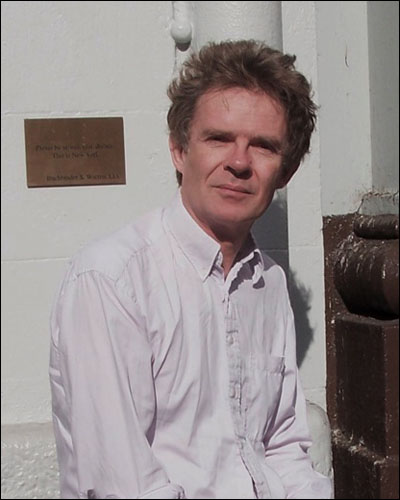

By CAROL TAVRIS

In his long and distinguished career, Jerome Kagan, now emeritus professor of psychology at Harvard, has written numerous books for general audiences on major discoveries and controversies in his field, particularly in his specialty of child development. In works such as "Three Seductive Ideas" (1998), he developed a style of discussing three or four different topics in a series of essays, interweaving each with data and observations across psychology, history and culture, and tying them together with an overarching theme. Or not.

Mr. Kagan's latest effort, "Psychology's Ghosts," might be called "Four Seductive Ideas," since it consists of his assessment of four problems in psychological theory and clinical practice. The first problem is laid out in the chapter "Missing Contexts": the fact that many researchers fail to consider that their measurements of brains, behavior and self-reported experience are profoundly influenced by their subjects' culture, class and experience, as well as by the situation in which the research is conducted. This is not a new concern, but it takes on a special urgency in this era of high-tech inspired biological reductionism.

If we can find which area of the brain lights up when we think about love or chocolate or politics, we assume we know something. But what, exactly, do we know? Sometimes less than we think. "An adolescent's feeling of shame because a parent is uneducated, unemployed, and alcoholic," Mr. Kagan writes, "cannot be translated into words or phrases that name only the properties of genes, proteins, neurons, neurotransmitters, hormones, receptors, and circuits without losing a substantial amount of meaning"—and meaning is as fundamental to psychology as genes are to biology. Many psychological concepts, he notes, including fear, self-regulation, well-being and agreeableness, are studied without regard to the context in which they occur—with the resulting implication that they mean the same thing across time, cultures and content. They do not.

In his second essay, "Happiness Ascendant," Mr. Kagan virtually demolishes the popular academic effort to measure "subjective well-being," let alone to measure and compare the level of happiness of entire nations. No psychologist, he observes, would accept as reliable your own answer to the question: "How good is your memory?" Whether your answer is "great" or "terrible," you have no way of knowing whether your memory of your memories is accurate. But psychologists, Mr. Kagan argues, are willing to accept people's answer to how happy they are as if it "is an accurate measure of a psychological state whose definition remains fuzzy."

Psychology's Ghosts

By Jerome Kagan

(Yale, 392 pages, $32)

Many people will tell you that having many friends, a fortune or freedom is essential to happiness, but Mr. Kagan believes they are wrong. "A fundamental requirement for feelings of serenity and satisfaction," Mr. Kagan says, is "commitment to a few unquestioned ethical beliefs" and the confidence that one lives in a community and country that promote justice and fair play. "Even four-year-olds have a tantrum," he notes, "if a parent violates their sense of fairness." His diagnosis of the "storm of hostility" felt by Americans on the right and left, and the depression and anomie among so many young people, is that this essential requirement has been frustrated by the bleak events of the past decades. War, corruption, the housing bubble and the financial crisis, not to mention the fact that so many of those responsible have not been held accountable, have eroded optimism, pride and the fundamental need to believe the world is fair.

In the third and fourth essays, "Who Is Mentally Ill?" and "Helping the Mentally Ill," Mr. Kagan turns to the intransigent problems of psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is going ungently into its fifth edition, accompanied by a cacophony of complaints from inside and outside the psychiatric establishment. The DSM "regards every intense bout of sadness or worry, no matter what their origin, as a possible sign of mental disorder," Mr. Kagan laments. But "most of these illness categories are analogous to complaints of headaches or cramps. Physicians can decide on the best treatment for a headache only after they have determined its cause. The symptom alone is an insufficient guide."

Nonetheless, the DSM is primarily a collection of symptoms, overlooking the context in which a symptom such as anxiety or low sexual desire occurs and what it means to an individual. It might mean nothing at all. What it means to an American might mean nothing to a Japanese. The same one-size-fits-all approach plagues treatment: "Most drugs can be likened to a blow on the head," Mr. Kagan observes—they are blunt instruments, not precisely tailored remedies. Psychotherapy depends largely on the client's belief that it will be helpful, which is why all therapies help some people and some people are not helped by any. No experience affects everyone equally—including natural disasters, abuse, having a cruel parent, losing a job or having an illicit affair—though many therapists wish us to believe the opposite.

Mr. Kagan acknowledges that his critiques are not new, that others have made the same arguments—about the failure to consider cultural influences, about the exasperating DSM, about the flaws in happiness research and the negative side of positive psychology, about the medicalizing of normal problems in living. Yet he makes his case persuasively and readably, with extensive empirical support. For a public enamored of looking inward to genes, brain circuits and medications to find solutions to the problems that plague us privately and politically, the message that most of those solutions require us to look outward—to culture, class and context—can't be repeated often enough.

Ms. Tavris, a social psychologist, is co-author, with Elliot Aronson, of "Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)."

A version of this article appeared April 26, 2012, on page A13 in some U.S. editions of The Wall Street Journal, with the headline: Psychology and Its Discontents.