This quote is from an article by Reggie Ray, "Touching Enlightenment," in

the Spring issue of Tricycle.

The body is open, the body is sensitive, the body is vulnerable, the body is intelligent, and the body is completely beyond judgment. From the body's viewpoint, whether we like or dislike what is occurring in the world is irrelevant. Whatever occurs in our environment, our body receives.

While the body receives experience in a completely open and nonjudgmental way, because of our investment in who we think we are and our efforts to maintain this self, we refuse to receive a great part of what the body knows and feels and understands, "we" meaning our conscious self, our conscious mind, our ego. An experience occurs on a somatic level, and we say "no," or we say, "I want this part of what happened but not that part," but we don't simply accept what the body knows in a straightforward way.

This is what Buddhism calls ignorance. Ignorance is not being unintelligent, uninformed, or deluded. Ignorance is actually incredibly intelligent. Ignorance means that we block out the wisdom and knowledge already abiding in our body that is inconsistent with who we think we are or are striving to be.

This leads to another most important question: what happens to all that denied and rejected experience that we are already holding in our bodies? Simply put, all that somatic awareness and experience is walled off from our consciousness. It abides in a no-man's land in our tissues, our muscles, our ligaments and tendons, our blood, our bones.

This leads to another most important question: what happens to all that denied and rejected experience that we are already holding in our bodies? Simply put, all that somatic awareness and experience is walled off from our consciousness. It abides in a no-man's land in our tissues, our muscles, our ligaments and tendons, our blood, our bones.

There is a lot that can be said about this, including a rejection of Ray's major premise as a violation of the pre-trans fallacy. In general, the body is thought to be pre-mental in its perceptions and experience.

Social psychologists have actually done studies that show the body is only capable of a few basic states (excitement, anxiety, depression, and so on), but that how we interpret those sensations based on the context (social, psychological, and so on) determines how we respond emotionally to the event.

That said, there is still some non-rational truth to what Ray is saying. So this is my response--an old poem from a darker time in my life.

what the body knows

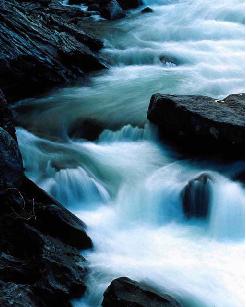

not blood, but some invisible viscous fluid flowing

from the darkest, fertile center, from

a temperate cave of bone within the body’s mystery,

beneath knowing, from this place, not blood,

but something other, seeps from these wounds,

a kind of emotional spring rising to surface

of skin, of awareness, marking the passage of time,

of loss, in slow, uneven currents

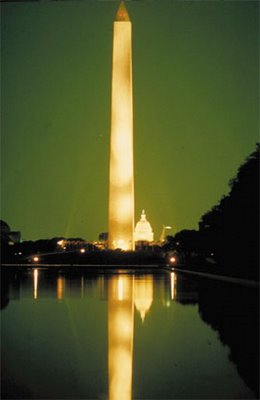

and yet, of these common wounds, always more

obvious at night, after some wine, unable

to sleep, again, of these wounds so little known,

pain of loss, yes, but little more is harvested

from this ripeness, from this rich soil where memory

is transfigured to bone, and perhaps,

even some blood in the meditation, unwavering

attention paid, any price to heal

so much more to know, to be tasted and savored,

the simple touch of tongue, gently,

to that wound, and when sleep finally arrives, quietly

converting voice to image, the body

knows what must be done, understands the taste

of what is not blood, yet flows beneath skin,

beneath awareness, understands the subtle alchemy

of loss, nourishing pact with what has passed