I wrote this paper for class a few months ago. A conversation on Facebook around metaphors for one's therapeutic practice brought this to mind. I might try to expand it into a real paper now that I have more time.

If you are a psychotherapist, or even a coach, what is your metaphor for your practice? Have you thought about it? Would it help orient your work to think more about it?

Therapeutic Narrative and the Metaphor of Counselor Identity

At the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association in1961, Bernard Kaplan claimed that all language is metaphorical (Kaplan, 1981). Traditionally, metaphor has been understood as a function of language, but not every day language—it’s poetic language. George Lakoff, however, has spent most of last thirty years working to revise our understanding of metaphor as the foundation of cognition. He argues that metaphor is more than a form of poetic language unique from everyday language but, rather, “it is a system of metaphor that structures our everyday conceptual system, including most abstract concepts, and that lies behind much of everyday language” (Lakoff, 1992, p. 3). He defines primary metaphor as a function of embodied cognition:

We acquire a large system of primary metaphors automatically and unconsciously simply by functioning in the most ordinary of ways in the everyday world from our earliest years. We have no choice in this. Because of the way neural connections are formed during the period of conflation, we all naturally think using hundreds of primary metaphors. (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999, Kindle locations 626-628)

Lakoff has further argued that most (if not all) metaphors are constructed in relation to the human body, thus the idea of embodied metaphor. His work has overturned some of the theories first proposed by Noam Chomsky, but they are also changing the foundational beliefs of Western philosophy.

For example, the very common and structurally simple class of bodily projections uses in front of and in back of, phrases that rely on the spatial position of the body.

We have inherent fronts and backs. We see from the front, normally move in the direction the front faces, and interact with objects and other people at our fronts. Our backs are opposite our fronts; we don't directly perceive our own backs, we normally don't move backwards, and we don't typically interact with objects and people at our hacks. (Lakoff & Johnson, 1999, Kindle locations 466-468)

The work of Lakoff, with and without Mark Johnson, has over the past several years (1980, 1987, 1992, 1999) served to document the various classes in which metaphors are classified. Lakoff rejects the classical, objectivist view of human cognition, that it exists in an abstract space that may or may not be embodied in a machine, a human brain, or in other living creatures (1987, p. xi). In his model, and that of constructivist psychology and linguistics, “our bodily experience and the way we use imaginative mechanisms are central to how we construct categories to make sense of experience” (Lakoff, p. xii).

Berlin, Olson, Cano, and Engel (1991) fin inspiration in the work of Lakoff and Johnson, building upon the experiential realism model (Lackoff, 1987, p. xv) for understanding human conceptual systems essential to their work on metaphor and psychotherapy (Berlin, et al, p. 360). The conceptual categories approach allows them to identify several metaphors used to describe the therapeutic process. These authors believe that if therapists make an effort to understand how their organizing metaphor of the therapeutic process (which may be unconscious) shapes their work with clients that they will “be more attuned to ways in which metaphors they use highlight certain therapeutic issues and obscure others” (Berlin, et al, 361).

As a developing counselor, I have been looking at the metaphor that guides my work with clients during this first internship period. None of the metaphors mentioned by Berlin and his co-authors seem to fit the model that guides my work, the organizing principles that inform my therapeutic process and shape my experience of the client and my understanding of the work we do. A large part of this process is to understand and take as an object of awareness the narrative in which I make sense of my experience to date.

Jerome Bruner has written several essays on the narrative element of our lives (1995, 1996, 1999, 2004), in fact arguing that narrative is the format that shapes our mind, “recipes for structuring experience”:

I believe that the ways of telling and the ways of conceptualizing that go with them become so habitual that they finally become recipes for structuring experience itself, for laying down routes into memory, for not only guiding the life narrative up to the present but directing it into the future. I have argued that a life as led is inseparable from a life as told—or more bluntly, a life is not "how it was" but how it is interpreted and reinterpreted, told and retold: Freud's psychic reality. (Bruner, 2004, p. 708)

Likewise, the narratives we hold about being counselors and working with our clients can also become an organizing structure for our experience with clients. We see the client’s symptoms, presentation, and our own experience of the client through the lens of that therapeutic metaphor. However, when we fail to be aware of those metaphors that shape our thinking and expectations of the therapeutic process, “situations arise in which different viewpoints occur that are not resolvable by discussion of facts since the important differences involve the metaphorical assumptions” (Berlin, et al, p. 360; Engle, 1988).

Discovering My Own Metaphor

As I looked at the metaphors outlined by Berlin and his co-authors, none of their mechanical models seemed to fit my own internal narrative for the work I try to do with clients. The authors used generative metaphors in their examples, a specific kind of metaphor that “generates” new perspective for framing a problem and conceptualizing solutions.

When a generative metaphor is created, situations that may at first have seemed complex and uncertain become clearer; the diagnosis of the problem and the solutions seem obvious. The new metaphor creates a new logic for solving the problem, new meanings, and ideas for new actions. However, generative metaphors may be totally inappropriate and can obscure important features of what is being described. (Berlin, et al, p. 360)

It’s critical to understand that a seemingly useful metaphor, even a generative metaphor, once it is adopted, limits one’s perceptions to a specific framing of the world, of the idea of therapy, or of the client, as well as of the work we do with our clients. The metaphors they examine, which are likely less common now than they were in the 1980s, include the following (Berlin, et al, 361-364):

- psychotherapy is war (this is based mostly in Freud and some of his early follows), including ideas such as defenses, depression as an enemy, conflict, character armor, powerful allies, and panic attacks, to name only a few

- the mind is a brittle object (an idea that comes from Kohut and Self Psychology), including a focus on the fragility of the mind rather than Freud’s martial metaphors, with words such as breakdown, fragmentation of the self, emotionally disintegrating, feeling shattered, “empathy becomes the glue that repairs the fragmented self” (p. 362)

- somatic metaphors (from the work of Mark Johnson), including themes of balance, embodiment, an unbalanced mind, living out of balance, feeling weighed down, overburdened by life, brilliant observations, visualizations, new perspectives, etc.

- the steam engine metaphor (one of the mechanistic metaphor categories, of which there are undoubtedly others), including simmering anger, anger wells up, feelings boil over, rage erupts, we explode when under too much pressure, and likewise we blow off steam, release the pressure, hold in our feelings, or put the lid on anger

- the conduit metaphor (from the objectivist philosophy that Lakoff rejects), based on three premises, “(1) ideas, meanings, or feelings are objects; (2) linguistic expressions are containers; (3) communication is sending” (p. 363), and including phrases such as put my feelings into words, your feelings are getting through to me, what comes across, unload your feelings in words, uncover the meaning, get into my head, and so on

Of the five metaphors they detail, the conduit metaphor has the deepest implications for the therapeutic relationship. The conduit model describes a world that resides outside the minds of the client and counselor, a world that is expressed and experienced as stable and external with thoughts and ideas that are as physically tangible as a rocking horse or a chair. The assumption is that the words can mirror the world precisely as it is.

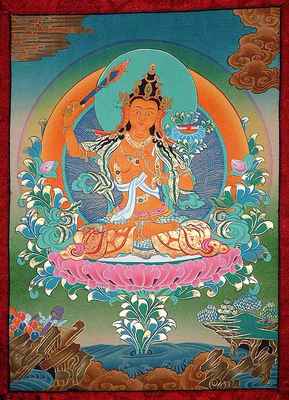

As I read all of this material, I began to explore my own perspective. I come into this process already possessing a pretty clear sense of who I am as a person and who I want to be as a therapist, based partly in my Buddhist practice and partly in my own work in therapy and personal growth. I have no doubt that my views were shaped in part by my early exposure to the Collected Works of Carl Jung (1980) and then to Vedanta-influenced integral philosophy of Ken Wilber (1973, 1980, 1995, 1996, 2000). Both of these authors take a perspective on human beings that conceives of them as essentially good and that dysfunction is matter of wounding and suffering, not of original sin, drives for sex and violence, or inherent flaws. And yet, I hold these views lightly, as guiding principles and not as a topographical map of the therapeutic territory.

The Buddhist approach, as well as the Vedanta in the Hindu model, understands human being as always already perfect at a soul level, or more accurately, as possessing buddhanature. Our dysfunction is seen as a result of our attachments (to things, negative emotions, people, and so on), our emotional and psychological wounding—especially in the Tibetan tradition taught by Pema Chodron (1997, 2005)—and our inability to stay with our feelings when they come up because we are afraid, we don’t know how, or are do not even have much experience of our emotions. All of these are learned behaviors that “cover up” our buddhanature, our inherent psychological and emotional wellness.

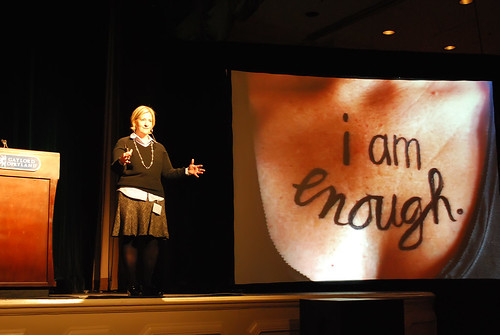

My own model, my own generative metaphor, relies on the concept of uncovering, or retrieval. For example, some common phrases I have noted coming from my mouth in sessions includes the following: reclaiming the self, unearthing the past, finding the exiles, seeking balance, looking for answers, seeking meaning, uncovering the wounds, discovering the selves, and looking for meaning. I’m sure if I worked at it I could come up with many, many more—all of which seeming to rely on the verb actions of uncovering or retrieving.

How the Metaphor Impacts Counseling

I try to approach each new client as a human being who is fully capable of mental health and happiness, and who, no matter the challenges, has a deep hope for happiness and wellness (Sharot, 2011). I would like to believe that this perspective is sensed by the client in my language and use of metaphors regarding dysfunctions. Part of this approach is to normalize symptoms whenever possible and appropriate to reduce their own sense of being broken or damaged.

The use of intersubjectivity theory as a groundwork for the therapeutic alliance allows me to feel more empathy and affective attunement for their situation. This allows me to be nonjudgmental and to seek alignment with their needs and fears. Whatever the modality of therapy (as an integral psychotherapist, I use many modalities and tools, depending on the needs of the client and the situation), I always attempt to be in tune with the client and to convey the sense that we are on a journey of discovery. I have even gone so far as to call the work we do “soul retrieval” with clients who are open to that interpretation.

In the end, I am still learning my craft and how to work with clients most effectively. As I grow as a therapist/counselor, I hope to remain open to the position that my clients are not flawed, only wounded and in need of healing—a healing that always already resided within them and simply needs to be brought forward into their lives.

References

- Berlin, R.M., Olson, M.E., Cano, C.E., and Engel, S. (1991, July). Metaphor and psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychotherapy, Vol. XLV, No. 3: 359-367.

- Bruner, J. (1995). The autobiographical process. Current Sociology, 43, 161-177.

- Bruner, J. (1996). A narrative model of self construction. Psyche & Logos, 17(1), 154-170.

- Bruner, J. (1999). Narratives of aging. Journal of Aging Studies, 13(1), 7-9.

- Bruner, J. (2004, Fall). Life as narrative. Social Research, Vol 71, No 3: 691-710.

- Chödrön, P. (1997). When things fall apart: Heart advice for difficult times. Boston: Shambhala.

- Chödrön, P. (2005). Start where you are: How to accept yourself and others. Boston: Shambhala.

- Engel, S. (1988). Metaphors: How are they different for the poet, the child, and the everyday adult. New Ideas in Psychology, 6:333-41.

- Jung, C.G., with Adler, Gerhard, Fordham, Michael, Read, Herbert, and McGuire, (editors). (1980). Collected works of C.G. Jung: 21 volume hardcover set. Bollingen. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire, and dangerous things: What categories reveal about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G. (1992). The contemporary theory of metaphor. In Metaphor and thought (2nd edition), Ortony, Andrew (ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought (Kindle ed.). Retrieved from www.amazon.com

- Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias: A tour of the irrationally positive brain. NY: Pantheon.

- Wilber, K. (1973). The spectrum of consciousness. Wheaton, IL: Quest Books.

- Wilber, K. (1980). The atman project: A transpersonal view of human development. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical.

- Wilber, K. (1995). Sex, ecology, and spirituality: The spirit of evolution. Boston: Shambhala.

- Wilber, K. (1996). Up from Eden: A transpersonal view of human development. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books.

- Wilber, K. (2000). Integral psychology: Consciousness, spirit, psychology, therapy. Boston: Shambhala.

This work represents an inquiry into the essential nature of human action in all its forms and fields. By human action, I mean to suggest a rather comprehensive scope of inquiry into anything and everything people do, regardless of how conscious or subconscious, purposeful or spontaneous, independent or interdependent these actions might seem. The myriad forms of this human doing—from writing, speaking, and conversing to giving, taking, and trading, to working, playing, and creating to learning, developing, and evolving—serve as creative expressions of, and logical complements to, the equally comprehensive notion of human being. In short, human action encompasses what we do, how we do, why we do, and ultimately who we are as we do.