Like there was ever any doubt.

Offering multiple perspectives from many fields of human inquiry that may move all of us toward a more integrated understanding of who we are as conscious beings.

Pages

Saturday, July 26, 2008

Fox News Works for The White House

Like there was ever any doubt.

How the Mind Works: Revelations

The article focuses on the work of Jean-Pierre Changeux, the leading French neuroscientist, whose current research centers in the reward centers of the brain and how these structures and neurotransmitters shape consciousness.

Here is a key quote from later in the article, one that sounds mightily Buddhist:

In fact, "external reality" is a construction of the brain. Our senses are confronted by a chaotic, constantly changing world that has no labels, and the brain must make sense of that chaos. It is the brain's correlations of sensory information that create the knowledge we have about our surroundings, such as the sounds of words and music, the images we see in paintings and photographs, the colors we perceive: "perception is not merely a reflection of immediate input," Edelman and Tononi write, "but involves a construction or a comparison by the brain."So, physical reality is constructed in our brains? Didn't Buddha say that same thing about 2,500 years ago? The stuff is mind-bogglingly cool.For example, contrary to our visual experience, there are no colors in the world, only electromagnetic waves of many frequencies. The brain compares the amount of light reflected in the long (red), middle (green), and short (blue) wavelengths, and from these comparisons creates the colors we see. The amount of light reflected by a particular surface—a table, for example— depends on the frequency and the intensity of the light hitting the surface; some surfaces reflect more short-wave frequencies, others more long-wave frequencies. If we could not compare the presence of these wavelengths and were aware of only the individual frequencies of light—each of which would be seen as gray, the darkness or lightness of each frequency depending on the intensity of the light hitting the surface—then the normally changing frequencies and intensities of daylight (as during sunrise, or when a cloud momentarily blocks out the sun) would create a confusing picture of changing grays. Our visual worlds are stabilized because the brain, through color perception, simplifies the environment by comparing the amounts of lightness and darkness in the different frequencies from moment to moment.[3]

How the Mind Works: RevelationsRead the whole article.By Israel Rosenfield, Edward Ziff

The Physiology of Truth: Neuroscience and Human Knowledge

by Jean-Pierre Changeux, translated from the French by M.B. DeBevoise

Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 324 pp., $51.50

Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptors: From Molecular Biology to Cognition

by Jean-Pierre Changeux and Stuart J. Edelstein

Odile Jacob, 284 pp., $99.00

Conversations on Mind, Matter, and Mathematics

by Jean-Pierre Changeux and Alain Connes, translated from the French by M.B. DeBevoise

Princeton University Press,260 pp., $26.95 (paper)

What Makes Us Think? A Neuroscientist and a Philosopher Argue about Ethics, Human Nature, and the Brain

by Jean-Pierre Changeux and Paul Ricoeur, translated from the French by M.B. DeBevoise

Princeton University Press,335 pp., $24.95 (paper)

Phantoms in the Brain: Probing the Mysteries of the Human Mind

by V.S. Ramachandran and Sandra Blakeslee, with a foreword by Oliver Sacks

Quill, 328 pp., $16.00 (paper)

Mirrors in the Brain: How Our Minds Share Actions and and Emotions

by Giacomo Rizzolatti and Corrado Sinigaglia, translated from the Italian by Frances Anderson

Oxford University Press,242 pp., $49.95

A Universe of Consciousness: How Matter Becomes Imagination

by Gerald M. Edelman and Giulio Tononi

Basic Books, 274 pp., $18.00 (paper)

Jean-Pierre Changeux is France's most famous neuroscientist. Though less well known in the United States, he has directed a famous laboratory at the Pasteur Institute for more than thirty years, taught as a professor at the Collège de France, and written a number of works exploring "the neurobiology of meaning." Aside from his own books, Changeux has published two wide-ranging dialogues about mind and matter, one with the mathematician Alain Connes and the other with the late French philosopher Paul Ricoeur.

Changeux came of age at a fortunate time. Born in 1936, he began his studies when the advent both of the DNA age and of high-resolution images of the brain heralded a series of impressive breakthroughs. Changeux took part in one such advance in 1965 when, together with Jacques Monod and Jeffries Wyman, he established an important model of protein interactions in bacteria, which, when applied to the brain, became crucial for understanding the behavior of neurons. Since that time, Changeux has written a number of books exploring the functions of the brain.

The brain is of course tremendously complex: a bundle of some hundred billion neurons, or nerve cells, each sharing as many as ten thousand connections with other neurons. But at its most fundamental level, the neuron, the brain's structure is not difficult to grasp. A large crown of little branches, known as "dendrites," extends above the body of the cell and receives signals from other neurons, while a long trunk or "axon," which conducts neural messages, projects below, occasionally shooting off to connect with other neurons. The structure of the neuron naturally lends itself to comparison with the branches, trunk, and roots of a tree, and indeed the technical term for the growth of dendrites is "arborization." (See the illustration below.)

We've known since the early nineteenth century that neurons use electricity to send signals through the body. But a remarkable experiment by Hermann von Hermholtz in 1859 showed that the nervous system, rather than telegraphing messages between muscles and brain, functions far slower than copper wires. As Changeux writes,

Everyday experience leads us to suppose that thoughts pass through the mind with a rapidity that defies the laws of physics. It comes as a stunning surprise to discover that almost the exact opposite is true: the brain is slow—very slow— by comparison with the fundamental forces of the physical world.Further research by the great Spanish anatomist Santiago Ramon y Cajal suggested why the telegraph analogy failed to hold: most neurons, instead of tying their ends together like spliced wires, leave a gap between the terminus of the neuron, which transmits signals, and the receptor of those signals in the adjacent neuron. How signals from neurons manage to cross this gap, later renamed the synaptic cleft ("synapse" deriving from the Greek for "to bind together"), became the major neurophysiological question of the early twentieth century.

Most leading biologists at that time assumed that neurons would use the electricity in the nervous system to send signals across the cleft. The average synaptic cleft is extremely small—a mere twenty nanometers wide—and though the nervous system may not function at telegraphic speed, it was not difficult to imagine electrical pulses jumping the distance. Further, given the speed with which nerves react, the alternative theory, that electrical pulses would cause a chemical signal to move across the cleft, seemed to rely on far too slow a mechanism. But as the decades passed, hard evidence slowly accumulated in support of the chemical theory. According to Changeux, experiments began to suggest that "the human brain therefore does not make optimal use of the resources of the physical world; it makes do instead with components inherited from simpler organisms...that have survived over the course of biological evolution."

A remarkable experiment by Otto Loewi in the 1920s first suggested how the brain makes use of its evolutionary inheritance in order to communicate. Loewi bathed a frog's heart in saline solution and stimulated the nerve that normally slows the heartbeat. If the slowing of the heart was caused by a chemical agent rather than an electrical impulse, Loewi reasoned, then the transmitting chemical would disperse throughout the solution. Loewi tested his hypothesis by placing a second heart in the solution. If nerve transmission was chemical rather than electrical, he supposed, then the chemical slowing down the first heart, dispersed throughout the solution, would likewise slow down the second heart. This is exactly what happened. Loewi named the substance released by the relevant nerve, called the vagus nerve, Vagusstoff; today it is known as the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. By the 1950s, further experiments had definitively proved that most neurons, while using electricity internally, must resort to chemicals to cross the synaptic cleft and communicate with the next neuron in the chain.

Changeux began his work at this stage, when the basic methods for neuron communication had been determined but the detailed chemical mechanisms were just opening up to research. Thanks to new high-resolution images from electron microscopes, first taken by Sanford Palay and George Palade in 1955, biologists could finally see the minute structures of the synapse. They discovered that the transmitting end of the neuron, called the nerve terminal, comes packed with tiny sacs, or vesicles, each containing around five thousand molecules of a specialized chemical, the neurotransmitter. When an electrical signal moves down the neuron, it triggers the vesicles and floods the synaptic cleft with neurotransmitter molecules. These chemical neurotransmitters then attach to the proteins called receptors on the surface of the neuron that is located just across the synaptic cleft, opening a pore and allowing the electrically charged atoms called ions to flow into the neuron. Thus, the chemical signal is converted back into an electrical signal, and the message is passed down the line.

These processes were still somewhat mysterious in 1965, when the young Changeux, working with his teacher Jacques Monod and the American scientist Jeffries Wyman, produced one of the theories for which he became best known. The three scientists, then studying metabolism, attempted to explain how the structure of an enzyme could stabilize when another molecule attached to it. Changeux later saw a parallel with the nervous system. When a chemical neurotransmitter binds to a receptor it holds the ion pore open, ensuring its continuing function, a critical step in converting the neurotransmitter's chemical signal back into an electrical pulse. Changeux's discovery established the groundwork for the way many neurons communicate, and his findings were based on the more general paper he had coauthored with Wyman and Monod.

With a working theory for neuron communication established, Changeux then turned to the ways that larger structures in the brain might change these basic interactions. A longstanding theory, introduced by Donald Hebb in 1949, proposed that neurons could increase the strength of their connection through repeated signals. According to a slogan describing the theory, "neurons that fire together, wire together." Repeated neuron firings, Hebb believed, would produce stronger memories, or faster thought patterns. But researchers found that certain regulatory networks could achieve far more widespread effects by distributing specialized neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and acetylcholine, throughout entire sections of the brain, reinforcing connections without the repeated firings required by Hebb.

Changeux focused on these specialized distribution networks. It was long known that nicotine acts on the same receptor as the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. Changeux recognized that this could explain both nicotine's obvious benefits—greater concentration, relaxation, etc.—as well as the drug's more puzzling long-term effects. For instance, while cigarettes are dangerous to health, some studies show that smokers tend to suffer at significantly lower rates from Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Changeux found that nicotine, by attaching to the same receptors as acetylcholine, reproduces some of the benefits of acetylcholine by reinforcing neuronal connections throughout the brain. Nicotine is not exactly the same chemically as acetylcholine, but can mimic its effects. Changeux's lab has since focused on the workings of the nicotine/acetylcholine system, and he has attempted to explain how all such regulatory systems, working together, can produce the experience we call consciousness—as well as more abstract concepts like truth.

Daily Dharma - One Mind to Rule Them All

Today's Daily Dharma from Tricycle:

One Mind to Rule Them All. . .The five spiritual faculties--faith, energy, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom--are our greatest friends and allies on this journey of understanding. These qualities are most powerful when they are in balance. Faith needs to be balanced with wisdom, so that faith is not blind and wisdom is not shallow or hypocritical. When wisdom outstrips faith, we can develop a pattern where we know something, and even know it deeply from our experience, yet do not live it. Faith brings the quality of commitment to our understanding. Energy needs to be balanced with concentration; effort will bring lucidity, clarity, and energy to the mind, which concentration balances with calmness and depth. An unbalanced effort makes us restless and scattered, and too much concentration that is not energized comes close to torpor and sleep. Mindfulness is the factor that balances all these and is therefore always beneficial.

~ Joseph Goldstein, in Seeking the Heart of Wisdom: from Everyday Mind, edited by Jean Smith, a Tricycle book.

Friday, July 25, 2008

More Psychology Books

First up, from The Wall Street Journal:

The Synapse and the SoulRead the rest of the review.By ADAM KEIPER

July 8, 2008; Page A19![[The Synapse and the Soul]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/ED-AH838_brhuma_20080707122959.jpg)

Human

By Michael S. Gazzaniga

(Ecco, 447 pages, $27.50)What is it that makes us human – that sets us apart from other animals? What drives us to act altruistically? Why do we gossip and flirt and empathize? How do we judge beauty, and why are we impelled to create works of art?

In "Human: The Science Behind What Makes Us Unique," Michael S. Gazzaniga argues that modern neuroscience is on the brink of offering us real answers to these questions – answers more reliable and truthful than those that centuries of philosophy, religious tradition and literature have offered. Thanks to advances in brain research, Mr. Gazzaniga believes, "things have changed." We can at last set aside vague speculation and get down to facts. We can finally understand love and courtship and the roots of morality. We can put an end to the "long windbag discussions about art." If we want answers, science has them.

What science tells us is simple and, by now, familiar: Who we are today is the result of eons of evolutionary adaptations serving our basic biological impulses to survive and reproduce. Evolutionary pressures shaped our bodies and minds as well as our social behaviors. There is almost nothing in human social life, Mr. Gazzaniga says, that cannot ultimately be explained by recourse to evolution.

The next few reviews are all from Metapsychology Online Reviews.

Traumatizing Theory: The Cultural Politics of Affect in and Beyond Psychoanalysis

by Karyn Ball

Other Press, 2007

Review by Petar Jevremovic

This interesting book could be seen as a collection of eleven really insightful (and of course, potentially enriching) essays that are mainly concerned with the different possible aspects of the trauma. It is not just another theory of trauma. It is also far from being jusst a collection of various theories of the trauma. It is more a collection of eleventh different theoretical attempts to theorize trauma. To make it discursively present. To make it (paradoxically) theoretic. Grounded in history, philosophy and (broadly speaking) culture, this book embraces important philosophers such as Kierkegaard, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Levinas s well as theorist such as Derrida, Foucault, Lyotard and Deleuze. In this book there is also a lot of psychoanalysis, and even politics.It a is well known fact -- therapists know it quite well -- that it is almost absolutely impossible to think, write and talk about traumatizing causes and effect of trauma. There is something deeply mute, alogic and inhuman in the bottom of traumatic experience. There is something essentially atheoretic within the traumatic experience. There is no place for metaphor within the traumatized subjectivity. Traumatic core of traumatic experience is beyond any symbolization and ideation (or we could say mentalization). Trauma is something ontologically unmediated. One of its logical consequences is (just mentioned) trauma’s atheoretic essence. There is no place for any symbol within it. There is no functional ideation. The traumatized subject is deeply frozen in unbearable reality (reality that is not symbolized and not mentalized) of his primitive mental state.Read the rest of this review.

Dialogues on Difference: Studies of Diversity in the Therapeutic Relationship

by J. Christopher Muran (Editor)

American Psychological Association, 2006

Review by Anca Gheaus, Ph.D.

Psychotherapy is often perceived as diminishing our capacity to criticize the world and uncover its many forms of injustice. After all, its goal is to empower clients to deal better with life's challenges, to pursue their dreams more efficiently, or, at very least, to accept and to cope with the world while leading lives as functional as possible. As Freud put it a long time ago, psychotherapy is supposed to enable people to love and work. An obvious hindrance to this project is blaming one's problems on the external world -- with its unfair institutions, cruel traditions and mischievous or evil others. Indeed, in order to (re)gain due power over one's life, one has to take responsibility for what happens to oneself as well as for how one is responding to external events. To focus on changing one's own self, one might need to take away one's energy and attention from what is wrong with, and what should change in, the world.These truths, however, do not take away the fact that we are living in an unjust world, shaped by various legacies of marginalizing, oppressing and discriminating against many groups of people. Gender, race, class, sexual identity, age, bodily and intellectual ability as well as being a migrant are embedded in one's identity as well as in the way in which we live our psychological impasses. To complicate things further, these identities often intersect and many individuals have to live with multiple, and complexly interacting, histories of social exclusion. For a long time, psychoanalysis as well as other schools of psychotherapy have obscured or, even worse, mystified issues related to social exclusion and turned a blind eye to the many injustices involved in defining "normality" and "functionality". One of the best known examples is the long history of pathologizing and medicalizing homosexuality within psychoanalysis. The book edited by Cristopher Muran provides both an illustration of the recent turn, within psychotherapy, towards integrating and engaging previously ignored questions concerning difference, and an invitation to reflect on how this turn has affected both psychological theory and practice.Read the rest of this review.

Polarities of Experiences: Relatedness and Self-definition in Personality Development, Psychopathology and the Therapeutic Process

by Sidney J. Blatt

American Psychological Association, 2008

Review by Edmund O'Toole

Sidney Blatt has had a distinguished career as a psychologist and he has written extensively on personality and psychopathology, receiving many accolades for his work. He has contributed enormously to psychiatry and psychology, both clinically and academically. Polarities of Experience is a scholarly work examining the development of personality through self-definition and relatedness. Blatt offers self-definition and relatedness as fundamental tensions in the development of personality and considers this approach to have enormous relevance for psychopathology; this is supported by clinical and empirical research. Throughout the book Blatt offers a number of diagrams and scales to effectively elucidate the theoretical understanding of this approach.Read the rest of this review.

In terms of the philosophy of psychology, many of the issues he presents are also essential for an understanding of intersubjectivity as a subject. Philosophers have traditionally tended to deal with intersubjective experiences but Blatt manages to consolidate theoretical and empirical methodology in a creditable way that reinvigorates the need to address the issues practically. Redefining psychopathology in terms of the fundamental dimensions may prove beneficial in the amelioration of many of the problems and criticisms which have beset the contemporary psychiatric approach. Indeed, empirical evidence has been gathering for quite some time highlighting the need to discriminate depression and other personality disorders along anaclitic and introjective dimensions. From his perspective most personality theories can be divided along the lines of an emphasis on separatedness or relatedness. Maladaptive features may arise at any development level of personality stemming from an over emphasis upon either dimension which threatens personality integration.

Embracing Mind: The Common Ground of Science and Spirituality

by B. Alan Wallace and Brian Hodel

Shambhala, 2008

Review by Natalie F. Banner

In Embracing Mind Wallace and Hodel attempt to reconcile the typically Western approach to a science of the mind with Buddhist contemplative methods of investigating consciousness. They are critical of the apparent predominance of scientific materialism but aim to draw significant parallels between the theorizing of contemporary physics and Buddhist metaphysics, arguing that there is much to be gained from a fruitful dialogue between the two. The book assumes little or no previous knowledge either of the history and philosophy of science or of contemplative approaches to the mind and world and as such is well targeted towards a lay audience with an interest in gaining a tentative insight into the potential crossover between Eastern and Western empirical traditions.Read the rest of this review.

The book is divided into three parts, of which this review will focus on the first two. This is because the latter part is an introduction for the curious to three meditative Buddhist practices; effectively the tools of a Buddhist science of contemplation. As a description of the methods of Buddhist meditation this section is not amenable to critical analysis by a reviewer ignorant of such traditions.

The main bulk of the book is devoted to the argument that a Western approach to science in general and a science of the mind more specifically has ignored the role of the mind itself. In focusing outwards on what is present or real in the external world, we have apparently overlooked the vital role of introspection in understanding not only our own minds but the universe of which we are part. The text is structured so as to guide the reader from the unquestioning acceptance of a powerful lay conception of science through to an acknowledgement of the errors and shortcomings of this perspective, before introducing a plausible rhetoric about the advantages a Buddhist metaphysics can provide. It is not intended as an invective against science or scientific practice but rather an exploration of the limitations certain deep-rooted assumptions have for understanding and investigating the mind and world, and a gesture towards possible collaboration between science and spiritual traditions.

Escape Your Own Prison: Why We Need Spirituality and Psychology to be Truly Free

by Bernard Starr

Rowman & Littlefield, 2007

Review by Melanie Mineo

In Escape Your Own Prison: Why We Need Spirituality and Psychology To Be Truly Free, Bernard Starr's purpose is twofold: first, translate Eastern spiritual teachings "into basic principles of consciousness, reality, and self that could be fully expressed and practiced in a Western mode" (xi); and second, develop, articulate, and advance a new omni consciousness psychology based on these principles.

Central to Starr's effort is the psycho-spiritual reclamation of our 'genuine self', a form of consciousness that "we all own but abandon early in life" (xi), albeit unintentionally. Starr reports that this disaffection of our genuine, or real self begins with the onset of 'psychological birth' (i.e. with the separation-individuation developmental process). The newborn 'I/me' emerges from the womb of symbiotic consciousness, and so begins the seeding of the 'ego self'. As we grow and mature, this 'ego self' has the propensity to completely eclipse the real self--'the original face we are born with'--through a heaping on of socio-cultural accretions that, though necessary for survival and the successful navigation of the commons of our shared social world, can be alienating, and generally deleterious to our continued flourishing, if allowed to trap and imprison us.

Veganism Is Murder

As a confirmed omnivore, I get a little tired of hearing how my diet is needlessly killing animals, and killing the planet to boot.

Jill Richardson answers the second point for me -- I am trying to find ways to get my meat (mostly chicken) from local, environmentally conscious sources (this would be easier if I ate more beef, strangely enough).

Be sure to go read the rest of her Open Letter to Al Gore.A friend of mine, Judith McGeary, produces sustainable lamb, chicken, turkey, and eggs on her small Texas farm. The sheep graze on pasture, harvesting their own food. Judith tries to source feed for the chickens and turkeys locally when possible.

Most of all, the farm represents an enormous carbon sink. Instead of collecting manure in polluting, smelly lagoons like a factory farm, Judith lets nature take its course. Dung beetles on her land take care of all of the manure and they improve the soil at the same time. Then she sells the meat to local customers who use little oil to transport the meat home. She uses a lot of energy for refrigeration but she offsets it with solar panels on her roof. Her new home, currently under construction, will be a green building.

Judith is a scientist and an environmentalist. She earned a degree in Biology from Stanford, a JD from UT-Austin, and she also studies graduate level eco-agriculture at UT-Austin. Thousands like her around the country are equally passionate about sustainable agriculture. They might not all have degrees from Stanford but they aren’t starry eyed, idealistic hippies either.

The more annoying -- and hypocritical -- condemnation of my diet comes from the fiercely antagonistic (and often outright deceptive) folks at PETA. But Wesley J. Smith, writing at The National Review, has posted a great answer to their animal rights arguments.

Veganism Is MurderMy guess is that I would disagree with this man on most issues, but on this one point I am mostly in agreement.

If God didn't want us to eat cows, he wouldn’t have made them out of steak.

By Wesley J. Smith

PETA — People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals — is at it again. When actress Jessica Simpson recently wore a T-shirt bearing the words “Real Girls Eat Meat,” the animal-rights zealots pounced. “Jessica Simpson might have a right to wear what she wants,” a PETA spokesperson said, “but she doesn’t have a right to eat what she wants — eating meat is about suffering and death.”

Listening to animal-rights activists bray on about the wrongness of slaughtering animals for food — summarized in their advocacy phrase “meat is murder” — one would think that the choice we have is between a diet in which animals are killed and a strictly vegan diet involving no animal deaths.

But life is never that simple: Plant agriculture results each year in the mass slaughter of countless animals, including rabbits, gophers, mice, birds, snakes, and other field creatures. These animals are killed during harvesting, and in the various mechanized farming processes that produce wheat, corn, rice, soybeans, and other staples of vegan diets. And that doesn’t include the countless rats and mice poisoned in grain elevators, or the animals that die from loss of habitat cleared for agricultural use.

Animal-rights activists certainly don’t mention this inconvenient fact in their advocacy materials. But if the matter comes up in debate, they have a problem: They believe it is “speciesist” to grant some sentient animals — including humans — greater value than others; as PETA’s Ingrid Newkirk so famously put it, “a rat, is a fish, is a dog, is a boy.” Thus, they cannot contend that it is more wrong to kill a pig than a rabbit. Nor can they argue that field animals experience less-agonizing deaths from plant agriculture than food animals do from food-animal slaughtering. Field animals may flee in panic as the great rumbling harvest combines approach, only to be shredded to bits within their merciless blades; they may be burned to death when field leavings are burned; they may be poisoned by pesticides; they may die from predation when their plant cover has been removed.

No question: The animal-rights forces hold a weak intellectual hand.

I asked an animal-rights leader, Rutgers law professor Gary Francione, what he thought about this. He claimed that the key issue is intent:Francione also claimed that omnivores occasion a far greater animal-death toll than vegans: “It takes 3 ¼ acres to feed an omnivore for a year; 20 vegans can be fed from that same space. Therefore, to the extent that there is harm caused to sentient beings by the production of plants, that harm is only multiplied by the omnivore.”Forget about animals. The very same situation exists with respect to humans. We build roads knowing that people will die; we raise speed limits knowing that an additional 10 miles means X deaths. . . . There is an enormous difference between harm that happens that we do not intend to occur and that which we intend. We should obviously endeavor to commit as little harm as possible but we cannot eliminate harm. We can, however, eliminate intentional harm. And eating animals involves an intentional decision to participate in the suffering and death of nonhumans where there is no plausible moral justification.

But neither “intent” (as Francione defines it) nor utilitarian comparison of the carnage is the real issue. The argument made by animal-rights activists is that meat is murder, while veganism is supposedly cruelty-free.

Moreover, even if the relative number of animals killed were the morally decisive issue, veganism might not be the most ethical solution. In 2001, S. L. Davis of the Department of Animal Sciences at Oregon State University, Corvallis, wrote a paper claiming that the diet most likely to result in the deaths of the fewest animals would be beef, lamb, and dairy — not vegan. Davis found a study that measured mouse population density per hectare in grain fields both before and after harvest and estimated a harvest casualty rate of ten mice per hectare. Then, he multiplied that figure by 120 million hectares of farmland in the U.S.; meaning that 1.2 billion mice would die each year in food production if America became a wholly vegan country. Next, he estimated the number of animals that would be killed if half of our fields were dedicated to raising grass eating forage animals (cows, calves, sheep, lambs, etc.) from which to obtain meat. He found that there would Be 300,000 fewer animal deaths (.9 billion) annually from such an omnivorous diet than the number of deaths (1.2 billion mice) that would be caused from a universal vegan diet.

We are not obligated to do any such thing, of course. But I think Davis’s somewhat tongue-in-cheek study made an important point: Contending that meat eating is somehow murder while veganism is morally pristine because it doesn’t result in intentional animal deaths is factually false and self-delusional. No matter your diet, animals surely died that you might live.

However, my feeling is that we should be finding ways to be locavores, especially as concerns meat consumption, as Jill Richardson points out. But even getting locally grown vegetables is a very good thing.

Grown-up P.E. class has adults reliving childhood

From PhysOrg:

Grown-up P.E. class has adults reliving childhood

By HOLLY RAMER , Associated Press Writer, Medicine & Health / Other(AP) -- When "spastic ball" starts, it's better to duck first and ask questions later. This is Old School P.E., a two-hour exercise program strictly for adults, built around grown-up versions of gym class staples. Participants say getting in shape is a bonus to the main attraction - a Friday night out with friends, away from the kids. Mike Batista, center, stretches amongst other members of the Old School PE class at the recreation center in Newport, N.H., Friday, July 11, 2008. Strictly for adults, Old School P.E. is a two-hour exercise program built around grown-up versions of playground and gym class staples. (AP Photo/Cheryl Senter)

Mike Batista, center, stretches amongst other members of the Old School PE class at the recreation center in Newport, N.H., Friday, July 11, 2008. Strictly for adults, Old School P.E. is a two-hour exercise program built around grown-up versions of playground and gym class staples. (AP Photo/Cheryl Senter)

"From the very beginning, we decided on a very small set of rules because we didn't want it to get that 'league' kind of feel," said co-founder Mike Pettinicchio. "You want to go out, have some fun, be a little competitive, but we all have lives. There are not going to be any scouts in the stands."

In fact, there aren't any stands or bleachers in the Newport Recreation Center, just a narrow bench inches from the action. So when a game of floor hockey or spastic ball (think soccer mixed with basketball) gets going, spectators must stand ready to jump out of the way of a flying stick or ball.

The rules are simple: Spouses or significant others must play on opposing teams. Keeping score is prohibited. The commissioner - a new one is chosen each night - decides which games are played and can alter them as he or she sees fit. Want to play floor hockey with a dodgeball? Go for it. Two balls? The more the merrier.

Following on the success of grown-up dodgeball and kickball leagues, classes like Newport's Old School P.E. or Urban Recess in Portland, Ore., are a way to enjoy childhood activities without all the rules.

Newport Recreation director P.J. Lovely, who has been asked to speak about the program at a state conference for recreation officials, says he often has to turn people away when a new eight-week session starts because the gym is too small to accommodate more than about two dozen.

"We're almost a victim of our own success right now," he said.

During the most recent gathering, participants started with quick warm up session (four sit-ups, three push-ups, two jumping jacks) followed by three games: floor hockey, spastic ball and Ultimate Frisbee. They moved outside for the last activity, stretching out across the picturesque town common for a men vs. women competition.

"It's a way to keep a little bit active, because that's always hard to fit into our schedules as full-time parents and full-time workers," said Deb Gardner of Croydon. But she also appreciates the chance to meet new people in a welcoming environment.

"It's not really competitive," she said. "The guys will act kind of serious, but we really just joke and have a good time all night and pick on each other and laugh."

Ethel Frese, a professor of physical therapy at Saint Louis University and board certified cardiovascular and pulmonary specialist, said Old School P.E. fits into a trend toward fitness programs that move beyond the traditional bike or treadmill by emphasizing entertainment.

"The nice thing about doing a group activity is that you get the social interaction, which is also part of general health," she said, noting research that shows people with lots of friends and strong social networks living longer. "I do think there is a huge social benefit of exercise."

While certain activities might be better for strengthening or cardiovascular health, any activity that gets people moving is good, Frese said. And the variety offered by different games keeps the workout from getting stale, she said.

Karin Schmidt has seen that first hand in the Urban Recess fitness classes she runs in Portland. Activities like relay races, tag or even duck-duck-goose all are forms of efficient interval training that allow participants to stay within a target heart rate throughout their entire workout, she said.

"You get sort of distracted from the fact that you're actually working out," she said. "And I've seen some women get pretty ripped in six weeks."

Her program was coed when she started it in 2002, but she quickly restricted it to women-only because the guys "couldn't contain themselves."

"Girls were getting their eyes poked out or boobs grabbed because the guys were so competitive about it," she said.

She came up with the idea while talking to a fellow personal trainer about why some clients had trouble sticking to an exercise program: "We said, 'Well, you didn't have to twist a kid's arm to play at recess, why can't we do that as adults?'"

At Old School P.E., there are some concessions made for age, says Pettinicchio, who vetoed one commissioner's plan to play Red Rover because "we felt pulling shoulders out of bodies at 35 or 40 years of age is not a good thing."

He also offers a warning to newcomers.

"One of the things we try to stress is, it's probably been 15 to 20 years since you stepped on a gym floor," he said. "Saturday is probably going to be OK, but Sunday may be very difficult. Some people can't get out of bed until Monday."

Brain Science Podcast #42: “On Being Certain”

Brain Science Podcast #42: “On Being Certain”

Posted on July 25th, 2008 by docartemisEpisode 42 of the Brain Science Podcast is a discussion of On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You’re Not by Robert Burton, MD. This part 1 of a two part discussion of the unconscious origins of what Dr. Burton calls “the feeling of knowing.” In Episode 43 I will interview Dr. Burton. Today’s episode provides an overview of Dr. Burton’s key ideas.

In past episodes I have discussed the role of unconscious decision-making. On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You’re Not by Robert Burton, MD takes this topic to a new level. First, Dr. Burton discusses the evidence that the “feeling of knowing” arises from parts of our brain that we can neither access or control. Then he discusses the implications of this finding, including the fact that it challenges long-held assumptions about the possibility of purely rational thought.

Steve Pavlina - The Purpose of Life

Steve Pavlina has posted a brief article on the Purpose of Life. I like what he has to say, for example:

The purpose of life is to increase your alignment with truth, love, and power.

You are here to:

- Discover and accept ever deeper truths.

- Learn to love more deeply and unconditionally.

- Develop and express your creativity.

#1 leads to wisdom.

#2 leads to joy.

#3 leads to strength.

The point of life is to learn to be wise, joyful, and strong — all at the same time and without compromising or sacrificing any of these. In order to improve one, you must improve all three.

Yep.

Go read the rest.

Tags: Steve Pavlina, The Purpose of Life, personal growth, life, self exploration, truth, love, power, wisdom, joy, strength

Thursday, July 24, 2008

Meditation Slows AIDS Progression

Via Reuters:

Meditation slows AIDS progression: study

Thu Jul 24, 2008By Maggie Fox, Health and Science Editor

WASHINGTON (Reuters) - Meditation may slow the worsening of AIDS in just a few weeks, perhaps by affecting the immune system, U.S. researchers reported on Thursday.

If the findings are borne out in larger studies, it could offer a cheap and pleasant way to help people battle the incurable and often fatal condition, the team at the University of California Los Angeles said.

They tested a stress-lowering program called mindfulness meditation, defined as practicing an open and receptive awareness of the present moment, avoiding thinking of the past or worrying about the future.

The more often the volunteers meditated, the higher their CD4 T-cell counts -- a standard measure of how well the immune system is fighting the AIDS virus. The CD4 counts were measured before and after the two-month program.

"This study provides the first indication that mindfulness meditation stress-management training can have a direct impact on slowing HIV disease progression," David Creswell, who led the study, said in a statement.

His team tested 67 HIV-positive adults from the Los Angeles area, 48 of whom did some or all of the meditation. Most were likely to have highly stressful lives, Creswell said.

"The average participant in the study was male, African American, homosexual, unemployed and not on ARV (antiretroviral) medication," they wrote in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity.

The meditation classes included eight weekly two-hour sessions, a day-long retreat and daily home practice. "The people that were in this class really responded and just really enjoyed the program," Creswell said."The mindfulness program is a group-based and low-cost treatment, and if this initial finding is replicated in larger samples, it's possible that such training can be used as a powerful complementary treatment for HIV disease, alongside medications," he added.

QUALITY OF LIFE

About 30 percent of the volunteers were taking HIV drug cocktails, which can help suppress the virus.

"Even when we controlled for ARV use, we still saw these effects. Whether you are on or off the drugs you are going to see these benefits," Creswell said in a telephone interview.

Creswell said it was unclear how the stress-reducing effects of meditation work. It may directly boost CD4 T-cell levels, or suppress the virus, he said.

"We know that stress has direct effects on viral load," he said.

Creswell said he believes the program can help people infected with a variety of viruses and from all walks of life. HIV patients are especially highly stressed, he noted.

"These marginalized folks typically are experiencing the highest stress levels," he said.

But middle-class workers also experience stress. "Most people do report a lot of daily stress," Creswell said.And for AIDS patients, HIV drug cocktails are known to have a variety of side effects, from weight gain to nausea.

"One of the main side-effects of this particular treatment was an increase in their quality of life," Creswell said.

One Peace - Share the Silence

One Peace - Share the SilenceHere is Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne speaking at Schoolcraft College, Livonia, MI (October 2007):We invite you to join us.

>Thousands of people are expected to gather in Detroit metro area. Celebrate the international day of peace.One Peace is a multi-ethnic, large scale meditation and dialogue to be held September 21, the United Nations International Day of Peace. Held at the Eastern Michigan Convocation Center in Ypsilante, the event is expected to attract up to 10,000 people from the Detroit metropolitan area and across the country. It will be hosted by an interfaith, non-partisan coalition of local, regional and nationwide organizations in collaboration with Sarvodaya USA.

Primary speakers will be Gandhi Peace Prize winner Dr. A.T. Ariyaratne, founder of the Sarvodaya Movement of Sri Lanka, and Dr. Michael Bernard Beckwith of the 8,000-member Agape International Spiritual Center in Culver City, California. Representatives from diverse religious and ethnic communities in Michigan will share the stage.

One Peace is but one of an expected minimum of 3,500 such events in 200 countries worldwide on September 21. Its purpose is to focus positive spiritual energy and commitment to the cause of peace in individuals, families, communities, countries and the world. Participants will be asked to become conscious of basic human needs that are the precursors to peace, and commit themselves to a better world. For more information: www.onepeace.us

Founder of What Is Enlightenment? Magazine, Andrew Cohen asks the founder of Agape spiritual community Michael Beckwith and his musical director Rickie Byars Beckwith "What Is Soul?":

Do Economists Need Brains?

Neuroeconomics combines neuroscience, economics, and psychology to study how people make decisions. It looks at the role of the brain when we evaluate decisions, categorize risks and rewards, and interact with each other.And so the magazine takes a look at the growth and direction of emerging this field. For those already familiar with this stuff, there's not a lot of new info, but it's a well-written introduction for those new to the field.

Do economists need brains?Jul 24th 2008 | NEW YORK

From The Economist print editionA new school of economists is controversially turning to neuroscience to improve the dismal science

FOR all the undoubted wit of their neuroscience-inspired concept album, “Heavy Mental”—songs include “Mind-Body Problem” and “All in a Nut”—The Amygdaloids are unlikely to loom large in the annals of rock and roll. Yet when the history of economics is finally written, Joseph LeDoux, the New York band’s singer-guitarist, may deserve at least a footnote. In 1996 Mr LeDoux, who by day is a professor of neuroscience at New York University, published a book, “The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life”, that helped to inspire what is today one of the liveliest and most controversial areas of economic research: neuroeconomics.

In the late 1990s a generation of academic economists had their eyes opened by Mr LeDoux’s and other accounts of how studies of the brain using recently developed techniques such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed that different bits of the old grey matter are associated with different sorts of emotional and decision-making activity. The amygdalas are an example. Neuroscientists have shown that these almond-shaped clusters of neurons deep inside the medial temporal lobes play a key role in the formation of emotional responses such as fear.

These new neuroeconomists saw that it might be possible to move economics away from its simplified model of rational, self-interested, utility-maximising decision-making. Instead of hypothesising about Homo economicus, they could base their research on what actually goes on inside the head of Homo sapiens.

The dismal science had already been edging in that direction thanks to behavioural economics. Since the 1980s researchers in this branch of the discipline had used insights from psychology to develop more “realistic” models of individual decision-making, in which people often did things that were not in their best interests. But neuroeconomics had the potential, some believed, to go further and to embed economics in the chemical processes taking place in the brain.

Early successes for neuroeconomists came from using neuroscience to shed light on some of the apparent flaws in H. economicus noted by the behaviouralists. One much-cited example is the “ultimatum game”, in which one player proposes a division of a sum of money between himself and a second player. The other player must either accept or reject the offer. If he rejects it, neither gets a penny.According to standard economic theory, as long as the first player offers the second any money at all, his proposal will be accepted, because the second player prefers something to nothing. In experiments, however, behavioural economists found that the second player often turned down low offers—perhaps, they suggested, to punish the first player for proposing an unfair split.

Neuroeconomists have tried to explain this seemingly irrational behaviour by using an “active MRI”. In MRIs used in medicine the patient simply lies still during the procedure; in active MRIs, participants are expected to answer economic questions while blood flows in the brain are scrutinised to see where activity is going on while decisions are made. They found that rejecting a low offer in the ultimatum game tended to be associated with high levels of activity in the dorsal stratium, a part of the brain that neuroscience suggests is involved in reward and punishment decisions, providing some support to the behavioural theories.

As well as the ultimatum game, neuroeconomists have focused on such issues as people’s reasons for trusting one another, apparently irrational risk-taking, the relative valuation of short- and long-term costs and benefits, altruistic or charitable behaviour, and addiction. Releases of dopamine, the brain’s pleasure chemical, may indicate economic utility or value, they say. There is also growing interest in new evidence from neuroscience that tentatively suggests that two conditions of the brain compete in decision-making: a cold, objective state and a hot, emotional state in which the ability to make sensible trade-offs disappears. The potential interactions between these two brain states are ideal subjects for economic modelling.

Illustration by OttoAlready, neuroeconomics is giving many economists a dopamine rush. For example, Colin Camerer of the California Institute of Technology, a leading centre of research in neuroeconomics, believes that incorporating insights from neuroscience could transform economics, by providing a much better understanding of everything from people’s reactions to advertising to decisions to go on strike.

At the same time, Mr Camerer thinks economics has the potential to improve neuroscience, for instance by introducing neuroscientists to sophisticated game theory. “The neuroscientist’s idea of a game is rock, paper, scissors, which is zero-sum, whereas economists have focused on strategic games that produce gains through collaboration.” Herbert Gintis of the Sante Fe Institute has even higher hopes that breakthroughs in neuroscience will help bring about the integration of all the behavioural sciences—economics, psychology, anthropology, sociology, political science and biology relating to human and animal behaviour—around a common, brain-based model of how people take decisions.

Read the rest of this article.

Before I add some thoughts, I want to point out that the article raises the standard objection to fMRI studies, namely that these scans are too genreralized to be useful:

A standard MRI identifies activity in too large a section of the brain to support much more than loose correlations. “Blood flow is an indirect measure of what goes on in the head, a blunt instrument,” concedes Kevin McCabe, a neuroeconomist at George Mason University. Increasingly, neuroscientists are looking for clearer answers by analysing individual neurons, which is possible only with invasive techniques—such as sticking a needle into the brain. For economists, this “involves risks that clearly outweigh the benefits,” admits Mr McCabe. Most invasive brain research is carried out on rats and monkeys which, though they have similar dopamine-based incentive systems, lack the decision-making sophistication of most humans.

OK, my thoughts on this stuff.

I'd like to see this research expand in different directions. For example, does living in a capitalist society alter the brain in a specific way, as compared, for example, to those who grow up and live in communist societies, or socialist societies, or largely Third World economies based in working the fields or other subsistence living.

It would be interesting to see if social structures and cultural practices influence the brains of those who live in specific environments. My guess would be that it does, but who knows in what ways.

For example, in the "ultimatum game," would a North Korean or a Chinese person respond differently to the divisin of money than Americans do. Or for that matter, how would an Australian aboriginal respond, or an tirbal person from the Amazonian rain forests?

These are the kinds of questions that interest me. Unfortunately, a lot of this research (at least right now) is being conducted by marketing folks from major commodity producers (figuring out better ways to sell us stuff we don't need).

Children Educate Themselves II: We All Know That’s True for Little Kids

Part one is here: Children Educate Themselves I: Outline of Some of the Evidence.

This is not the whole article, I've only posted a little bit of each subject section -- to see the rest, follow the link at the bottom of this post.

Go read the whole post at Gray's blog.Children Educate Themselves II: We All Know That’s True for Little Kids

By Peter Gray on July 23, 2008 in Freedom to Learn

Have you ever stopped to think about how much children learn in their first few years of life, before they start school, before anyone tries in any systematic way to teach them anything? Their learning comes naturally; it results from their instincts to play, explore, and observe others around them. But to say that it comes naturally is not to say that it comes effortlessly. Infants and young children put enormous energy into their learning. Their capacities for sustained attention, for physical and mental effort, and for overcoming frustrations and barriers are extraordinary. Next time you are in viewing range of a child under the age of about five years old, sit back and watch for awhile. Try to imagine what is going on in the child's mind each moment in his or her interactions with the world. If you allow yourself that luxury, you are in for a treat. The experience might lead you to think about education in a whole new light--a light that shines from within the child rather than on the child.

Here I will sketch out a tiny bit of what developmental psychologists have learned about young children's learning. To help relate this knowledge to thoughts about education, I'll organize the sketch into categories of physical, linguistic, scientific, and social-moral education.

Physical Education

Lets begin with learning to walk. Walking on two legs is a species-typical trait of human beings. In some sense we are born for it. But even so it doesn't come easily. Every human being who comes into the world puts enormous effort into learning to walk.

***Language Education

If you have ever tried to learn a new language as an adult, you know how difficult it is. There are thousands of words to learn and countless grammatical rules. Yet children more or less master their native language by the age of four. By that age, in conversations, they exhibit a sophisticated knowledge of word meanings and grammatical rules. In fact, children growing up in bilingual homes acquire two languages by the age of four and somehow manage to keep them distinct.

***Science Education

***

Young children are enormously curious about all aspects of the world around them. Even within their first few days of life, infants spend more time looking at new objects than at those they have seen before. By the age at which they have enough eye-hand coordination to reach out and manipulate objects, they do just that--constantly. Six-month-olds examine every new object they can reach, in ways that are well designed to learn about it's physical properties. They squeeze it, pass it from hand to hand, look at it from all sides, shake it, drop it, watch to see what happens; and whenever something interesting happens they try to repeat it, as if to prove that it wasn't a fluke. Watch a six-month-old in action and see a scientist.

Social and Moral Education

Even more fascinating to young children than the physical environment is the social environment. Children are naturally drawn to others, especially to those others who are a little older than themselves and a little more competent. They want to do what those others do. They also want to play with others. Social play is the primary natural means of every child's social and moral education.

***

What Happens to Motivation at Age Five or Six?

Once, when my son was about seven years old and in public school, I mentioned to his teacher that he seemed to have been far more interested in learning before he started school than he was now. Her response was something like this: "Well, I'm sure you know, as a psychologist, that this is a natural developmental change. Children by nature are spontaneous learners when they are little, but then they become more task oriented."

I can understand where she got that idea. I've seen developmental psychology textbooks that divide the units according to age and refer to the preschool years as "the play years." All the discussion of play occurs in those first chapters. It is as if play stops at age five or six. The remaining chapters largely have to do with studies of how children perform on tasks that adults give them to perform. I imagine that the teacher had read such a book when she was taking education courses. But such books present a distorted view of what is natural. In the next two installments I will present evidence that when young people beyond the age of five or six are permitted the freedom and opportunities to follow their own interests, their drives to play and explore continue to motivate them, as strongly as ever, toward ever more sophisticated forms of learning.

I agree totally with his premise. Much of my education has occurred outside of school, by me following my own curiosity about the world. But I am rather unique in how I managed to get through school -- most kids get beaten down by the system until they lose the natural curiosity and wonder that is an innate part of all people.

I look forward to what Gray has to say about this subject in future posts.

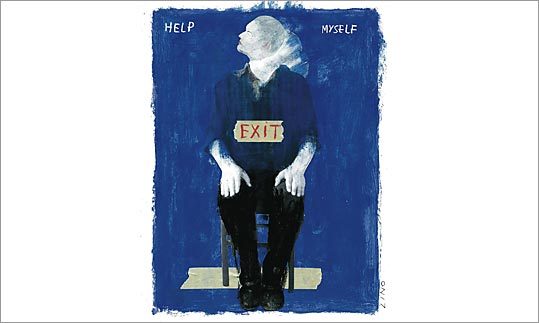

Suicide - On the Edge

The Boston Globe ran an interesting story the other day about the effort to pin down just when someone is suicidal or not. A tough task, especially give that the assessment tool (the IAT) is an imperfect thing. The article does raise questions of efficacy and is well-written and researched.

The Boston Globe ran an interesting story the other day about the effort to pin down just when someone is suicidal or not. A tough task, especially give that the assessment tool (the IAT) is an imperfect thing. The article does raise questions of efficacy and is well-written and researched.On the EdgeRead the rest of the article.

Can a test reveal if a person has a subconscious desire to kill himself? Peter Bebergal, who lost a brother to suicide, goes inside Mass. General, where Harvard researchers are trying to find out.

By Peter BebergalOn June 12, 2004, my brother Eric was admitted to the emergency room at Mass. General Hospital, unconscious after what appeared to be a failed suicide attempt. His wife, Cheryl, had found him passed out near the floor of their bedroom closet, a wire wrapped around his neck and attached to the closet pole. Had she gotten home any later, he might not have been alive. I arrived at the hospital a few hours after he had been brought in, joining Cheryl and my oldest sister, Lisa. The police interviewed us, and we all agreed that the past few months had been tumultuous: fights, restraining orders, drinking, and severe depression. Eric was kept in intensive care and, according to the police report, was in "stable and improving condition." He was released the next day.

A few weeks later, after Eric had agreed to go into an outpatient program but failed to show up for any appointments, he was found in his Winthrop apartment, slouched over on his knees. He had choked himself to death with a wire attached to a closet pole. He was 46.

As most clinicians would agree, one of the most heartbreaking aspects of psychiatric emergency work is the suicidal patient. When assessing a person's risk for suicide, ER doctors have little to work with. Unless the patient has a medical history that includes other suicide attempts, clinicians rely heavily on their evaluative skills and what is called the self-report, the patient's own appraisal of what happened and how the person is feeling. Was the overdose accidental or intentional? Had he or she been drinking? Did the person stop taking any prescribed medication? Did he really want to die when he strung up a wire in the closet and wrapped it around his neck, or was that a cry for help?

Eric's self-report became an important factor in deciding what to do. But my brother had worked in healthcare for many years and had a sense of what to say and how to act. What he wanted was to go home. But should he have been admitted involuntarily to the inpatient psychiatric unit instead? Weren't the circumstances of what brought him into the hospital in the first place reason enough to suspect he was seriously ill?

In Massachusetts, if a patient clearly demonstrates imminent risk, he can be involuntarily admitted for up to four days, at which point a court hearing determines whether to extend the stay. But those admissions are rare. Lanny Berman, executive director of the American Association of Suicidology, explains that unless you are actually threatening to kill yourself while in the hospital, it is highly unlikely that you will be admitted for any length of time. This is mainly because it is extremely difficult to assess suicidality in patients. For one thing, many people who are suicidal have good reason not to let on that they are a danger to themselves: They want to die.

What clinicians need is some other measure beyond external evidence that could assess whether someone like Eric is capable of suicide in the near future. Four years after my brother's death, Harvard researchers at MGH are experimenting with a test they think could help clinicians determine just that. It focuses on a patient's subconscious thoughts, and if it can be perfected, these researchers say it could give hospitals more of a legal basis for admitting suicidal patients.

Of course, I can't help thinking about whether such a test could have saved my brother. But I also wonder: Would it have been ethically right - or even possible - to save him even if he didn't want to save himself?

THIS MISSING PIECE in the suicidal puzzle is what prompted the innovative research study now in its final phase at MGH. The study, led by Dr. Matthew Nock, an associate professor in the psychology department at Harvard University, is called the Suicide Implicit Association Test. It's a variation of the Implicit Association Test, or IAT, which was invented by Anthony Greenwald at the University of Washington and "co-developed" by Dr. Mahzarin Banaji, now a psychology professor at Harvard who works a few floors above Nock on campus. The premise is that test takers, by associating positive and negative words with certain images (or words) - for example, connecting the word "wonderful" with a grouping that contains the word "good" and a picture of a EuropeanAmerican - reveal their unconscious, or implicit, thoughts. The critical factor in the test is not the associations themselves, but the relative speed at which those connections are made. (If you're curious, take a sample IAT test online at implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/.)

The IAT itself is not new - it was created in 1998 - and has been used to evaluate unconscious bias against African-Americans, Arabs, fat people, and Judaism. But critics question whether the test is actually practical, and up until now no one has tried to apply it to suicide prevention. As part of his training, Nock worked extensively with adolescent self-injurers - self-injury, such as cutting and burning, is an important coping method for those who engage in it, though they are often unlikely to acknowledge it. Nock thought that the IAT could serve as a behavioral measure of who is a self-injurer and whether such a person was in danger of continuing the behavior, even after treatment. In their first major study, Nock and Banaji asserted that the IAT could be adapted to show who was inclined to be self-injurious and who was not. And more important, they said, the test could reveal who was in danger of future self-injury.

The next step, Nock realized, was to use the test to determine, from a person's implicit thoughts, whether someone who had prior suicidal behavior was likely to continue to be suicidal. It would give doctors a third component, along with self-reporting and clinician reporting, and result in a more complete picture of a patient. Nock doesn't assume that a test like the IAT would be 100 percent accurate, but he believes it would have predictive ability. "It is not a lie detector," he says. "But in an ideal situation, a clinician who is struggling with a decision to admit a potentially suicidal patient to the hospital, or with an equally difficult decision to discharge a patient from the hospital following a potentially lethal suicide attempt, the IAT could provide additional information about whether the clinician should admit or keep that patient in the hospital."

Over two years, researchers at MGH asked patients who had attempted suicide if they would be willing to participate in the test. About two-thirds of them agreed (some 200 patients) - even though some had tried killing themselves just hours before - and after answering a battery of questions about their thoughts, sat with a laptop and took the IAT.

During one test, a person was shown two sets of words on a screen, one in the upper left corner, one in the upper right. A single word then appeared in the center, and the test taker was asked to indicate with a keystroke the corner containing the word that connected to the center word. The corner sets were drawn from two groups of words (one group was "escape" and "stay," and another was "me" and "not me"). In one version, the sets were "escape/not me" and "stay/me," and the series of words that appeared in the center included, among others, "quit," "persist," "myself," and "them." The correct answers called for "quit" to be associated with the side that had "escape," for "myself" to be matched with the side that had "me," and so forth. In theory, a delay in answering on "quit," even if the person got it right, could reveal that he was associating the idea of "quit" with the idea of himself. The word sets varied depending on the test, and bias could emerge in a positive or negative way. For example, if the sets were "escape/me" and "stay/not me" and a person hesitated in correctly matching "myself" to the side with "me," it could reveal that he was associating himself with the idea of "stay."

For about the next five months, Nock and his research team at Harvard will analyze all the data collected from MGH. If they think their findings show promise, they will follow up and run their experiment again to see if it yields similar results. If it does, they may seek to implement the test at an area hospital. For now, following up with patients will be pivotal in assessing the test's effectiveness. Tragically, though, the only way researchers will know for sure whether the test can predict behavior is if a key number of patients attempt suicide again.

I have no doubt that the IAT can be a useful tool, but its limitations were pointed out in a study that I posted a few days ago about narcissists. Anyone with the slightest grasp on reality (and most suicidal people are not psychotic) can give answers that will jack the test and get them released, just as happened with the author's brother in this article.

On the other hand, if it saves just ONE life that otherwise would have been lost, then it should be used until some better assessment tool becomes available.

Still, the article goes on to raise some serious efficacy and ethics issues about the test:

The test also raises an ethical issue. Could the IAT have other, Big Brother-type uses that might give those in authority too much of a view into our thought-lives? For example, could something like the IAT be given to a prisoner before a parole board to assess whether he or she would be likely to commit another crime? Nock believes that if the test proves to be accurate, then yes, it would be appropriate to use when making certain determinations. In the case of suicidal patients, he says, if the test is 100 percent accurate, then it should weigh "very heavily" in deciding if someone should remain in the hospital. If it proves to be 75 percent accurate, he adds, then it should not override other evidence.

Dr. Leon Eisenberg, professor of social medicine and professor of psychiatry emeritus at Harvard, agrees that on the surface there is something troubling about the idea that what he calls the "last bastion of privacy" could be tampered with. But on the other hand, he sees the IAT as modest in its tinkering with unconscious thoughts. And he adds that "most doctors, most laws, and most policemen think preventing suicide is a legitimate state function."

Another issue is simply whether the test can actually be useful in the context of the emergency room. In the fit of a depressive episode or under the influence of drugs and alcohol, a person who might try to kill himself might otherwise not harbor suicidal thoughts. Nock says that suicidal thoughts and behaviors can be remarkably transient. In some cases, he says, a person might feel suicidal at one moment, but after a failed attempt is happy to still be alive and no longer wants to die. Nevertheless, Thomas Joiner, author of the 2005 book Why People Die by Suicide, believes that those who are most at risk are likely to tell a clinician they are suicidal. While he thinks the IAT could be an important evaluative tool, he wonders if using the test in what will already be a challenging clinical setting might be a distraction.

Nock agrees but points to a troubling statistic from a 2003 study: More than 70 percent of the people who died by suicide had said in their final communication to another person that they were not a danger to themselves. "We cannot rely on a person's self-report alone, as doing so will certainly lead us to miss many, many opportunities to prevent suicide deaths," he says. Nock wants only to be able to fill in the gaps of what is now a tricky part of psychiatric work. Still, for those who want to die, a test like the IAT will only further reveal what their private intent is. How then can clinicians and researchers go from test to treatment? How could knowing that my brother wanted to die the night he was released help experts show him his life could have meaning?

Go read the whole article.