The Unconscious Politics That Shape Our World, Choose Presidents and Save or Destroy Lives

By Maria Armoudian

There is increasing scientific evidence that human behavior is not rational or conscious, and may be completely programmed without logic or knowledge.April 1, 2010 |

Scientists are finding more and more evidence that human behavior is not rational, not conscious and may be completely programmed without logic or knowledge. These unconscious drives affect jury decisions, elections, wars, our everyday experiences and can sometimes determine life and death. This is the subject of two recent books: Shankar Vedantam's The Hidden Brain: How our Unconscious Minds Elect Presidents, Control Markets, Wage Wars and Save our Lives, and Guillermo Jimenez's Red Genes, Blue Genes, Exposing Political Irrationality. Both demonstrate irrationality but from slightly from different places. We recently discussed these phenomena with the authors.Maria Armoudian: Shankar Vedantam, you open your book with a rape case in which both the victim and the jury and everyone else involved all erred and sent the wrong person to prison -- for 13 years. Why did that happen?

Shankar Vedantam: This is a really tragic story, involving a woman, Toni Gustus, who was raped in Massachusetts. She was a remarkably conscientious eyewitness and took great pains during the crime to memorize the rapist's features. But over the course of the next weeks and months, as police showed her images of people whom they thought might be potential suspects, her memory of the case degraded, and she was pretty sure the police had the right person. But there was a little bit of a doubt at the back of her mind. When she spent that Christmas with her family at a church that had long been a source of comfort and solace, her doubt slipped away, and she told herself that she had gotten the man.

As it turned out, a DNA test conducted about a decade later showed that this man could not have been the criminal. The point, of course, is that we regularly think that people's intentions are decisive, that if someone means to be a good eyewitness or a good juror, judge or politician, that they are a good juror, judge or politician. It turns out that there is much in our lives that lies outside the boundaries of our conscious awareness, and in this church where Toni Gustus' doubts slipped away, in some ways reassurance and solace were not her friends in this situation. Her doubt at the back of her mind was actually her friend because it was telling her something is not quite right about this situation.

MA: So her emotions over the course of the investigation and in that particular environment -- the church -- ultimately led her to make the misjudgment?

SV: I think that's right. The ironic thing is that you can see why it would be most understandable for her to seek a situation where she was comforted and had some solace, but she was also in a situation where she was being asked to make a very difficult judgment. So without her intending to make a mistake, and with her intending to do things exactly right, she made this mistake. And she was a really conscientious, diligent person, someone whom I respect and regard very highly, so if this mistake can happen to Toni Gustus it can happen to any of us.

MA: Similarly, you point out the unconscious roles with race and gender. Even when people are conscientiously trying not to have prejudices, they are still programmed and affect us.

SV: Yes, the unconscious bias affects our romantic decisions, our financial decisions, our moral decisions, our political decisions. One of the domains is the question of unconscious prejudice. The striking thing here is that we pay a lot of attention to hate crimes or people who explicitly say racist things or sexist things. But it turns out that at an unconscious level, prejudice exists in very large numbers of people, perhaps even among most people. These effects are subtle; they're not the person who is burning a cross on someone else's lawn. This is a person who may have an unconscious association in [his or her] head. But when asked to make a decision about whether somebody is guilty or innocent of a crime, or whether to hire someone for a job, these unconscious associations play very powerful roles, especially because most people do not believe the unconscious exists. And so we have no way to guard against the manipulation because we don't even realize that we're being manipulated.

MA: One of the most convincing parts of your book dealing with gender bias was the experiences of transgendered people. People who transgendered from women to men suddenly -- although the same person, same qualifications, same education -- had a better income, opportunity and less interruptions.

SV: That's right. There is abundant research showing that, on average, women are not paid the same as men and face all kinds of challenges compared to men. But when you're asked to make a judgment about any individual person -- say Hillary Clinton in the 2008 presidential election -- it's very difficult to apply the general research on bias to an individual, because with any individual circumstance, there are many other factors: How good a candidate is Hillary Clinton, what are her positions on the issues; what's the competition like? And so on.But there was a group of people who are their own control groups -- those who are transgendered. Research shows that when men transitioned to being women, their hourly salaries dropped, often quite dramatically. When women transitioned to being men, their hourly salaries on average rise. But the real effects of sexism are actually much more subtle than salary. Men who become women experience losses of all kinds of privileges that they didn't know they had, and women who become men experience the relief of being carried by a current that they didn't even know existed, and that's stronger than them.

MA: One other phenomenon pertained to the bystander effects whereby crowds, in some cases, do nothing to stop torture and even murder. But you said that if one person stands up, the crowd might move. What is that phenomenon?

SV: There are many cases showing that often when terrible things unfold we intuitively believe that it's a good thing to have many people around, because if there are many people then surely there will be some good Samaritans among them. It turns out that the opposite is true, that you're more likely to have people come to your aid when there are a few people rather than many people. But the bystander effect doesn't just affect our ability to act in the service of other people; it affects our ability to act in the service of ourselves. Groups rob us of our autonomy and our ability to act in intentional ways. And there is very compelling research, for example, showing that these forces played a very large role in the events that unfolded on the morning of September 11, 2001, in the south tower of the World Trade Center in particular.

MA: How?

SV: The south tower was the second tower to be hit that awful morning. And there was a 15-minute window between when the first tower was hit and the second tower was hit. Nearly everyone on one floor escaped the building and survived, whereas nearly everyone on the other floor stayed behind in their building and perished. The point is that in crisis, people tend to act together. They are either silent together or they act together; they intervene together or they're passive together; they either flee together or they stay at their desks together. The lack of autonomy from groups has great consequences.

MA: Now on political rationality, Guillermo Jimenez also argues that there are possible genetic explanations, specifically with political decisions, sort of a biological predisposition toward political proclivities. Guillermo?

Guillermo Jimenez: One of the arguments that I make is that most of us are born somewhere along a left to right political disposition that influences our political orientation throughout our lives, much like what Shankar is talking about. The great majority of us have some political bias, but we tend to not perceive it because it lies in the unconscious. And we have a lot of techniques of self-deception to prevent it from rising to our consciousness. At the same time, we perceive it very well in the other party.That's one of the funny things about irrationality -- that we can see it in others but not in ourselves. The Fox TV commentator Glenn Beck for me is the incarnation of political irrationality, from the liberal perspective. It's hard for a liberal to watch Glenn Beck without coming to the conclusion that the man is unhinged. He's so obviously biased that anything that Obama or a Democratic administration does, he will criticize. He doesn't perceive that bias, but liberals do. But liberals are not immune to this kind of irrationality.

MA: You describe the reaction that we sometimes have, when they watch their political opposite. The experience is that from every fiber of one's being -- the opponent's hair, his tie, the way he speaks, his accent -- makes us recoil. You said, in essence, his DNA really upsets our DNA -- and that this is prevalent on both sides, driven by a number of phenomena, partly genetically But how much of it is conditioning by the polarized media? And how much is biologically based?

GJ: There is incredible groundbreaking research in the field of the biological bases of political dispositions. In one experiment, a group of people identified as very liberal or very conservative through questionnaires -- when they were exposed to startling stimuli like loud noises, gruesome photographs -- they had very different involuntary responses. People who are more instinctively fearful tend to have more conservative political orientations and more likely to support defense spending, the Iraq war, capital punishment, patriotism. People who showed a calmer or less fearful instinctive response were more likely to support pacifism, liberal immigration policies, foreign aid and so forth. The [involuntary responses] suggest that there is a biological component, which may be slight, but it is present and detectable in our political opinions. But we don't perceive it ourselves.We think that we come to our political opinions through some exercise of logic or reason. I argue that it's about 50 percent genetics. Then on top of that genetic layer, we have a cultural layer which reinforces biases and prejudices. So most of us end up doubly prejudiced or biased in our politics, partially from our biological inheritance and partially from our social upbringing.

SV: What I find fascinating about our divide is twofold: First, why is it so much more intense today than it was, say 50 years or 100 years ago? Our biology hasn't changed, but if you look at the number of Democrats who are passionately against a Republican president and vice-versa. The gap is just extraordinary today compared to what it was 100 years ago.And the other thing that I find really intriguing is that many of the issues that divide liberals and conservatives don't fall along what you would call logical patterns. So for example, conservatives are against government intervention in general; they want a hands-off, laissez faire policy, but when it comes to abortion or family values issues they want a very interventionist government policy. They want a government to be involved in running people's lives or telling people what's appropriate and inappropriate.

I'm not saying that one side is hypocritical, because I think Guillermo is right in terms of saying that both sides are guilty of this. But why don't people see these inconsistencies themselves? When you're on one side, there's nothing that your side can do that feels wrong, and there's nothing on the other side that can do that feels right.

Research from political science argues that in many ways, the driver behind partisanship is the same driver that's behind our passion for our sports teams. When I think about it, it's absurd to be a fan of any single football team, because these are players who are interchangeably going between the different teams, yet they just happen to be wearing one set of colors. But when I'm watching the game, my team can do no wrong, and every ambiguous call that the referees make, I say well they made a mistake and they should have given it to [my team]. I think the same thing is happening at the political level, that we identify with a party in the same way we identify with sports teams, and that, in some ways, causes us to fail to see the inconsistencies of our own position and fail to see the weaknesses in our side or any good in the other side.

MA: There is research done in political psychology showing that membership in any group, even if it's completely arbitrary, automatically creates an us and a them, and a sense of competition. Perhaps that's a missing element and that's the thing that needs to be understood.

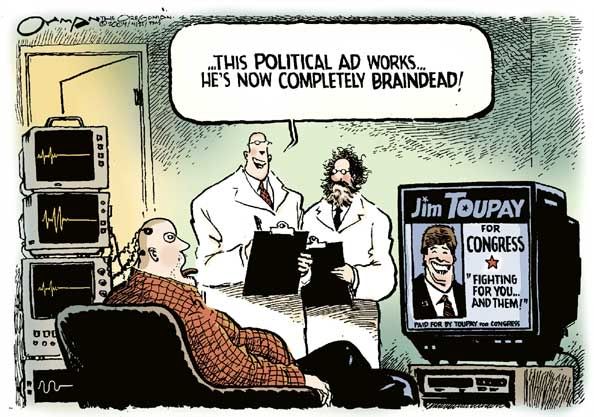

GJ: The symbol of the sporting contest is a great one. In psychology research, students who are randomly assigned to be for one or the other team and watch a game within minutes become very biased in favor of that team.But to the other question: Why is it increasing? There are a number of reasons. Political scientists have found that polarization in Congress increases in times of economic stress. Also when we're trying to rewrite our fundamental social contracts, it makes sense that we would become more polarized. So while health care reform is on the table -- it's something we've been working on for 40 or 50 years that will change our country -- it's natural that you will have some polarization. On top of that is modern media and the Internet. Nowadays we can get all of our information from biased news sources. A lot of people that watch Fox News, then read the Wall Street Journal and Ann Coulter's books, are not going to get a fair or balanced view of reality. On top of that, you add the media circus, which makes money from conflict. They get eyeballs to their shows by presenting divisive political figures that rile up our emotions and get us glued to the TVs. So we have a number of factors working together which have given us this perfect storm of polarization.

MA: Guillermo, you say fear and loathing are the most dangerous parts of political irrationality. Why?

GJ: We have to be wary of political appeals to fear and to hatred. On the liberal side, we don't have a lot of appeals to hatred, maybe we did during the Bush era. There were a lot of liberals that hated George Bush. But now on both sides, our politicians attract our attention by creating fear in us. Liberals can be as guilty of this as conservatives. Conservatives present a frightening picture of liberal sadists who want to control your very life; and liberals present this counter-portrait of hateful, racist, corporate, warmongering conservatives. And the result is not a happy one for our political environment in general.

MA: That reminds me of something Shankar wrote about regarding terrorism and extremism, particularly that there is no real psychological profile that's different between a suicide bomber and somebody else. What does that mean for us?SV: Well, although it seems as if terrorists should come from dysfunctional backgrounds or have dysfunctional personalities, there has been systematic research conducted among people who attempted to be suicide bombers with failed missions and who are now in prisons, that they are hardly more aberrational than the rest of us. It's not the case that they're more religious than the rest of us. If you look at the history of suicide terrorism, religion turns out to be neither necessary nor sufficient as an explanatory factor for suicide terrorism.

What is common to suicide terrorism in different eras as far back as the Japanese Kamikaze bombers during World War II is that suicide terrorists typically are formed in an environment where they're essentially cut off from the outside world, whereas in our normal lives, most of us get pulled in different directions, which creates conflict. We have ties to our families, churches, sports teams and professions. But the suicide bomber goes into what I call the tunnel in which the person doesn't face the conflicts of the outside world. All of the reference points within the tunnel are the reference points created by people within their own group. Then a dynamic called small-group psychology that takes over. Small-group psychology can change the norms f what's good and bad behavior. So what seem aberrational to us outside the tunnel can become aspirational to people within the tunnel.

Maria Armoudian is a journalist, singer/songwriter and legislative consultant whose articles have been syndicated by the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times syndicates. She has written for Salon.com, Daily Variety, Billboard, the Progressive and Business Week among others.

MA: It is reminiscent of Zimbardo's Lucifer effect. Guillermo, how do these take us to war and how are these seen differently between liberals and conservatives?

GJ: Daniel Kahneman, who won the Nobel Prize in 2002, developed the whole modern theory of cognitive bias in his article, "Why Hawks Win." He observed that most cognitive biases that we've discovered in the last 40 years tend to favor a militaristic warlike approach. The conduct of leaders as we lead up to war impacts the most common cognitive biases. The classic example is the Iraq war and the common bias of being overconfident. So there was Vice-President Cheney predicting that American soldiers would be welcomed in Iraq as liberators, and anybody who's read the news and what's going on in Iraq the last months knows that that was never the case. That's just one example of how bias can cause our leaders to go to war.